ABSTRACT

While most patients with diabetes have Type 1 diabetes (T1D) or Type 2 diabetes (T2D) there are other etiologies of diabetes that occur less frequently. In this chapter we will discuss a number of these less common causes of diabetes. It is clinically very important to recognize these uncommon causes of diabetes as treatment directed towards the underlying etiology can at times result in the remission of diabetes (for example Cushing’s Syndrome) or be required to avoid other complications of the underlying disorder (for example hemochromatosis, which in addition to causing diabetes can lead to severe liver disease and congestive heart failure). In this chapter the following disorders that are associated with diabetes are discussed: 1) genetic disorders of insulin action (Type A insulin resistance, Donohue Syndrome/Leprechaunism, Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome); 2) maternally inherited diabetes mellitus and deafness syndrome; 3) disorders of the exocrine pancreas (pancreatitis, trauma/pancreatectomy, neoplasia, cystic fibrosis, hemochromatosis); 4) endocrinopathies (acromegaly, Cushing’s syndrome, glucagonoma, pheochromocytoma, hyperthyroidism, somatostatinoma, primary hyperaldosteronism); 5) drug induced; 6) infections; 7) immune mediated (stiff-man syndrome, anti-insulin receptor antibodies); 8) ketosis prone diabetes (Flatbush diabetes); and 9) genetic disorders sometimes associated with diabetes (Down syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, Turner syndrome, Wilsons syndrome, Wolfram syndrome, Friedreich ataxia, Bardet-Biedl syndrome [Laurence-Moon-Biedl syndrome], myotonic dystrophy, Prader-Willi syndrome, Alström syndrome, and Werner syndrome). Gestational diabetes, monogenic diabetes (maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY) and neonatal diabetes), lipodystrophy, fibrocalculous pancreatic disease, diabetes associated with HIV infection, diabetes due to the autoimmune polyglandular syndromes, and post-transplant diabetes are not discussed in this chapter as they are discussed in other Endotext chapters.

INTRODUCTION

While most patients with diabetes have Type 1 diabetes (T1D) or Type 2 diabetes (T2D) there are other etiologies of diabetes that occur less frequently. In this chapter we will discuss a number of these less common causes of diabetes (see table 1). Note that gestational diabetes, monogenic diabetes (maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY) and neonatal diabetes), lipodystrophy, fibrocalculous pancreatic disease, malnutrition related diabetes (being written), diabetes associated with HIV infection, diabetes due to the autoimmune polyglandular syndromes, and post-transplant diabetes are discussed in separate Endotext chapters (1-7). It is clinically very important to recognize these uncommon causes of diabetes as treatment directed towards the underlying etiology can at times result in the remission of diabetes (for example Cushing’s Syndrome) or be required to avoid other complications of the underlying disorder (for example hemochromatosis, which in addition to causing diabetes can lead to severe liver disease and congestive heart failure). Additionally, recognizing the type of diabetes can allow for the appropriate treatment. For example, recognizing ketosis prone diabetes facilitates discontinuing insulin therapy.

|

Table 1. Non-Type 1 Non-T2D Classification

|

|

Genetic defects of beta-cell development and function

MODY (common causes- GCK, HNF1A, HNF4A, HNF1B)

Neonatal Diabetes (common causes- KCNJ11, ABCC8, INS, 6q24)

1. Mitochondrial DNA

|

|

Genetic defects in insulin action

1. Type A insulin resistance

2. Donohue Syndrome (Leprechaunism)

3. Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome

4. Lipoatrophic diabetes

|

|

Diseases of the exocrine pancreas

1. Pancreatitis

2. Fibrocalculous pancreatic disease

3. Trauma/pancreatectomy

4. Neoplasia

5. Cystic fibrosis

6. Hemochromatosis (iron overload)

Thalassemia (iron overload)

|

|

Endocrinopathies

1. Acromegaly

2. Cushing’s syndrome

3. Glucagonoma

4. Pheochromocytoma

5. Hyperthyroidism

6. Somatostatinoma

7. Primary hyperaldosteronism

|

|

Drug- or chemical-induced hyperglycemia

1. Vacor

2. Pentamidine

3. Nicotinic acid

4. Glucocorticoids

5. Diazoxide

6. Check point inhibitors

7. Phenytoin (Dilantin)

8. Interferon alpha

9. Immune suppressants

10. Others (statins, psychotropic drugs, b-Adrenergic agonists, thiazides, fluoroquinolones, beta-adrenergic drugs, teprotumumab, etc.)

|

|

Infections

1. Congenital rubella

2. Hepatitis C virus

3. HIV

COVID-19

|

|

Immune-mediated diabetes

1. Stiff-man syndrome

2. Anti-insulin receptor antibodies

3. Autoimmune polyglandular syndromes

|

|

Diabetes of unknown cause

1. Ketosis-prone diabetes (Flatbush diabetes)

|

|

Other genetic syndromes sometimes associated with diabetes

1. Down syndrome

2. Klinefelter syndrome

3. Turner syndrome

4. Wilsons syndrome

5. Wolfram syndrome

6. Friedreich ataxia

7. Bardet-Biedl syndrome (Laurence-Moon-Biedl syndrome)

8. Myotonic dystrophy

9. Prader-Willi syndrome

10. Alström syndrome

|

MATERNALLY INHERITED DIABETES MELLITUS AND DEAFNESS (MIDD)

Maternally inherited diabetes mellitus and deafness (MIDD) is a mitochondrial disorder characterized by diabetes and progressive sensorineural hearing loss (8-10). Mitochondrial DNA is only transmitted from the mother as the sperm lacks mitochondrial DNA (8). Therefore, over 50% of affected individuals with MIDD have a mother with diabetes. A mother with this disorder transmits the mutation to almost all of her offspring (11). However, the proportion of somatic cells with the mutation can vary considerably, a condition called heteroplasmy (9). The higher the number of somatic cells with a mutation the greater is the penetrance of symptoms and disease severity. Additionally, the proportion of somatic cells with a mutation can vary from tissue to tissue and may explain the variability in the manifestations of this disorder (9). The prevalence of mitochondrial diabetes in the diabetes population depends on ethnic background and ranges between 0.2% and 2%, with the highest prevalence in Japan (11).

MIDD is associated with a point mutation in a transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA) gene at position 3243 with an A to G transition (8-10). In addition to diabetes and auditory impairment, the m.3243A>G mutation can cause other clinical manifestations including central neurological and psychiatric disorders, eye disease, myopathy, cardiac disorders, renal disease, endocrine disease, and gastrointestinal disease (8,9). Other point mutations in mitochondrial DNA can also result in diabetes and deafness but these mutations are rare in comparison to m.3243A>G (8,9,11).

It is thought that defects in mitochondrial function result in the decreased production of ATP following glucose uptake by beta cells resulting in decreased insulin secretion in response to elevated glucose levels (8,9). Additionally, mitochondrial dysfunction in the highly metabolically active pancreatic islets ultimately results in the loss of B‐cell mass further compromising insulin secretion (9). Insulin sensitivity is usually normal (11). Other tissues that are metabolically active may also be adversely effected by the inability of the mitochondria to produce ATP including the cells in the cochlea (9).

The clinical syndrome of MIDD can phenotypically resemble either T1D or T2D (9,11). The age of onset varies between childhood and mid-adulthood. Approximately 20% of patients present acutely with high glucose levels and even ketoacidosis (9). Most patients do not have islet cell antibodies but they are present in a small number of patients (9). This could be due to concomitant T1D or to the development of antibodies secondary to beta cell destruction due to mitochondria dysfunction. Patients tend to be thin rather than obese (9). This disorder can be distinguished from MODY by the presence of multi-organ involvement, particularly sensorineural hearing loss, and maternal rather than autosomal dominant transmission. Initially patients may be treated with diet and/or oral agents but overtime most patients with MIDD progress to requiring insulin therapy (8,9,11).

As the name implies, this disorder is recognized by the presence of diabetes and deafness and a family history of these conditions in maternal relatives (9,11). Hearing loss is present in approximately 75% of patients and typically precedes the development of diabetes (9). Hearing loss is more common and severe in males (9). Approximately 10-15% of patients, in addition to having diabetes and deafness, also have the syndrome of mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke‐like episodes (9). The m.3243A>G mutation can cause a wide spectrum of abnormalities that include neurological abnormalities (strokes, dementia, seizures), psychiatric disorders including recurrent major depression, schizophrenia and a variety of phobias, macular retinal dystrophy with pigmentation, proximal myopathy, cardiomyopathy, renal failure, short stature, endocrine dysfunction, and gastrointestinal complaints (9). The finding of classical retinal dystrophy and hyperpigmentation on routine eye exam should suggest the diagnosis of maternally inherited diabetes mellitus and deafness. Once suspected the diagnosis of MIDD should be confirmed by genetic testing for the mitochondrial DNA point mutation at position 3243 (A>G). This is usually initially carried out on blood cells but if negative, urinary cells or skeletal muscle can be tested and if necessary one can test for other mutations that cause similar phenotypes (12). Once a diagnosis is confirmed first-degree family members at risk should be screened for the mutation and provided with genetic counseling. For those carrying the mutation without clinical manifestations, screening for diabetes and monitoring of kidney function, hearing, and cardiac function should be carried out.

GENETIC DEFECTS IN INSULIN ACTION

Overview of Insulin Receptor Defects

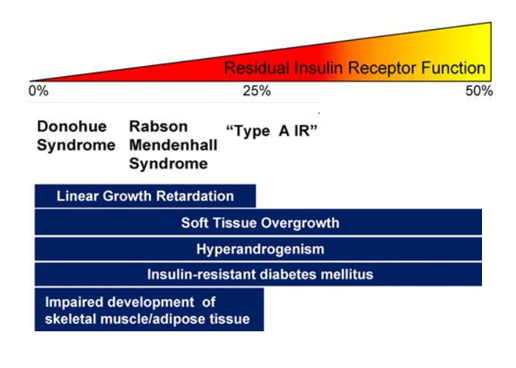

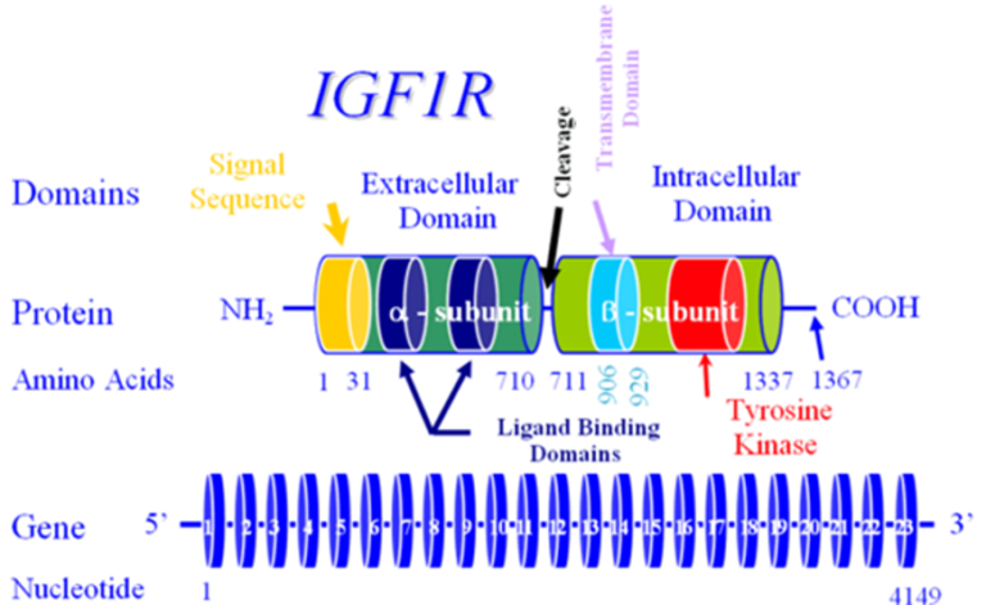

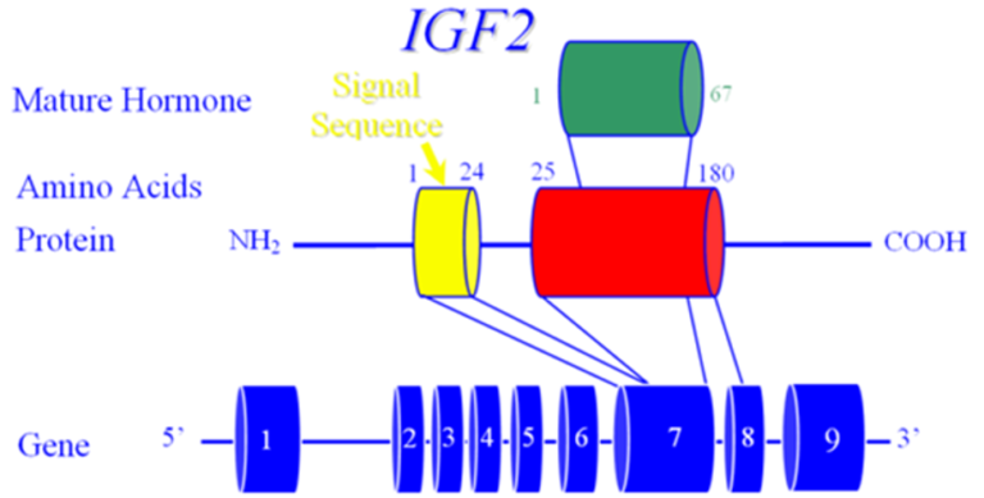

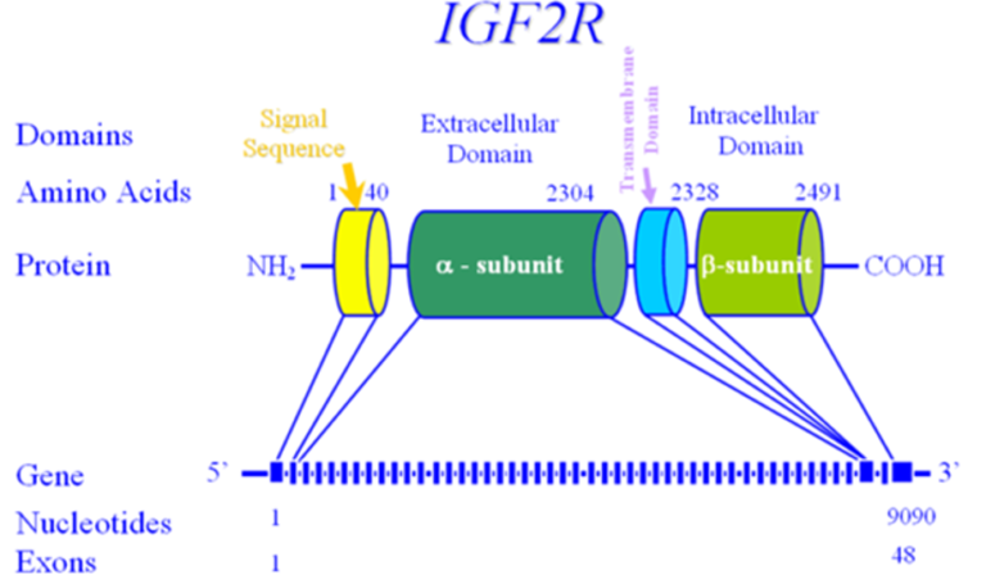

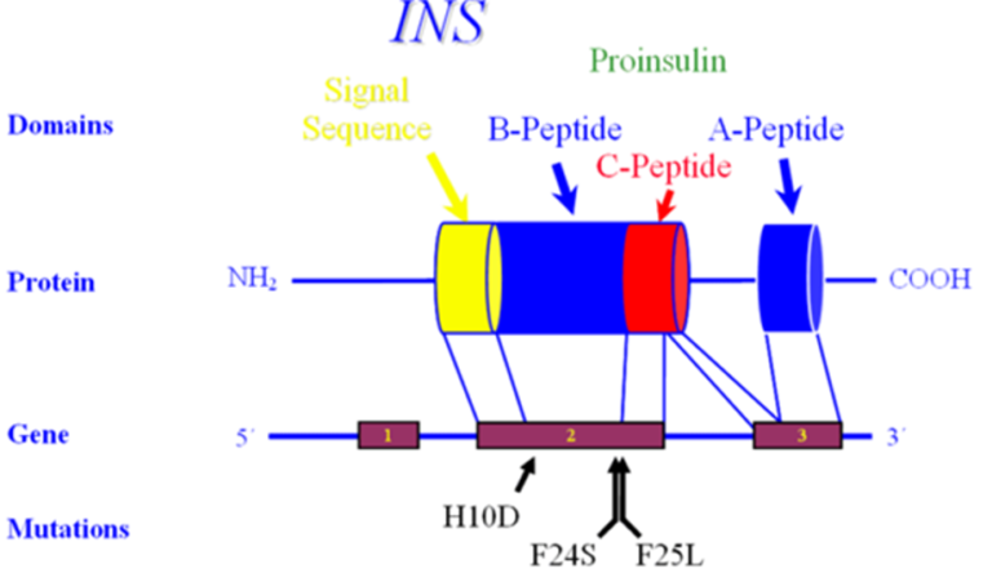

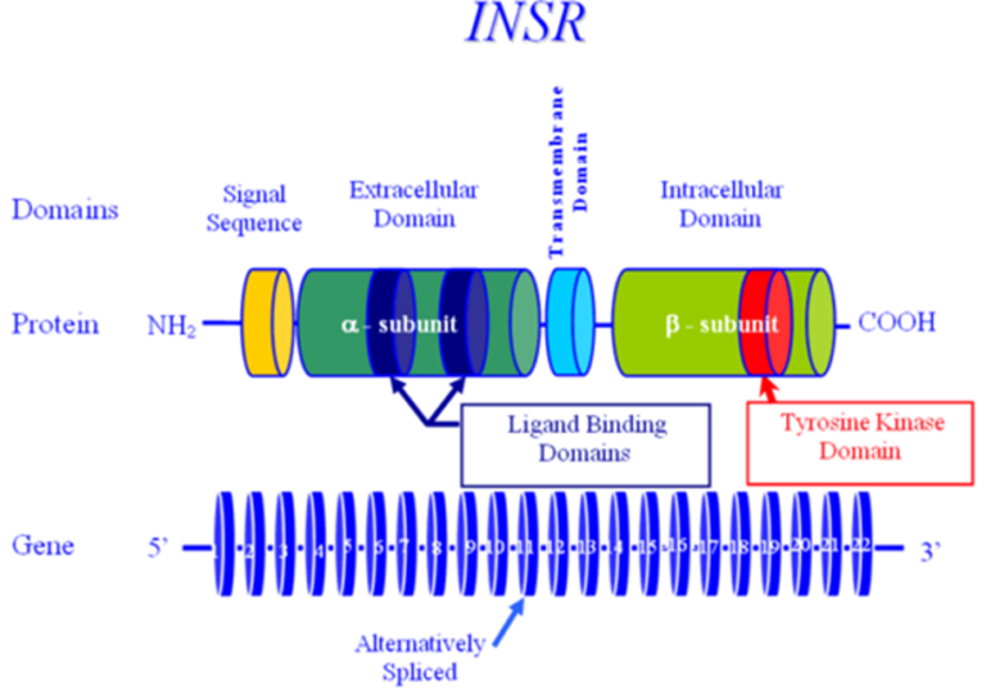

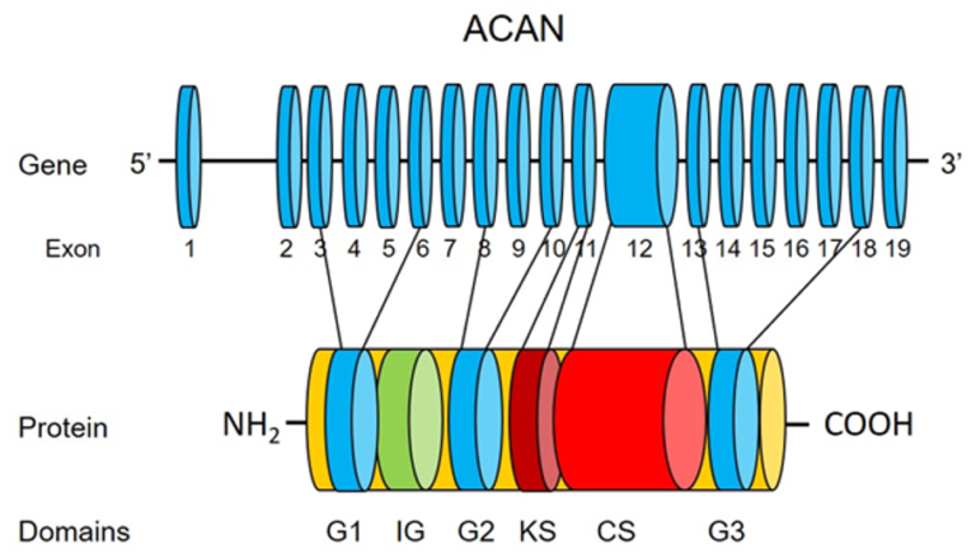

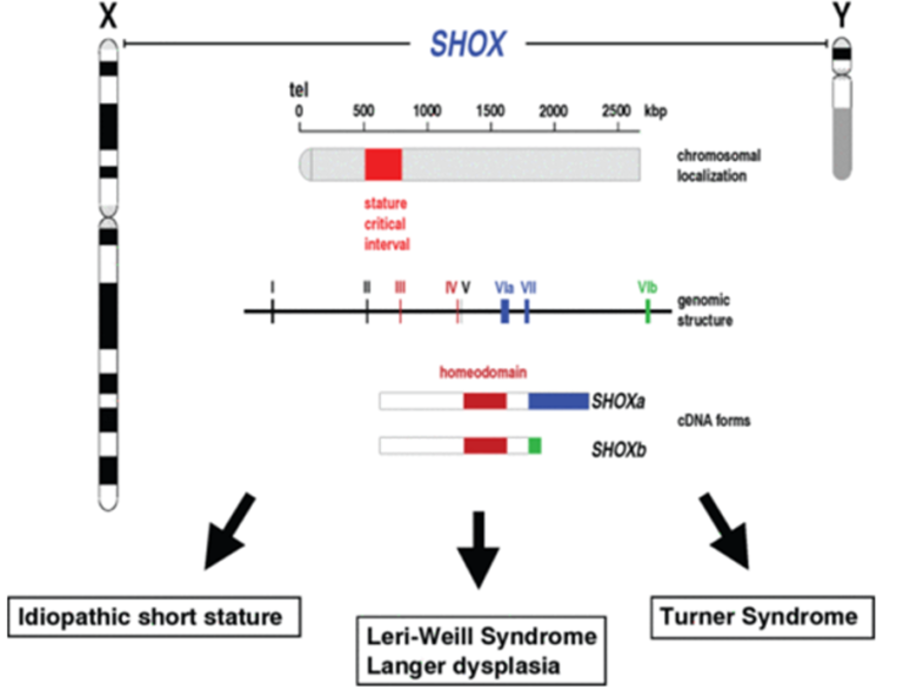

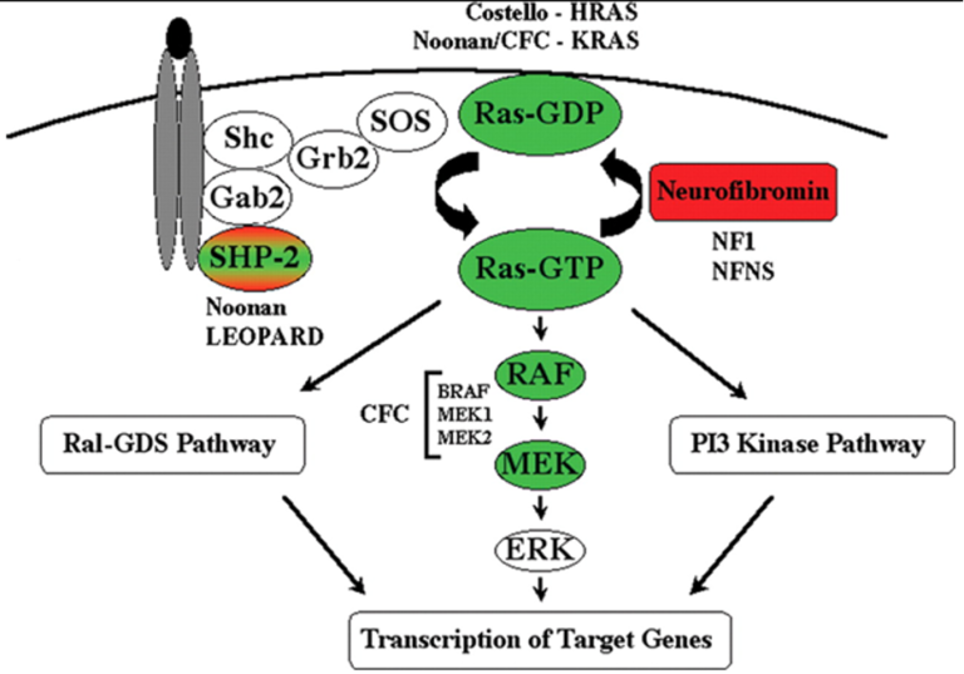

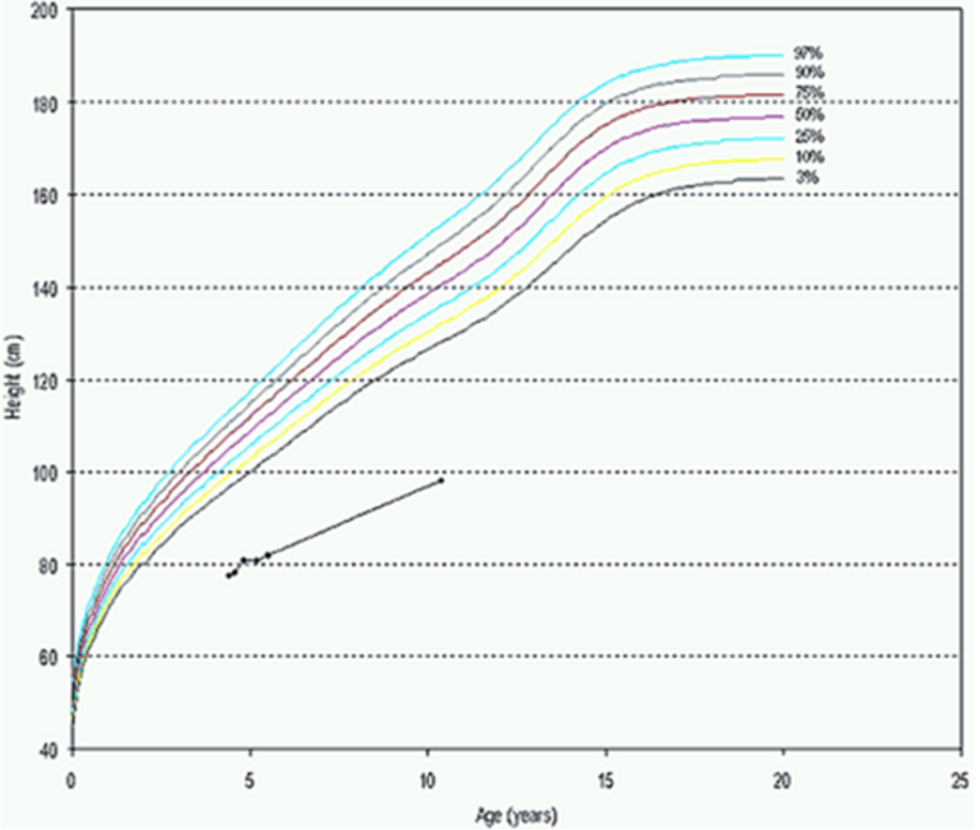

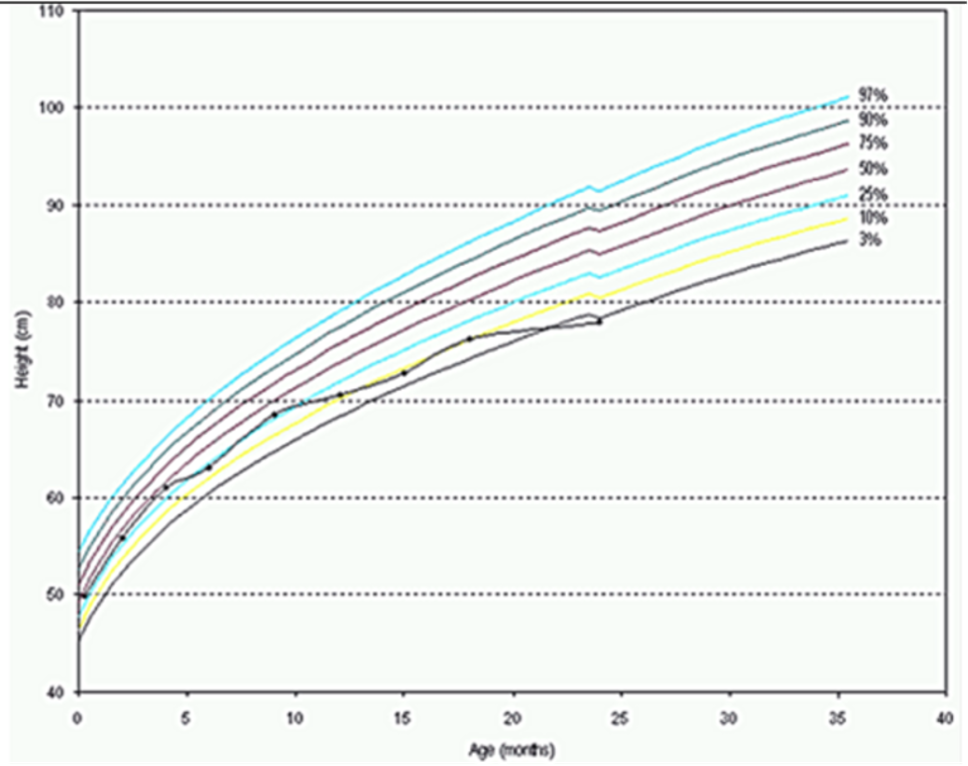

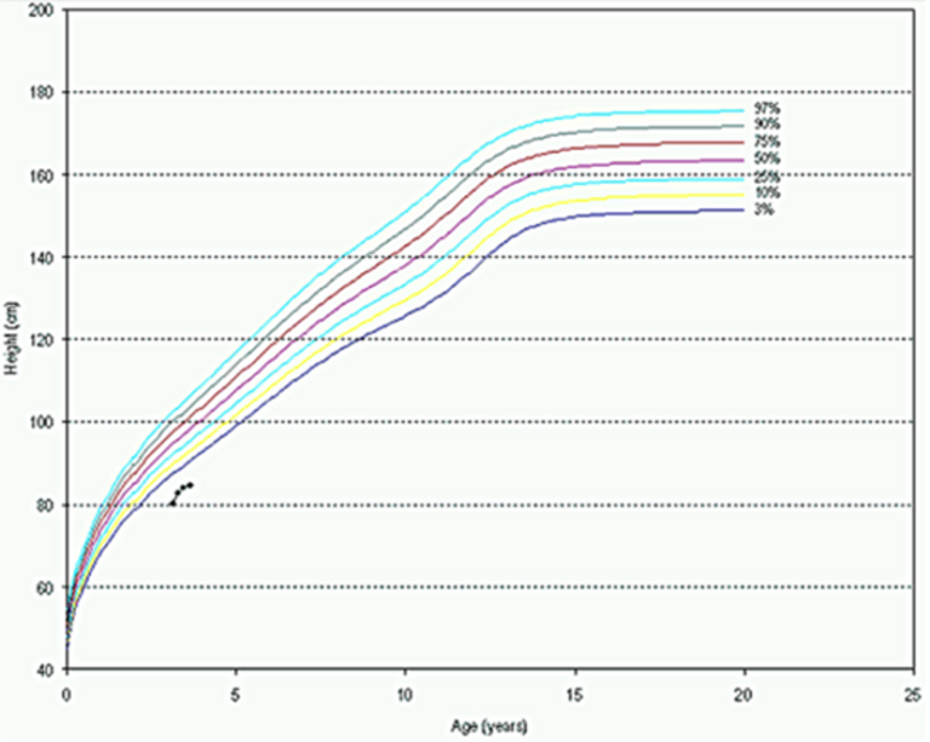

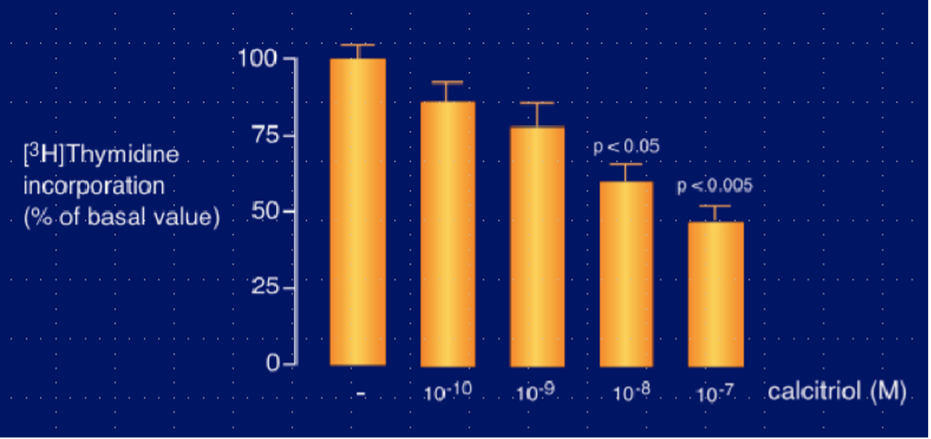

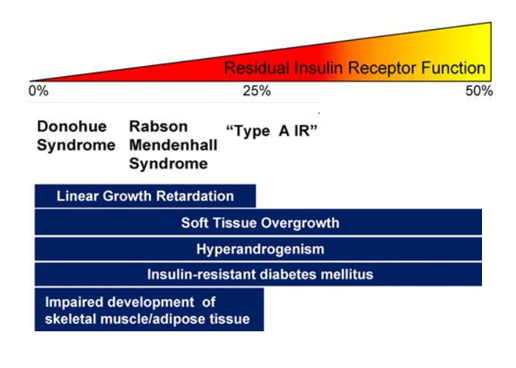

Mutations in the insulin receptor can cause different degrees of insulin resistance but do not need to be associated with diabetes per se (13). A large number of different mutations have been described and they can be classified as mutations that prevent synthesis of the receptor, inhibit transport of the receptor to the plasma membrane, decrease insulin binding to the receptor, impair transmembrane signaling, or increase receptor degradation (14). Pancreatic beta cell hyperplasia and hyperinsulinemia can compensate for the insulin resistance preventing hyperglycemia. Fasting hypoglycemia and postprandial hyperglycemia may be observed. Over time the beta cells’ ability to secrete insulin diminishes and frank diabetes usually develops. Treatment of the diabetes may require very high doses of insulin (15). Unfortunately, insulin sensitizers have not been very effective in patients with insulin receptor defects. In contrast to the typical patients with insulin resistance, obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and fatty liver are not usually present (15,16). Acanthosis nigricans, pigmentation in the neck or axillae, is a visible sign of severe insulin resistance (13,15). In females, severe insulin resistance is usually associated with hyperandrogenism, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, anovulation, hirsutism, acne, and masculinization (13,15). It is hypothesized that ovarian dysfunction and acanthosis nigricans are due to high levels of insulin acting via the IGF1 receptors (16). The amount of residual insulin receptor function determines the specific syndrome in patients with insulin receptor mutations (Figure 1).

Type A Insulin Resistance

This autosomal dominant disorder includes patients with severe insulin resistance and acanthosis nigricans (13,15). Patients have normal growth and females show ovarian hyperandrogenism that typically presents in the peripubertal period (15). In females, hyperglycemia develops after ovarian hyperandrogenism and acanthosis nigricans. Males display only acanthosis nigricans and they often remain undiagnosed even after the development of symptomatic diabetes, which may not occur until the patients are adults. These patients have mutations in the insulin receptor gene that decreases the activity of the insulin receptor (14,15). In addition, mutations in transcription factors that stimulate the expression of insulin receptors can lead to a similar phenotype as mutations in the insulin receptor (13,16). Inherited defects in pathways downstream of the insulin receptor can also lead to clinical abnormalities similar to mutations in the insulin receptor (13,16).

Donohue Syndrome (Leprechaunism)

Donohue syndrome is a rare congenital (1:1,000,000), autosomal recessive syndrome characterized by very severe insulin resistance due to mutations in the insulin receptor gene, dysmorphic features such as protuberant and low-set ears, flaring nostrils and thick lips, growth retardation, failure to thrive, and early death (14). The name leprechaunism relates to the elfin features of those affected. Clinical features include in addition to acanthosis nigricans, hypertrichosis, hirsutism, dysmorphic facies, breast enlargement, abdominal distension, and lipoatrophy. Patients have extremely high levels of insulin and can develop impaired glucose tolerance or overt diabetes. The prognosis for infants with this condition is very poor and most will die in the first year of life. When parents, who are heterozygous for mutations in the insulin receptor are studied, many of these individuals are insulin resistant (14).

Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome

The Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome represents another disorder of extreme insulin resistance (15). This autosomal recessive syndrome is associated with mutations in the insulin receptor gene (13). Initially fasting hypoglycemia, postprandial hyperglycemia, and marked hyperinsulinemia may be observed (13). When beta-cells decompensate, hyperglycemia may become very difficult to treat. Clinical features include in addition to acanthosis nigricans, phallic enlargement, precocious pseudopuberty, short stature, and abnormal teeth, hair, and nails (14,15). Hyperplasia of the pineal gland is an unusual feature (14). Prognosis is poor as diabetes is difficult to control even with high insulin doses (14). Hyperglycemia leads to microvascular disease and/or diabetic ketoacidosis resulting in death in the second and third decades of life (13). Leptin administration has resulted in an improvement in this syndrome (17,18).

DISEASES OF THE EXOCRINE PANCREAS

Diseases that destroy the pancreas can cause diabetes even in individuals who do not have risk factors for diabetes (19). In the medical literature this is often referred to as Type 3C diabetes. Acquired causes of damage to the pancreas include pancreatitis, trauma, infection, pancreatic carcinoma, and pancreatectomy. Inherited disorders that affect the endocrine pancreas, such as hemochromatosis, thalassemia, and cystic fibrosis, can also cause insulin deficiency and diabetes. The distribution of causes for diabetes secondary to pancreatic disorders in one study was chronic pancreatitis (79%), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (8%), hemochromatosis (7%), cystic fibrosis (4%), and previous pancreatic surgery (2%) (20). The prevalence of diabetes secondary to pancreatic disease is estimated to range from 1% to 9% and likely will depend on the patient population studied (21). In a population study carried out in New Zealand the prevalence of diabetes secondary to pancreatic disorders was close to that of T1D (22).

Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis may lead to the destruction of the beta cells due to inflammation and irreversible fibrotic damage (23). In addition to destroying the beta cells, pancreatitis also leads to the destruction of glucagon secreting alpha-cells and pancreatic polypeptide secreting cells (23). The decrease in insulin secretion is the primary mechanism leading to hyperglycemia. In addition, the decrease in secretion of pancreatic polypeptide leads to a decrease in hepatic insulin sensitivity resulting in increased hepatic glucose production (21,23,24). Nutrient malabsorption that occurs secondary to pancreatitis leads to impaired incretin secretion that can result in diminished insulin release by the remaining beta-cells (25). Acute pancreatitis can induce transient hyperglycemia (stress hyperglycemia) that can last for several weeks or permanent hyperglycemia (21,26,27). The risk of developing diabetes after acute pancreatitis is increased after severe pancreatitis, hypertriglyceridemia or alcohol as the etiology of pancreatitis, and the occurrence of pancreatic necrosis (28). Other predictors of the development of diabetes include obesity, a family history of diabetes, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, history of pancreatic surgery, pancreatic calcifications, and long duration of pancreatitis (29).

The prevalence of diabetes secondary to pancreatitis varies greatly with studies in North America estimating a prevalence of 0.5%-1.15% whereas in Southeast Asia, where tropical or fibrocalcific pancreatitis is endemic, a prevalence of approximately 15%-20% has been reported (23) (see chapter in Tropical Endocrinology Section of Endotext entitled “Fibrocalculous Pancreatic Diabetes” for an in depth discussion of this entity (7). Recently, data from the UK Royal College of General Practitioners Research and Surveillance Centre found 559 cases of diabetes following pancreatic disease in 31,789 cases of adults newly diagnosed with diabetes (1.8%) (30). Most cases of diabetes following pancreatic disease were classified as T2D (30). In another study approximately 50% of the patients with diabetes secondary to pancreatitis were not recognized and were incorrectly thought to have T2D. It is very likely that many cases of diabetes secondary to pancreatitis are not recognized to be due to pancreatic disease.

The prevalence of diabetes in patients with diagnosed pancreatitis has ranged between 26-80%, depending on the cohort and duration of follow up (21,23,31). The prevalence of diabetes increases with the duration of pancreatitis and early onset of calcific disease (23). Because of the high risk of diabetes in patients with pancreatitis these patients should be periodically screened for the presence of diabetes with measurement of fasting glucose and/or A1c levels.

At times it can be difficult to distinguish diabetes secondary to pancreatitis from T1D or T2D. The following diagnostic criteria have been proposed (Table 2) (23).

|

Table 2. Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Diabetes Secondary to Pancreatitis

|

|

Major Criteria (must be present)

|

|

Presence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (monoclonal fecal elastase-1 test or direct function tests)

Pathological pancreatic imaging (endoscopic ultrasound, MRI, CT)

Absence of T1D associated autoimmune markers

|

|

Minor Criteria

|

|

Absent pancreatic polypeptide secretion

Impaired incretin secretion (e.g., GLP-1)

No excessive insulin resistance (e.g., HOMA-IR)

Impaired beta cell function (e.g., HOMA-B, C-Peptide/glucose-ratio)

Low serum levels of lipid soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K)

|

It should be recognized that these proposed criteria have not been rigorously tested nor are all criteria available in routine clinical practice. In addition, there are a number of key considerations. First, long-standing T1D and T2D are associated with exocrine pancreatic failure (32). It has been estimated that 26% to 74% of patients with T1D and 28% to 36% of patients with T2D have evidence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (19). Second, patients with diabetes are at a higher risk for developing acute and/or chronic pancreatitis (33). Lastly, patients with previous episodes of pancreatitis may also develop T1D or T2D independently of their exocrine pancreatic disease. When diabetes occurs in patients with a pre-existing diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis it is likely that pancreatitis is an important contributor to the development of diabetes.

Testing for T1D associated autoimmune markers can be helpful in separating T1D from diabetes secondary to pancreatic disease. The presence of islet cell antibodies supports the diagnosis of T1D. The pancreatic polypeptide response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia, secretin-infusion, or a mixed nutrient ingestion can be helpful in separating T2D from diabetes secondary to pancreatic disease. Patients with diabetes secondary to pancreatitis have an absent or reduced pancreatic polypeptide response while patients with T2D have an elevated pancreatic polypeptide response (23,31). Studies have shown that pancreatic polypeptide regulates hepatic insulin sensitivity and the absence of pancreatic polypeptide leads to hepatic insulin resistance and enhances hepatic glucose production, which could contribute to the abnormal glucose metabolism that occurs with pancreatic disease (21).

In patients with diabetes secondary to pancreatitis hyperglycemia can be mild to very severe depending upon the degree of pancreatic destruction leading to impaired insulin production and secretion (19,21,23). Glycemic control may be unstable due to the loss of glucagon secretion in response to hypoglycemia, carbohydrate malabsorption, and inconsistent food intake due to pain and/or nausea secondary to pancreatitis (i.e., “brittle diabetes”) (19,21,23). Whether glycemic control is worse in patients with diabetes secondary to pancreatitis is uncertain as older studies reported worse glycemic control and more recent studies have reported that glycemic control was similar to other patients with diabetes (19). The ability to obtain good glycemic control is likely to be related to the degree of pancreatic insufficiency with patients with a total absence of pancreatic function being more difficult to control.

In patients with relatively mild diabetes treatment with metformin is indicated. A nationwide cohort study in New Zealand and Denmark reported that metformin increased survival in patients with post pancreatitis diabetes (34,35). The GI side effects (nausea, abdominal complaints, diarrhea) of metformin may not be tolerable in some patients with pancreatitis. In observational studies metformin therapy has been associated with a reduction in the development of pancreatic cancer in patients with diabetes (36). Given the increased risk of pancreatic cancer in patients with diabetes and/or pancreatitis, a reduction in the development of pancreatic cancer would be a potential added benefit of metformin therapy (37-39). There are conflicting data on whether treatment with DPP4-inhibitors or GLP1-analogues can cause pancreatitis, but until this issue has been unequivocally settled, it is wise to refrain from using these drugs in patients who have had pancreatitis without a clear reversible etiology (for example, gallstone pancreatitis status post cholecystectomy). Note that two meta-analyses have demonstrated an 80% increased risk of acute pancreatitis in patients using DPP-4 inhibitors compared with those receiving standard care (40,41). In contrast, meta-analyses of large cardiovascular outcome studies have not demonstrated an increase in pancreatitis in patients treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists, but these studies typically excluded patients with a history of pancreatitis (42,43). Thiazolidinediones should probably be avoided as patients with pancreatitis and malabsorption are at increased risk for osteoporosis and thiazolidinediones may potentiate this problem.

Chronic pancreatitis is a progressive disease and therefore it is likely that glycemic control will worsen overtime and most patients will eventually require insulin therapy (23). Many patients will have severe insulin deficiency and will need to be treated with insulin therapy using regimens employed in patients with T1D. Because of the absence of glucagon secretion patients with diabetes secondary to pancreatitis are more susceptible to severe hypoglycemia with insulin therapy but diabetic ketoacidosis is not commonly observed due to the absence of glucagon.

Patients with diabetes secondary to pancreatitis are at risk for microvascular complications and lower extremity arterial disease and therefore routine testing for eye disease, kidney disease, foot ulcers, and neuropathy should be instituted (44-47).

Finally, it should be recognized that patients with diabetes secondary to pancreatitis will almost always have exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (31). Many patients with chronic pancreatitis manifest fat malabsorption without symptoms and therefore a thorough evaluation is required. Oral pancreatic enzyme replacement is beneficial for these patients. Of note, pancreatic enzyme supplementation can improve incretin secretion and thereby may benefit glycemic control (21,25,48). Fat soluble vitamin deficiency commonly occurs (Vitamin A, D, and K) and many patients require supplementation with fat-soluble vitamins.

Pancreatectomy

The metabolic abnormalities that occur after pancreatic surgery depend on the amount and area of the pancreas removed and whether the remaining pancreas is normal or diseased (24). The basis for this variability is due to the distribution of β and non-β islet cell types in the pancreas. Islet density is relatively low in the head of the pancreas and gradually increases through the body toward the tail region by greater than 2-fold and thus α- and β-cells predominate in the tail. In contrast, the cells that secrete pancreatic polypeptide are mainly localized in the head of the pancreas. Distal pancreatectomy usually causes little change in the metabolic status unless more than 50% of parenchyma is excised in patients with diffuse disease or more than 80% in patients with normal pancreatic function (24). The risk of a patient developing diabetes after a distal pancreatectomy varies greatly (24,49). The risk of new diabetes is reduced with central pancreatectomy compared to distal pancreatectomy (50). Resection of the head of the pancreas results in a decrease in pancreatic polypeptide, hepatic insulin resistance, and fasting hyperglycemia. Approximately 20% of patients develop diabetes after resection of the head of the pancreas (24). It should also be recognized that removal of pancreatic tissue can accelerate the development of T2D by decreasing insulin secretion in patients with impaired glucose metabolism (51).

Patients who have undergone total surgical pancreatectomy have a deficiency of insulin, glucagon, and pancreatic polypeptide and require insulin treatment. In general, there are several differences from typical T1D, including exocrine deficiency, low insulin requirements, and a higher risk of hypoglycemia due to the decrease in glucagon, which stimulates hepatic glucose production (glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis). Pancreatectomized patients are prone to hypoglycemia and a delayed recovery from hypoglycemia. In an evaluation of 180 patients post total pancreatectomy 42% experienced one or more hypoglycemic events on a monthly basis (52). In addition to treatment with insulin, pancreatic enzyme supplements are always needed. SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists have been shown to improve glycemic control in patients with diabetes post pancreatectomy (53,54). GLP-1 receptor agonists improve postprandial glycemia by decreasing gastric emptying and reducing postprandial responses of gut-derived glucagon (54). Intraportal islet auto transplantation has been used to prevent the development of diabetes with total pancreatectomy and/or reduce the risk of developing difficult to control diabetes (55-57).

Pancreatic Cancer

A high percentage of patients with pancreatic carcinoma have diabetes (21,58). In one study 68% of patients with pancreatic cancer also had diabetes (59). The prevalence of diabetes in patients with pancreatic cancer is much higher than in other common malignancies (58,59). In patients with pancreatic cancer who also have diabetes, the diagnosis of diabetes occurred less than 2 years prior to the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in 74% of patients (60). In a population-based study less than 1% of patients over the age of 50 with newly diagnosed diabetes were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer within 3 years (61). In a study of 115 patients over 50 years of age who were hospitalized for new-onset diabetes 5.6% were found to have a pancreatic cancer (62). Many patients with pancreatic cancer lose weight and therefore deteriorating glycemic control in conjunction with weight loss and anorexia should raise the possibility of an occult pancreatic cancer (58,63). Other clues to the presence of pancreatic cancer in a patient with new onset diabetes are the lack of a family history of diabetes, a BMI < 25, recent thromboembolism, history of pancreatitis, GI symptoms, and the absence of features of the metabolic syndrome such as dyslipidemia and hypertension. Given the high incidence of diabetes relative to the incidence of pancreatic cancer the routine screening of all patients who develop diabetes is not cost effective. However, in selected patients with the features described above screening is appropriate.

Conversely, long standing T2D increases the risk of developing pancreatic cancer by approximately 1.5 to 2-fold indicating a bidirectional relationship (24,58,64). This risk may persist even after adjustment for obesity and smoking, risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Diabetes is both a risk factor for the development of pancreatic cancer and a complication of pancreatic cancer.

As discussed above diabetes may develop secondary to chronic pancreatitis. Chronic pancreatitis increases the risk of pancreatic cancer. Thus, patients with diabetes secondary to chronic pancreatitis are at a higher risk of developing pancreatic cancer (65).

The strongest evidence linking pancreatic cancer with incident diabetes is the beneficial effects of cancer resection on glycemic control (58). In a small study in 7 patients, Permert and colleagues reported an improvement in diabetes status and glucose metabolism after subtotal pancreatectomy (66). Similarly, Pannala and colleagues in a larger study reported that after pancreaticoduodenectomy, diabetes resolved in 17 of 30 patients (57%) with new-onset diabetes but was unaffected in patients with longstanding diabetes (60). Litwin and colleagues noted similar improvements in glucose metabolism after surgery in patients with pancreatic cancer but a deterioration in patients with chronic pancreatitis (67). Finally, studies have also shown that a good response to chemotherapy in patients with pancreatic cancer can also improve glucose levels (68). Taken together these results demonstrate a benefit from tumor removal and suggest that new-onset diabetes associated with pancreatic cancer may be a paraneoplastic phenomenon.

The mechanism accounting for the development of new onset diabetes by pancreatic cancers is unknown (58). In contrast to other pancreatic disorders the etiology of diabetes is not due to destruction of the pancreas as patients with new onset diabetes and pancreatic cancer have hyperinsulinemia rather than low insulin levels and as noted above the diabetes improves after resection (21). Additionally, pancreatic cancers may be very small and thus unlikely to cause pancreatic insufficiency. Pancreatic cancer is associated with insulin resistance but the factors leading to insulin resistance are unknown (21).

In patients with pancreatic cancer the main goal of the treatment of diabetes is to prevent the short- term metabolic complications and facilitate the ability of the patient to tolerate treatment of the pancreatic cancer (surgery and chemotherapy). Given the poor survival of patients with pancreatic cancer, prevention of the long-term sequelae of diabetes is not a major focus. Metformin is a preferred hypoglycemic agent because there are observational studies suggesting that metformin may improve survival in patients with pancreatic cancer (69-71). However, randomized trials have failed to demonstrate the benefit of metformin therapy in patients with pancreatic cancer (72,73).

Hemochromatosis

Hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by increased iron absorption by the GI tract and increased total body iron stores (74). The excess iron is sequestered in many different tissues including the liver, skin, heart, and pancreas. The classic triad of hemochromatosis is diabetes mellitus, hepatomegaly, and increased skin pigmentation (“bronze diabetes”), but clinical features also include gonadal failure, arthropathy, and cardiomyopathy (74).

In early studies diabetes was present in over 50% of patients with hemochromatosis (75,76). More recently the prevalence of diabetes in patients with hemochromatosis has decreased to approximately 20% of patients, presumably due to the early diagnosis and treatment of hemochromatosis due to genetic testing (75-78). In patients with hemochromatosis screening for the presence of diabetes should be periodically carried out.

Diabetes was typically observed in persons who also had severe iron overload and cirrhosis (76). It should be noted that iron overload from any cause can result in diabetes (79). For example, patients with thalassemia develop iron overload due to the need for frequent transfusions (80,81). The prevalence of diabetes in patients with thalassemia has been declining since the more aggressive and widespread use of iron chelation therapy (81).

There are two abnormalities that lead to abnormal glucose metabolism in patients with hemochromatosis and iron overload (75). First, iron overload leads to beta cell damage with decreased insulin production and secretion. Pathologic examination revealed hemosiderin deposition and iron-induced fibrosis of the islets (76). The decrease in insulin secretion is the primary defect leading to the development of diabetes (75,76,78). Of note glucagon secretion does not appear to be deficient in patients with diabetes and hemochromatosis suggesting that the iron overload has a preferential toxicity for beta cells compared to alpha cells (76,82,83). Similarly, basal and stimulated pancreatic polypeptide levels are also not decreased in diabetic patients with hemochromatosis (84). Thus, the hormonal abnormalities differ in patients with iron overload induced diabetes compared to patients with pancreatitis induced diabetes. The second abnormality is insulin resistance that occurs due to iron overload hepatic damage and/or secondary to obesity (75,76). In addition, a genetic predisposition to diabetes potentiates the development of metabolic dysfunction. Many patients with hemochromatosis and diabetes have a relative with diabetes (85).

The typical micro and macrovascular complications of diabetes occur in patients with hemochromatosis (76,85). In a study by Griffiths and colleagues, 11 of 49 patients with hemochromatosis and diabetes had diabetic retinopathy (86). Sixty percent of the patients with hemochromatosis who had diabetes for greater than 10 years had retinopathy. The incidence of retinopathy is similar to that observed in the general diabetes population (85,86). Similarly, Becker and Miller observed that 7 of 22 patients with diabetes and hemochromatosis had pathologic evidence of diabetic glomerulopathy (87).

The treatment of hemochromatosis by phlebotomy has a variable impact on glucose metabolism (75). In patients who do not yet have complications or organ damage an improvement of insulin secretory capacity and normalization of glucose tolerance has been observed (75,76). Glucose metabolism often improves in patients with impaired glucose tolerance (75,88). In patients with diabetes improvement in glucose metabolism by phlebotomy may occur but is not as common as in “pre-diabetics” (75,88,89). In one study 28% of patients with diabetes and hemochromatosis on insulin or oral agents showed improved glucose control following phlebotomy therapy (90).

Cystic Fibrosis

Cystic Fibrosis is an autosomal recessive disorder due to a defect in the chloride transport channel (91). Cystic fibrosis related diabetes is rare in children but is present in approximately 20% of adolescents and 40-50% of adults with cystic fibrosis (92,93). As patients with cystic fibrosis live longer it is likely that the number of patients with cystic fibrosis and diabetes will increase. The development of diabetes is associated with more severe cystic fibrosis gene mutations, increasing age, worse pulmonary function, undernutrition, liver dysfunction, pancreatic insufficiency, a family history of diabetes, female gender, and corticosteroid use (92,93).

The primary defect in patients with cystic fibrosis related diabetes is decreased insulin production and secretion due to fibrosis and atrophy of the pancreas with a reduction of islet mass (92). In addition, mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene may have direct effects on the ability of beta cells to secrete insulin (93,94). Beta cell dysfunction is not complete with residual insulin secretion and thus patients with cystic fibrosis related diabetes do not typically develop ketosis (92). Reduced alpha cell mass also occurs so while fasting glucagon levels are normal, glucagon secretion in response to hypoglycemia is impaired (92). Peripheral and hepatic insulin resistance may also occur secondary to infections, inflammation, and cirrhosis (93).

Some of the clinical features of cystic fibrosis related diabetes are similar to T1D as patients are young, not obese, insulin deficiency is the primary defect, and features of the metabolic syndrome (hyperlipidemia, hypertension, visceral adiposity) are not usually present (92). However, cystic fibrosis related diabetes is not an autoimmune disease (islet cell antibodies are not present) and ketosis is rare because endogenous insulin is still produced (92). Fasting glucose levels are often normal initially with elevated postprandial glucose levels due to a reduced and delayed insulin response to carbohydrates while basal insulin is often adequate to maintain normal fasting glucose levels (95). Patients with cystic fibrosis related diabetes are not at high risk of developing atherosclerosis and heart disease is not a major issue (92-94). This is likely due to malabsorption leading to low life-long plasma cholesterol levels and the shortened length of life (92,93). As life expectancy increases and medical therapy with Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator (CFTR) modulators improves, the risk of macrovascular disease may increase. Microvascular complications do occur in cystic fibrosis related diabetes and are related to the duration of diabetes and glycemic control (92,93,95). The American Diabetes Association recommends screening for complications of diabetes beginning 5 years after the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis related diabetes (96)

Lung disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with cystic fibrosis and both insulin insufficiency and hyperglycemia negatively affect cystic fibrosis lung disease (97). Numerous studies have shown that the occurrence of diabetes in patients with cystic fibrosis is associated with more severe lung disease and increased mortality and this adverse effect disproportionately affects women (92,95,97). In patients with cystic fibrosis lung function is critically dependent on maintaining normal weight and lean body mass. Insulin deficiency leads to a catabolic state with the loss of protein and fat (92). Multiple studies have shown that insulin replacement therapy improves nutritional status and pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis related diabetes (92). In addition, elevated blood glucose levels result in elevated blood glucose levels in the airways, which promotes the growth of pathogenic microorganisms and increases pulmonary infections (92,95). Of note recent studies have shown that the marked increase in mortality in patients with cystic fibrosis related diabetes compared to patients with cystic fibrosis only has decreased (98). It is likely that early diagnosis and aggressive treatment have improved survival in patients with cystic fibrosis related diabetes.

Because of the adverse effects of diabetes on lung function in patients with cystic fibrosis routine screening for diabetes is recommended (97). It is recommended that annual screening begin at age 10 (97). While fasting glucose and A1c levels are routine screening tests for diabetes, in patients with cystic fibrosis these tests are not sensitive enough (97). Fasting glucose and A1c testing will fail to diagnose approximately 50% of patients with cystic fibrosis related diabetes (94,97). However, recent studies have suggested that a screening A1c >5.5% would detect more than 90% of patients with diabetes and therefore with further confirming studies measuring A1c levels could become an initial screening approach (96). As noted above, abnormalities in postprandial glucose characterizes cystic fibrosis related diabetes and it is therefore recommended that an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) be utilized for the diagnosis of diabetes in patients with cystic fibrosis (97). Studies have shown that the diagnosis of diabetes by OGTT correlates with clinically important cystic fibrosis outcomes including the rate of lung function decline, the risk of microvascular complications, and the risk of early death (97). Moreover, the OGTT identified patients who benefited from insulin therapy (97). Additional screening recommendations are shown in Table 3 and the interpretation of these tests are shown in Table 4.

|

Table 3. ADA and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Recommendations for Screening for Cystic Fibrosis Related Diabetes (CFRD) (97)

|

|

1) The use of A1C as a screening test for CFRD is not recommended.

2) Screening for CFRD should be performed using a 2-h 75-g OGTT.

3) Annual screening for CFRD should begin by age 10 years in all CF patients who do not have CFRD.

4) CF patients with acute pulmonary exacerbation requiring intravenous antibiotics and/or systemic glucocorticoids should be screened for CFRD by monitoring fasting and 2-h postprandial plasma glucose levels for the first 48 h. If elevated blood glucose levels are found by SMBG, the results must be confirmed by a certified laboratory.

5) Screening for CFRD by measuring mid- and immediate post-feeding plasma glucose levels is recommended for CF patients on continuous enteral feedings, at the time of gastrostomy feeding initiation, and then monthly by SMBG. Elevated glucose levels detected by SMBG must be confirmed by a certified laboratory.

6) Women with CF who are planning a pregnancy or confirmed pregnant should be screened for preexisting CFRD with a 2-h 75-g fasting OGTT if they have not had a normal CFRD screen in the last 6 months.

7) Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus is recommended at both 12–16 weeks’ and 24–28 weeks’ gestation in pregnant women with CF not known to have CFRD, using a 2-h 75-g OGTT with blood glucose measures at 0, 1, and 2 h.

8) Screening for CFRD using a 2-h 75-g fasting OGTT is recommended 6–12 weeks after the end of the pregnancy in women with gestational diabetes mellitus (diabetes first diagnosed during pregnancy).

9) CF patients not known to have diabetes who are undergoing any transplantation procedure should be screened preoperatively by OGTT if they have not had CFRD screening in the last 6 months. Plasma glucose levels should be monitored closely in the perioperative critical care period and until hospital discharge. Screening guidelines for patients who do not meet diagnostic criteria for CFRD at the time of hospital discharge are the same as for other CF patients.

|

CF= cystic fibrosis; CRFD= cystic fibrosis related diabetes; OGTT= oral glucose tolerance test, SMBG= self-monitored blood glucose

|

Table 4. Criteria for the Diagnosis of Cystic Fibrosis Related Diabetes (97)

|

|

1) During a period of stable baseline health the diagnosis of CFRD can be made in CF patients according to standard ADA criteria. Testing should be done on 2 separate days to rule out laboratory error unless there are unequivocal symptoms of hyperglycemia (polyuria and polydipsia); a positive FPG or A1C can be used as a confirmatory test, but if it is normal the OGTT should be performed or repeated. If the diagnosis of diabetes is not confirmed, the patient resumes routine annual testing.

· 2-h OGTT plasma glucose >200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l)

· FPG >126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/l)

· A1C > 6.5% (A1C <6.5% does not rule out CFRD because this value is often spuriously low in CF.)

· Classical symptoms of diabetes (polyuria and polydipsia) in the presence of a casual glucose level >200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l)

2) The diagnosis of CFRD can be made in CF patients with acute illness (intravenous antibiotics in the hospital or at home, systemic glucocorticoid therapy) when FPG levels >126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/l) or 2-h postprandial plasma glucose levels >200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/ l) persist for more than 48 h.

3) The diagnosis of CFRD can be made in CF patients on enteral continuous drip feedings when mid- or post-feeding plasma glucose levels exceed 200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l) on 2 separate days.

4) Diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus is diagnosed based on 0-, 1-, and 2-h glucose levels with a 75-g OGTT if any one of the following is present:

· FPG >92 mg/dl (5.1 mmol/l)

· 1-h plasma glucose >180 mg/dl (10.0 mmol/l)

· 2-h plasma glucose >153 mg/dl (8.5 mmol/l)

CF patients with gestational diabetes mellitus are not considered to have CFRD, but require CFRD screening 6–12 weeks after the end of the pregnancy.

5) The onset of CFRD should be defined as the date a person with CF first meets diagnostic criteria, even if hyperglycemia subsequently abates.

|

CF= cystic fibrosis; CRFD= cystic fibrosis related diabetes; OGTT= oral glucose tolerance test

There is evidence that elevations in glucose below the levels typically used to diagnose diabetes result in adverse effects on the lungs (95). Thus, some experts recommend that treatment should be considered for individuals with abnormal glucose levels which do not meet the criteria for diabetes if there is evidence of declining lung function or weight loss (95).

A unique feature in the treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis related diabetes is that insulin is the treatment of choice in all patients (97). Studies have shown that cystic fibrosis patients on insulin therapy who achieve good glycemic control demonstrate improvement in weight, protein anabolism, pulmonary function, and survival (97). No specific insulin treatment regimen is recommended, and the regimen should be individualized for the patient. For example, a patient with elevated postprandial glucose levels will benefit from mealtime rapid acting insulin. It should be noted that patients with cystic fibrosis induced diabetes still have endogenous insulin production, which allows for the achievement of good glycemic control. Oral diabetes agents are not as effective as insulin in improving nutritional and metabolic outcomes and therefore are not recommended (97). However, in patients who do not tolerate insulin (for example frequent hypoglycemia), oral agents, such as DPP4 inhibitors, may be beneficial (99). For most patients with cystic fibrosis related diabetes an A1c < 7% is recommended but the A1c goal can be higher or lower for certain patients based on clinical judgement. Also of note is that cystic fibrosis patients require a high-calorie, high-salt, high-fat diet.

Ivacaftor, a Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator modulator, is a relatively new agent to treat cystic fibrosis and has been shown to partially reverse the disease. Interestingly in case reports ivacaftor has been shown to markedly improve glycemic control (93,100). In a recent retrospective observation study approximately 1/3 of patients with CFRD had either a resolution of their diabetes or marked improvement with ivacaftor therapy (101). Additionally, the risk of developing CFRD is decreased in patients treated with ivacaftor (102). Studies using three Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator (CFTR) modulators (elexacaftor /tezacaftor/ ivacaftor) improved glycemic control and reduced insulin requirements (103-105). These beneficial effects are likely to be due to an improvement in insulin secretion and/or insulin sensitivity (93,106,107). Note the response to these Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator (CFTR) modulators depends on the specific mutation causing cystic fibrosis (107).

INFECTIONS

Viral Infections

Viral infections, particularly enterovirus and herpes virus infections, have been postulated to play a role in triggering the autoimmune reaction that leads to the development of T1D (108-111). This phenomenon is discussed in detail in the Endotext chapter on changing the course of the disease in T1D (112). A phase 2 study with the anti-viral agents, pleconaril and ribavirin, demonstrated preservation of residual insulin production in children and adolescents with new-onset T1D (113). In rare instances a viral infection has been associated with the fulminant development of diabetes due to the destruction of beta cells (114). For a review of the link of viral infections with the development of diabetes see a review by Jeremiah and colleagues (111).

Congenital Rubella

Congenital rubella infection has been shown to predispose to the development of T1D that usually presents before five years of age (115). It has been estimated that approximately 1-6% of individuals with the rubella syndrome will develop diabetes in childhood or adolescence (115,116). The mechanism for this association is unknown. In addition, studies have also shown that patients with congenital rubella also develop T2D (116). In one series 22% of individuals with congenital rubella developed diabetes later in life (116). Fortunately, with increased vaccinations, congenital rubella has become a disease of the past in developed countries.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

Meta-analyses and large database studies have demonstrated that hepatitis V virus (HCV) infection is associated with an increased risk of T2D (117-122). In a meta-analysis of 34 studies the risk of diabetes in patients with HCV infection was increased by approximately 70% (117). Moreover, HCV infection is associated with an increased risk of T2D independent of the severity of the associated liver disease (i.e. occurs in patients without liver disease) but the risk of T2D was higher in HCV patients with cirrhosis (118). As expected, the risk of diabetes is increased in HCV patients if the BMI is increased, there is a family history of diabetes, older age, more severe liver disease, and male sex. Conversely, the prevalence of HCV infection in patients with T2D is higher than in non-diabetic controls (118,122,123). In a meta-analysis of 22 studies with 78,051 individuals it was found that patients with T2D were at a higher risk of HCV infection than non-diabetic patients (OR = 3.50; CI = 2.54-4.82) (123). Finally, diabetes is a significant risk factor for the development of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV infected patients (122,124-127).

Given the increased risk of diabetes in HCV infected patients it seems prudent to routinely screen HCV positive patients for diabetes. Conversely, screening patients with diabetes for HCV infection seems reasonable given the availability of drugs that can effectively treat HCV infections.

Patients with diabetes and HCV infection are insulin resistant in the liver and peripheral tissues (122,127,128). Insulin resistance is present in HCV infection in the absence of significant liver dysfunction and prior to the development of diabetes (128). Treatment that reduces viral load decreases insulin resistance and the risk of developing diabetes in HCV (122,128,129). The insulin resistance in individuals with HCV infections may be due to inflammation induced by cytokines such as TNF-alpha or monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, released from HCV-induced liver inflammation (122,127). Additionally, HCV may directly activate the mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathway, inhibiting IRS-1 protein function and thereby down-regulating GLUT-4 and up-regulating the gluconeogenic enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase-2 (122,127). Beta cell dysfunction may also contribute to the development of diabetes during HCV infection (111,130).

Studies have shown that direct-acting antiviral agents that eradicate HCV infection are associated with improved glycemic control in patients with diabetes indicated by decreased A1c levels and decreased insulin use (127,131). Additionally, in a database study of anti-viral treatment for HCV infection, a decrease in end-stage renal disease, ischemic stroke, and acute coronary syndrome was reported in patients with diabetes (132). These beneficial results on key outcomes need to be confirmed in randomized trials (this may be impossible as withholding treatment of HCV is not appropriate). Treatment of diabetes with metformin or thiazolidinediones is preferred as studies have suggested that these drugs may lower the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, liver-related death, or liver transplantation in patients infected with HCV (133,134).

COVID-19

There is a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and COVID-19. Both T1D and T2D are important risk factors for morbidity and mortality with COVID-19 infections, which is discussed in the Endotext chapter entitled “Diabetes Mellitus and Infections” (135). Studies have also shown that COVID-19 infections are associated with hyperglycemia and new onset diabetes (136,137). In a large meta-analysis of 20 studies the risk of new incident type 1 diabetes was increased (HR1.44; 95% CI: 1.13-1.82) and the risk of new incident type 2 diabetes was also increased (HR 1.47; 95% CI: 1.36-1.59) (138). Other meta-analyses have reported similar results (139-142). A meta-analysis observed that the risk of diabetes increased 1.17-fold (1.02-1.34) after COVID-19 infection compared to patients with general upper respiratory tract infections (140). The risk of new diabetes in patients with COVID-19 was highest for patients in intensive care (HR 2.88) and hospitalized patients (HR 2.15) (138). For non-hospitalized patients the risk of developing new diabetes was much lower (HR=1.16; 95% CI: 1.07-1.26; p = 0.002) (138).

A very large data-based study with millions of patients found that the risk of developing T2D prior to the availability of COVID-19 vaccination was increased and that this increased risk was still elevated by approximately 30% 1 year after the COVID-19 infection (143). The risk of developing T2D is highest soon after COVID-19 infection (four times higher during the first 4 weeks) and 60% of those diagnosed with T2D after COVID-19 still had evidence of diabetes 4 months after infection (i.e. persistent T2D) (143). The risk of developing T1D was elevated but this increase was no longer seen one year after the COVID-19 infection (143). The increased risk of developing both T1D and T2D was greater in people who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and therefore the risk of developing diabetes was reduced, but not entirely ameliorated, in vaccinated individuals compared with unvaccinated people (143). The absolute risk of developing diabetes was greatest in patients at increased risk for diabetes (obesity, certain ethnic groups, individuals with “prediabetes”, etc. (143).

The mechanisms that account for an increased risk of diabetes following COVID-19 infections are unresolved. There are a number of suggested mechanisms.

- Diabetes could be secondary to acute illness and stress induced hyperglycemia. Stress induced hyperglycemia has been observed after other acute conditions including other infections (137,144).

- Pre-existing diabetes could first be recognized during a COVID-19 infection or during follow-up. This could account for some of the patients that appear to develop new T2D as many patients with T2D are unaware that they have diabetes (145).

- COVID-19 infection could trigger beta cell autoimmunity. This is particularly relevant to the development of T1D as viral infections have been hypothesized to initiate beta cell autoimmunity (112,137).

- The SARS-CoV-2 virus could directly damage the beta cells leading to decreased insulin secretion and hyperglycemia (137).

- SARS-CoV-2 virus could lead to pancreatitis indirectly affecting beta cell function.

- The strong immune response that is seen in COVID-19 infections (cytokine storm) could indirectly lead to beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Additionally, elevated cytokines could persist for an extended period leading to insulin resistance and abnormal glucose metabolism (146)

- SARS-CoV-2 virus infects adipose tissue and may cause adipose dysfunction (decreased adiponectin and increased insulin resistance) (147,148). Persistent adipose tissue infection could result in inflammation and alteration of adipokines and cytokines leading to diabetes.

- The use of high dose glucocorticoids in patients with severe COVID-19 could lead to hyperglycemia and diabetes.

- Changes in environment that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as decreased exercise, increased food intake, increased weight gain, etc., could enhance the risk of developing diabetes (149).

Hopefully, future studies will better characterize the mechanisms leading to new onset diabetes in patients with COVID-19 infections and determine whether there are unique mechanisms for this association.

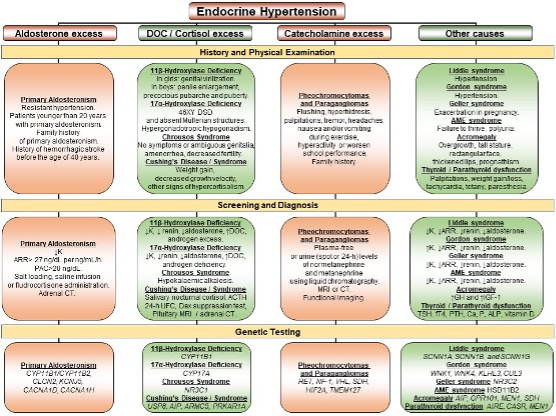

ENDOCRINOPATHIES

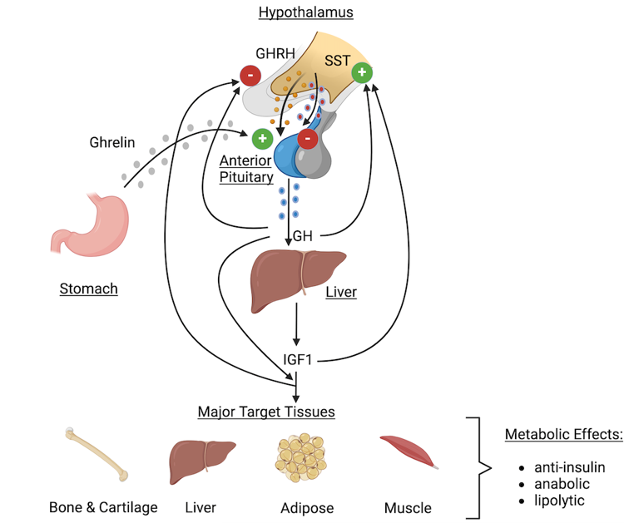

A number of endocrine disorders are associated with an increased occurrence of diabetes (Table 1). Increased levels of growth hormone, glucocorticoids, catecholamines, and glucagon cause insulin resistance while increased levels of catecholamines, somatostatin, and aldosterone (by producing hypokalemia) decrease insulin secretion and hence can adversely affect glucose homeostasis. The disturbance in glucose metabolism occurring secondary to endocrine disorders may vary from a moderate degree of glucose intolerance to overt diabetes with symptomatic hyperglycemia. Additionally, endocrine disorders can worsen glycemic control in patients with pre-existing diabetes.

Acromegaly

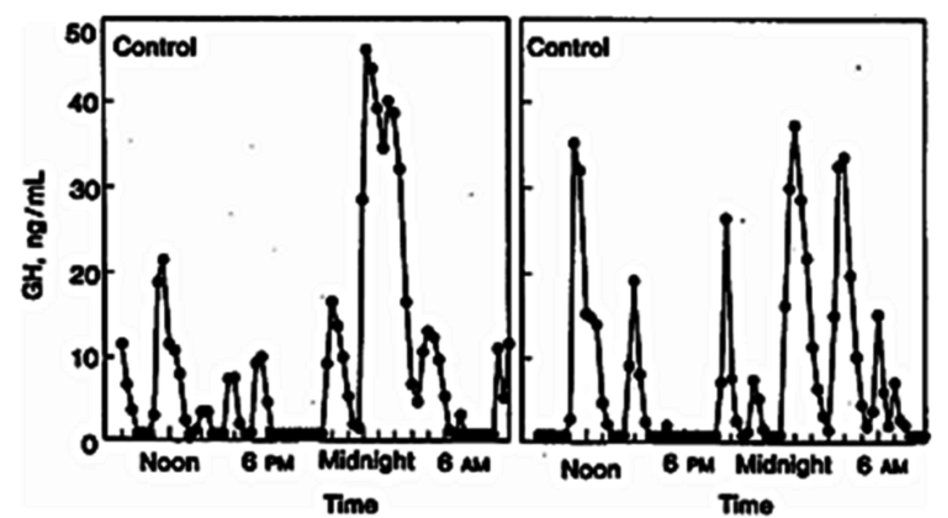

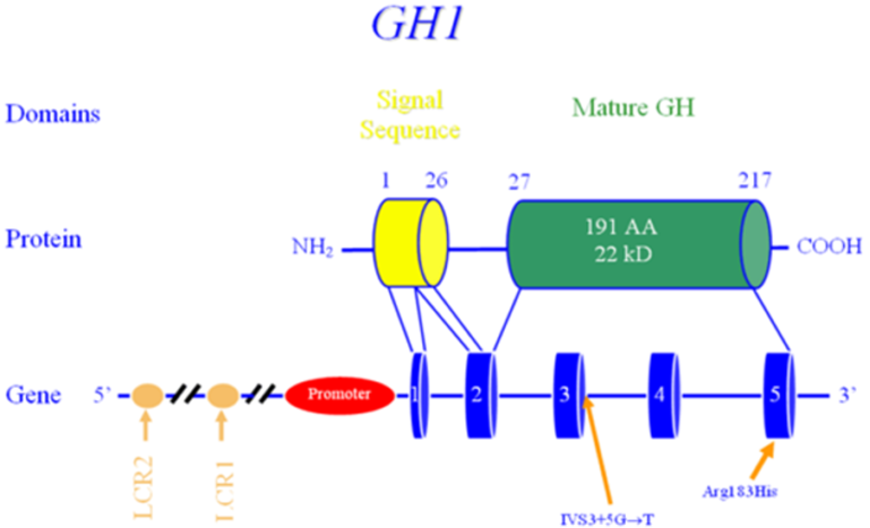

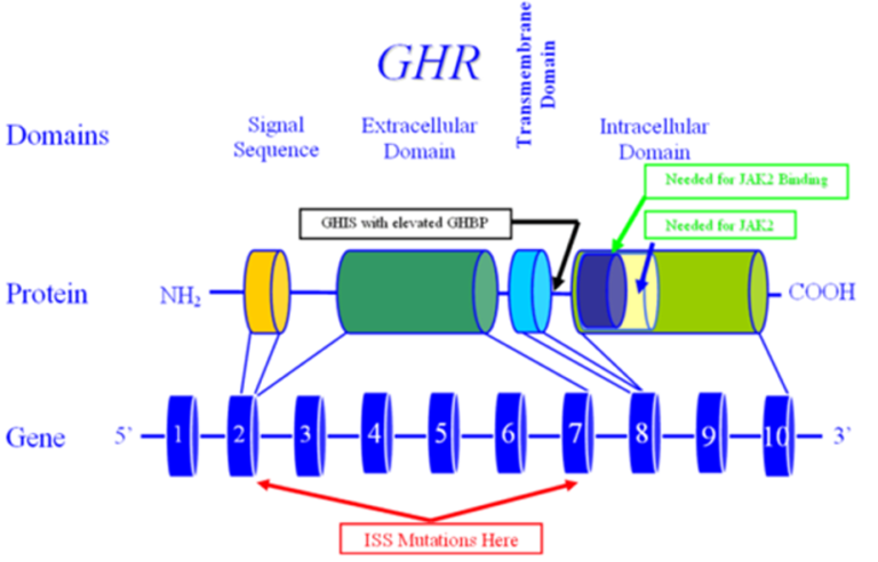

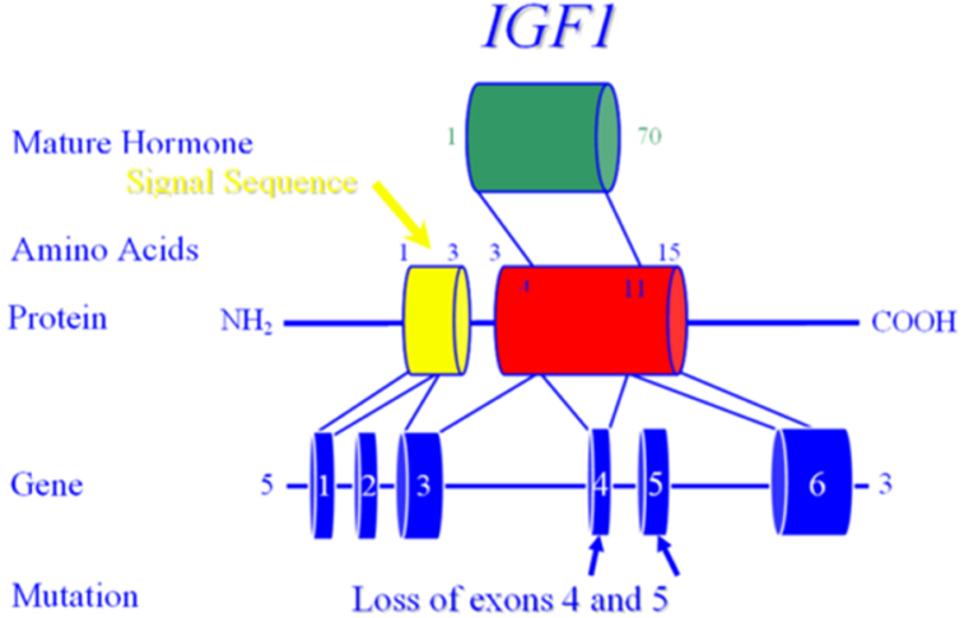

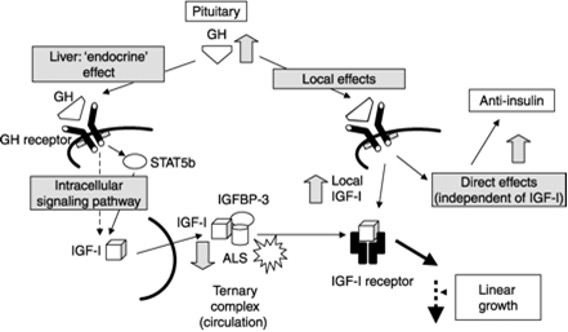

This condition is caused by excessive production of growth hormone (GH) from the pituitary (150). The prevalence of DM in patients with acromegaly is between 10-40%; the prevalence of diabetes and glucose intolerance effects more than 50% of patients (150-153). As expected, there is an increased prevalence of diabetes with age, elevated BMI, a family history of diabetes, and longer duration of acromegaly (151). Diabetes may be present at the time of the diagnosis of acromegaly (154). Higher plasma IGF-1 concentrations correlate with an increased risk of diabetes, suggesting that the biochemical severity of acromegaly influences the risk of developing abnormalities of glucose metabolism (155). Patients with acromegaly should be screened for abnormalities in glucose metabolism (152). The prevalence of acromegaly in patients with diabetes is unknown but is likely to be very low given that acromegaly is an uncommon disorder (60 per million) and diabetes is very common (150).

GH is a counter regulatory hormone to insulin and is secreted during hypoglycemia (156,157). In patients with acromegaly insulin resistance is the major abnormality leading to disturbances in glucose metabolism (151,153,154,158). The insulin resistance is driven primarily through GH induced lipolysis, which results in glucose-fatty acid substrate competition leading to decreased glucose utilization in muscle (151,154,158). Additionally, inhibition of post receptor signaling pathway of the insulin receptor also likely plays a role in the insulin resistance (158). Increased hepatic gluconeogenesis also contributes to the hyperglycemia (151,158). Lipolysis increases the delivery of glycerol and fatty acids to the liver, which serves as a substrate and energy source for gluconeogenesis. In some patients with acromegaly increased insulin secretion compensates for the insulin resistance and glucose metabolism remains normal (151). If insulin secretion cannot increase sufficiently to compensate for the insulin resistance glucose intolerance or diabetes develops (151).

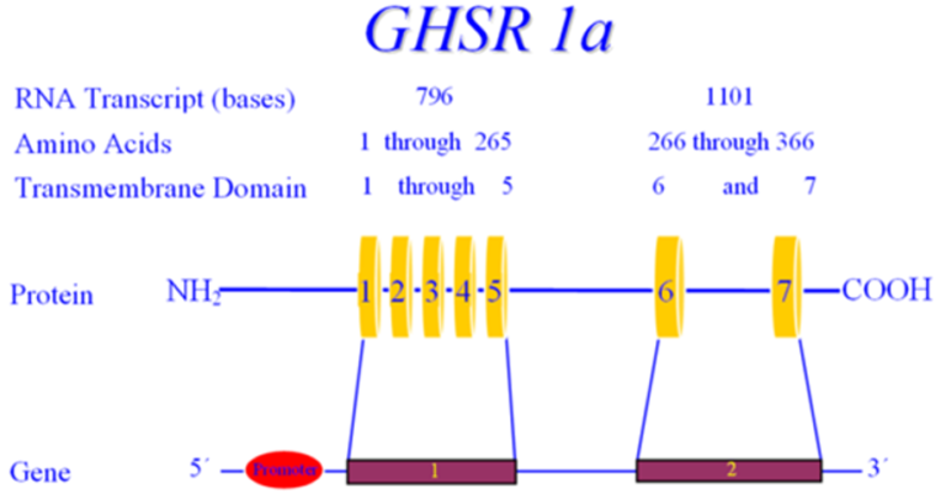

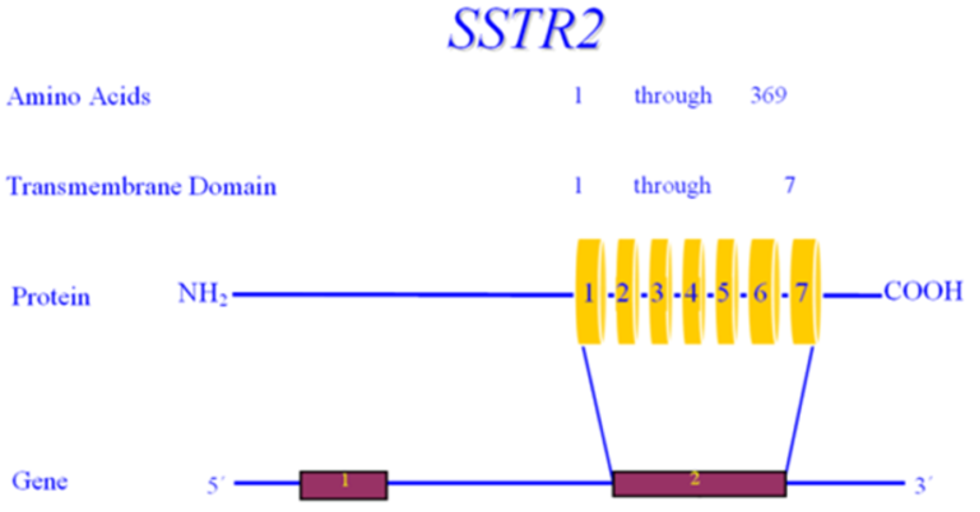

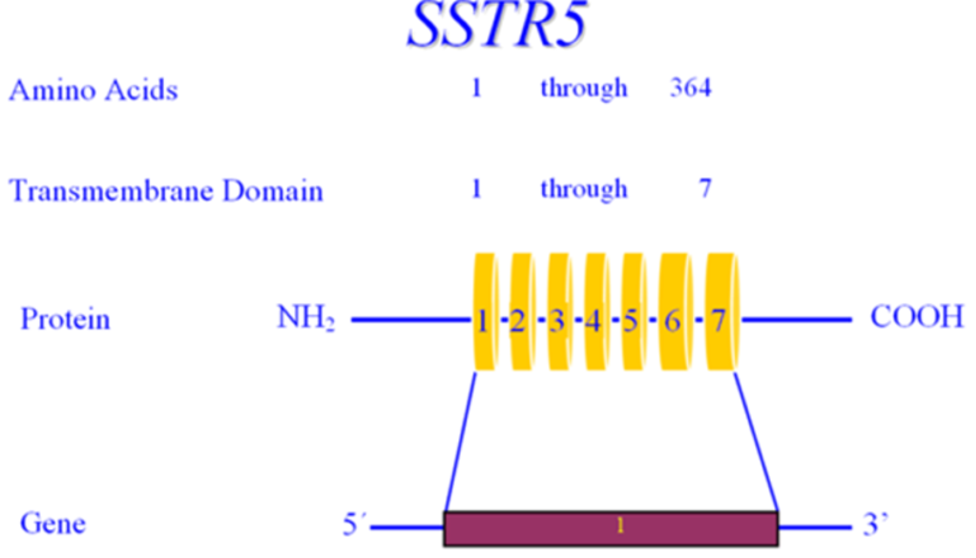

Treatment is directed at the cause of the acromegaly (150). Successful surgical removal of the pituitary adenoma improves hyperglycemia and glucose metabolism has been reported to normalize in 23–58% of people with pre-operative diabetes after surgical cure of acromegaly (151,152,154). Lower IGF-1 and growth hormone levels post operatively correlate with remission of diabetes (159). A meta-analysis of 31 studies with 619 patients treated with somatostatin analogues for acromegaly reported a decrease in insulin levels and glucose levels during a glucose tolerance test but no change in fasting glucose or A1c levels (160). Another meta-analysis of 47 studies with 1297 participants reported that somatostatin analogues also did not affect fasting plasma glucose but worsened 2 hour oral glucose tolerance test and resulted in a mild but significant increase in HbA1c (161) The absence of greater benefit in glucose homeostasis with somatostatin analogues could be secondary to somatostatin analogues inhibiting insulin secretion (150). Of note, while first generation somatostatin analogues appear to have mild or neutral effects on glucose metabolism in patients with acromegaly, treatment with pasireotide, a second-generation somatostatin analogue, aggravated glucose metabolism leading to the development of diabetes in some instances (162-164). The adverse effect of pasireotide is due to inhibiting insulin secretion and decreasing the incretin effect. There is little data on the impact of cabergoline on glucose homeostasis in patients with acromegaly, but the available studies suggest that it modestly improves glucose metabolism or has no effect (152,165). Studies have shown that bromocriptine can improve glucose homeostasis (151,152,166). Finally, treatment with the growth hormone receptor antagonist, pegvisomant, has beneficial effects on glucose homeostasis (164,167,168).

The treatment of diabetes in patients with acromegaly is similar to the treatment in other patients with diabetes (151,153). Patients with acromegaly are often lean with low body fat and therefore dietary recommendations may need to be modified. Additionally, since insulin resistance is the primary defect in patients with acromegaly the use of insulin sensitizers may be especially effective but there are no studies comparing the efficacy of various hypoglycemic agents in patients with acromegaly (151). Data suggests that active acromegaly with elevated GH levels enhances the development of microvascular disease (154). The effect of acromegaly on the development of macrovascular disease is unclear (154). Ketoacidosis is uncommon in patients with diabetes and acromegaly.

Cushing’s Syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome is due to elevated glucocorticoids that can be caused by the overproduction of ACTH by pituitary adenomas or ectopic ACTH producing tumors, overproduction of glucocorticoids by the adrenal glands due to adenomas or hyperplasia, or the exogenous administration of glucocorticoids (169). In patients with Cushing’s syndrome diabetes is present in 20-47% of the patients, while impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) is present in 21-64% of cases (170). Risk factors for the development of diabetes in patients with Cushing syndrome include age, obesity, and a family history of diabetes (170). The prevalence of diabetes varies depending on the etiology of Cushing’s syndrome (pituitary 33%, ectopic 74%, adrenal 34%) (171). In patients with endogenous Cushing’s syndrome the relationship of the degree of hypercortisolism and abnormalities in glucose metabolism has been inconsistent with some studies showing a correlation and other studies no relationship (172). For example, in one study, in patients with endogenous Cushing’s syndrome the prevalence of abnormalities in glucose metabolism and diabetes did not differ in patients with slightly elevated (not greater than 2x the upper limit of normal), moderately elevated (2-5X the ULN), and severely elevated (>5x the ULN) levels of urinary free cortisol (173). In patients with exogenous Cushing’s syndrome high doses of glucocorticoids and longer duration of treatment are more likely to cause diabetes (152,172). Elevated glucocorticoids are more likely to cause high glucose levels in the afternoon or evening and in the postprandial state (152). Hyperglycemia resulting from exogenous steroids occurs in concert with the time-action profile of the steroid regimen employed, such that once daily morning administration of an intermediate acting steroid (prednisone or methylprednisone) causes peak hyperglycemia within 12 hours (post-prandial) while long-acting or frequently administered steroids cause both fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia.

Patients with Cushing’s syndrome should be screened for the presence of abnormalities in glucose metabolism (172). It should be noted that fasting glucose levels are often normal with abnormalities present during an oral glucose tolerance test (170,172). Screening with A1c levels or with an oral glucose tolerance test are therefore preferred. The abnormalities in glucose metabolism may contribute to the increased risk of atherosclerosis in patients with Cushing’s syndrome.

The prevalence of Cushing’s syndrome in patients with diabetes is uncertain with studies reporting very different results ranging from 0 to 9% (172). The selection process used, and the criteria used to determine the presence of Cushing’s syndrome likely greatly influences the results with studies that select patients with marked obesity, poor glycemic control, and poorly controlled hypertension finding a higher percentage of patients with diabetes having Cushing’s syndrome. A recent meta-analysis of 14 studies with a total of 2827 patients with T2D reported that 1.4% had Cushing’s syndrome based on biochemical analysis (174). In a multicenter study carried out in Italy between 2006 and 2008, 813 patients with known T2D without clinically overt hypercortisolism were evaluated for Cushing’s syndrome (175). After extensive evaluation 6 patients (0.7%) were diagnosed with Cushing’s syndrome. Four patients had an adrenal adenoma and their diabetes was markedly improved with the disappearance of diabetes in three patients and discontinuation of insulin therapy in the remaining patient. One patient had bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia and one patient had ACTH dependent Cushing’s syndrome with a normal pituitary MRI.

In approximately 15-35% of patients with an incidental adrenal nodule mild autonomous cortisol secretion with T2D is present (176,177). After surgical removal of the adenoma in patients with autonomous cortisol secretion diabetes normalized or improved in 62.5% of patients (5 of 8) (178). However, not all studies have seen such dramatic improvements in diabetes after adenoma removal (179). Clearly additional studies (preferably large, randomized trials) are required to better define the prevalence of mild subclinical Cushing’s syndrome in patients with diabetes and whether treating the subclinical Cushing’s syndrome in these patients will improve their glycemic control. For a detailed discussion of autonomous cortisol secretion see the chapter on Adrenal Incidentalomas in the Adrenal section of Endotext (180).

Currently, routinely screening patients with T2D for Cushing’s syndrome is not recommended (172). Nevertheless, clinicians should be aware of the possibility of Cushing’s syndrome and screen appropriate patients with T2D (young patients, negative family history of diabetes, patients with physical findings suggestive of Cushing’s syndrome, patients with difficult to control diabetes or hypertension) (172).

Glucocorticoids function as a counter regulatory hormone to insulin and increase in response to hypoglycemia (181). Glucocorticoids disrupt glucose metabolism primarily by inducing insulin resistance in liver and muscle and by stimulating hepatic gluconeogenesis (170,172). The increase in hepatic gluconeogenesis is mediated by several mechanisms including a) directly stimulating the expression of gluconeogenic enzymes b) stimulating proteolysis and lipolysis leading to an increase delivery of amino acids, glycerol, and fatty acids to the liver that provides substrates and energy sources for gluconeogenesis c) inducing insulin resistance and d) enhancing the action of glucagon (170,172). The glucocorticoid induced increase in insulin resistance is due to inhibition of the post-receptor signaling pathway of the insulin receptor, which will result in a decrease in the uptake of glucose by skeletal muscle and adipose tissue (170). In addition to the above glucocorticoids can accelerate the degradation of Glut4 in beta cells, which impairs the ability of beta cells to secrete insulin in response to glucose (182).

Treatment of Cushing’s syndrome by removal of a pituitary tumor, an ectopic ACTH producing tumor, or an adrenal lesion result in a marked improvement in glucose metabolism and in many patients a remission of the diabetes (170,172). In patients with persistent Cushing’s syndrome drug therapy may be needed to normalize cortisol levels. Studies have shown that ketoconazole (200–1200 mg/day), levoketoconazole (150-600 mg twice daily), metyrapone (250–4500 mg/day), mifepristone (300–2000 mg/day) (approved to treat diabetes in patients with Cushing’s syndrome),osilodrostat (1-30 mg twice daily), or cabergoline (1-7mg/day) improves glucose metabolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome (152,172,183). In contrast, pasireotide has been shown to significantly worsen glucose tolerance, despite control of hypercortisolism, in patients with Cushing’s syndrome (152,172,183). In patients with exogenous Cushing’s syndrome it is important to use as low a dose as possible of glucocorticoids for the shortest period of time to avoid complications of therapy including disrupting glucose homeostasis (184).

The management of diabetes in patients with Cushing’s syndrome is similar to the treatment of other patients with diabetes (152,183). Since insulin resistance is a key defect in patients with Cushing’s syndrome the use of insulin sensitizers may be especially effective but there are no studies comparing the efficacy of various hypoglycemic agents in patients with Cushing’s syndrome (152). Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone can increase the risk of osteoporosis, and it should be noted that patients with Cushing’s syndrome also have a high risk of osteoporosis. As noted above, postprandial glucose levels are preferentially increased in Cushing’s syndrome and therefore drugs that lower postprandial glucose levels, such as DPP4 inhibitors, GLP1 receptor agonists, alpha glucosidase inhibitors, and rapid acting insulin may be very useful (152). In glucocorticoid-treated patients requiring a basal-bolus insulin regimen, a higher requirement of short-acting insulin than basal insulin is frequently required (usually approximately 70% of total insulin dose as prandial and 30% as basal) (152). Because of the insulin resistance in patients with Cushing’s syndrome higher doses of insulin are often required to achieve glycemic control. Patients with Cushing’s syndrome are at higher risk for developing macrovascular disease and therefore aggressive treatment of dyslipidemia and hypertension is required (185,186).

Pheochromocytoma

Pheochromocytomas are rare neuroendocrine tumors that secrete norepinephrine, epinephrine, and dopamine (187). In pheochromocytomas the prevalence of diabetes has been estimated to be between 15-40% and impaired glucose tolerance as high as 50% (188-191). Patients with diabetes were older, had a longer known duration of hypertension, higher plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine levels, increased urinary metanephrine excretion, and larger tumors (189-191). Surprisingly the BMI did not differ between patients with and without diabetes perhaps because more active tumors with higher catecholamine levels lead to weight loss (189,190). In most instances the diabetes is relatively mild but in rare instances can be severe with ketoacidosis (192). The association of hypertension with diabetes in a young patient who is not overweight is a clue to the presence of a pheochromocytoma (189).

Catecholamines, acting primarily by the beta-adrenergic receptors, stimulate glucose production in the liver by increasing glycogenolysis and increase insulin resistance leading to a decrease in tissue disposal of glucose, which together result in elevations in glucose levels (193,194). In addition, catecholamines acting via the alpha-adrenergic receptors, inhibit insulin secretion by the beta cells and acting via the beta-adrenergic receptors, increase glucagon secretion by the alpha cells (195). A decrease in insulin secretion and an increase in glucagon secretion would facilitate the development of hyperglycemia.

With tumor resection diabetes resolves or markedly improves in the majority of patients (>50-90%) with a pheochromocytoma (189,190,196). A duration of diabetes of less than 3 years is associated with a remission of diabetes (197). It should be noted that post-surgical removal of a pheochromocytoma, hypoglycemia can occur in approximately 5% of patients (198). Most of these hypoglycemic episodes occur in the first 24 hours and are more likely to occur in patients with large tumors and high urinary metanephrine levels (198). If surgery is unsuccessful the use of alpha and beta blockers may improve insulin resistance and glucose homeostasis (199).

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism induces insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, by increasing intestinal glucose absorption and hepatic glucose production (200,201). Thyroid hormones increase hepatic glucose production by stimulating endogenous glucose production by increasing gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis (201). Hyperthyroidism in patients without diabetes may increase glucose intolerance (202). Whether hyperthyroidism causes frank diabetes is unclear because much of the older literature that purports that hyperthyroidism causes diabetes used criteria for diabetes that differs greatly from current guidelines. For example, the study of Kreines and colleagues reported that 57% of patients with hyperthyroidism had diabetes but the criteria for diabetes was a 1 hour glucose >160mg/dL plus a 2 hour value >120 mg/dL during an oral glucose tolerance test (203). A study from China using oral glucose tolerance tests did not find a major difference in the prevalence of diabetes in patients with Grave’s disease (11.3%) vs controls (10.0%) (204). In a careful review of the literature Roa Dueñas et al found that hyperthyroidism was not related to type 2 diabetes except for one study in which hyperthyroidism had a positive association with the risk of T2D (5 studies, with a total of 148,684 participants and 11,154 incident cases of type 2 diabetes) (200). In a meta-analysis of these studies the results showed a non-significant association with the risk of T2D (HR 1.16; 95% CI 0.90-1.49). A meta-analysis of 12 cohorts with 32,747 participants also failed to demonstrate that subclinical hyperthyroidism was associated with the development of T2D (205). In contrast, a large retrospective cohort study found that after 10 years of follow-up T2D was increased (HR 1.30; 95% CI 1.21-1.39) (206). Thus, the effect of hyperthyroidism on the development of T2D if present is likely to be modest with most studies demonstrating no relationship. The duration of hyperthyroidism may be a key variable and health care systems where hyperthyroidism is promptly treated may fail to demonstrate that hyperthyroidism leads to incident T2D.

It should be noted that hyperthyroidism may worsen glycemic control in patients with diabetes by increasing intestinal glucose absorption, decreasing insulin sensitivity, and increasing glucose production (207). Teprotumumab, which is used to treat thyroid eye disease, may worsen glycemic control in patients with diabetes and induce hyperglycemia in patients without diabetes (208,209) (discussed in drug induced diabetes section below).

Additionally, T1D and Grave’s disease can occur together as part of the autoimmune polyglandular syndrome (210).

Glucagonoma

Glucagonomas are extremely rare and are associated with a characteristic rash termed necrolytic migratory erythema (82% of patients), painful glossitis, cheilitis, angular stomatitis, normochromic normocytic anemia (50-60%), weight loss (60-90%), mild diabetes mellitus (68-80%), hypoaminoacidemia, low zinc levels, deep vein thrombosis (50%), and depression (50%) (211,212). Glucagon stimulates hepatic glucose production by increasing gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis leading to an increase in plasma glucose levels (213). Removal of the tumor results in the remission of diabetes.

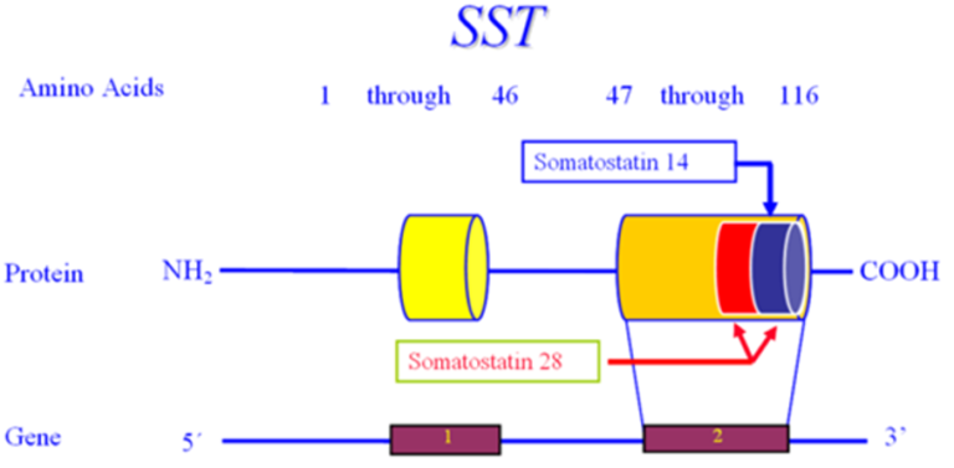

Somatostatinoma

Somatostatinomas are extremely rare tumors that may present with a triad of diabetes mellitus, diarrhea/steatorrhea, and gallstones, but weight loss and hypochlorhydria also occur (214). Approximately seventy-five percent of patients with pancreatic somatostatinomas have diabetes while diabetes occurs in only approximately 10% of patients with intestinal tumors. Typically, the diabetes is relatively mild and can be controlled with diet, oral hypoglycemic agents, or small doses of insulin (214). Somatostatin inhibits insulin secretion which can result in elevations in plasma glucose levels (214). Increased secretion of somatostatin by cells in the pancreas may be in closer proximity to beta cells and more effective in inhibiting insulin secretion than somatostatin secreted by intestinal cells. Somatostatin also inhibits glucagon secretion and therefore diabetic ketoacidosis is very unusual but has been reported (214,215). Additionally, replacement of functional islet cell tissue by the pancreatic tumor may also contribute to the development of diabetes in patients with a pancreatic somatostatinoma (214). Removal of the tumor results in remission of diabetes.

Primary Hyperaldosteronism