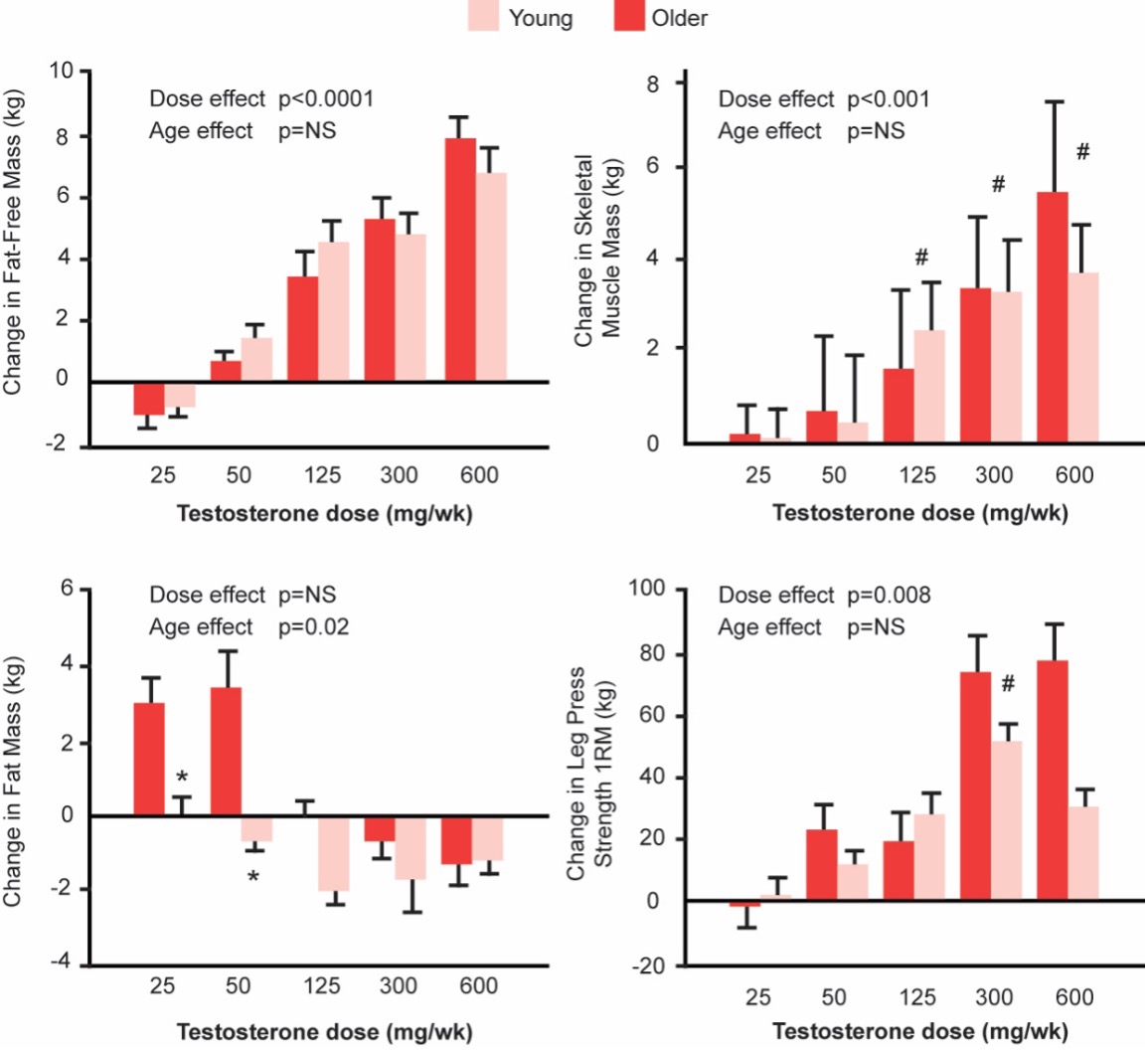

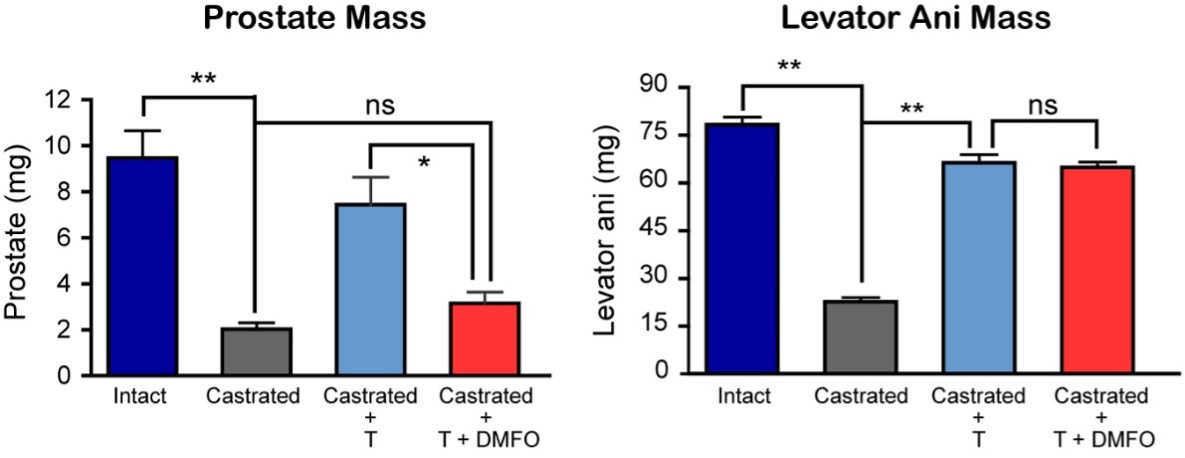

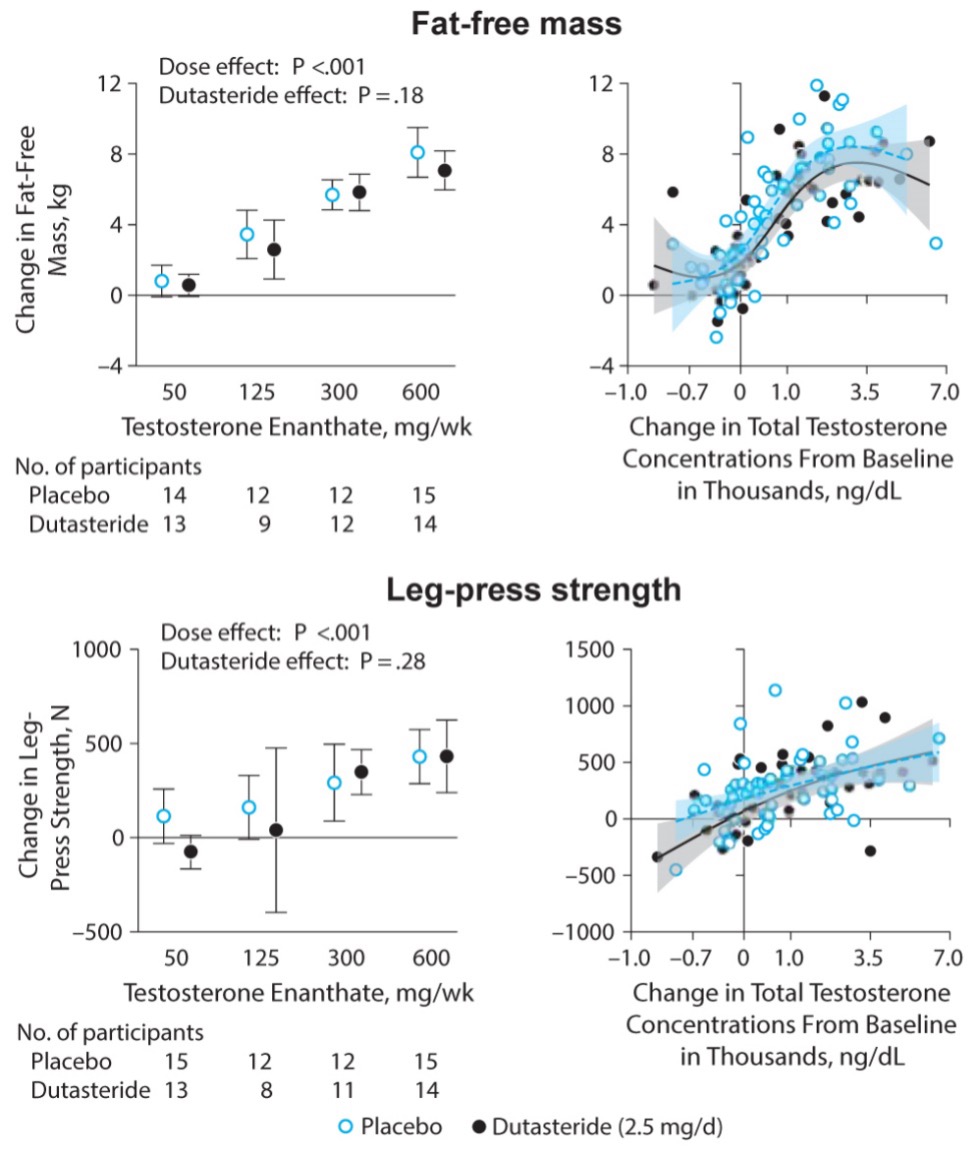

To determine whether testosterone’s effects on muscle mass and strength, sexual function, hematocrit, prostate, sebum production, and lipids are attenuated when its conversion to DHT is blocked, we administered to healthy men, 21-50 years, a long-acting GnRH-agonist to suppress endogenous testosterone. We randomized them to placebo or dutasteride (dual inhibitor of steroid 5-alpha reductase type 1 and 2) 2.5-mg daily, plus 50, 125, 300, or 600-mg testosterone enanthate weekly for 20-weeks (208). Changes in lean and fat mass, leg-press and chest-press strength, were related to testosterone dose but did not differ between placebo and dutasteride groups (208). The relation between testosterone concentrations and the changes in lean body mass, maximum voluntary muscle strength, hematocrit, and sebum production was similar between dutasteride and placebo arms (Figure 9) (208). Changes in sexual-function scores, bone markers, prostate volume, and PSA did not differ between groups (208). These data indicate that testosterone’s conversion to DHT is not essential for mediating its effects on muscle mass and strength, sexual function, hematocrit, or sebum production in men over the range of testosterone concentrations achieved in this trial (208). These data are consistent with studies that have reported that administration of steroid 5α-reductase inhibitors has little or no effect on muscle or bone mass (209-211). The isoforms of steroid 5α reductase enzyme also catalyze the 5α reduction of cortisol, progesterone, bile acids and other metabolites. In the central nervous system, 5α-reductase is the rate-limiting enzyme in the conversion of progesterone to allopregnanolone that serves as a positive allosteric modulator of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptors to modulate neural pathways that regulate mood, affect, and cognition (212-214). Low levels of allopregnanolone have been implicated in the pathogenesis of some forms of depressive and anxiety disorders (215). An intravenous preparation of allopregnanolone was found to be efficacious and approved for the treatment of postpartum depression (216,217) and is being investigated for the treatment of other depressive disorders. Steroid 5α-reductase enzymes are also involved in cortisol metabolism and in the pathogenesis of metabolic disease (218).

Studies of aromatase knockout mice have revealed higher fat mass and lower muscle mass in mice that are null for the P450-linked CYP19A1 aromatase gene (219). Similarly, humans with CYP19A1 mutations have decreased muscle mass and increased fat mass, and they exhibit insulin resistance (220). Data from these experiments of nature suggest that aromatization of testosterone to estradiol is important in mediating androgen effects on body composition. Finkelstein et al (221) have recently examined the relative roles of testosterone and estradiol in regulation of muscle and fat mass, and sexual function. These investigators found that testosterone’s effects on lean mass, muscle size, and strength were not significantly attenuated when its conversion to estradiol was blocked by administration of an aromatase inhibitor (221).

Testosterone is an important regulator of fat mass and distribution. Lowering testosterone concentrations by administration of a GnRH agonist increases fat mass, and testosterone administration in hypogonadal men decreases whole body fat mass (159,222-224). The loss of fat mass during testosterone administration occurs both in the appendices as well as the trunk and is distributed evenly between the superficial subcutaneous and deep intra-abdominal and intermuscular compartments (166,223). The effects of testosterone on whole body fat mass are related to the administered testosterone dose and the circulating testosterone concentrations (166,223).

The effects of testosterone on fat mass are mediated through its conversion to estradiol by the aromatase enzyme encoded by CYP19A1 (221). Men with inactivating mutations of CYP19A1 are characterized by increased fat mass, metabolic syndrome, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance (225-227). Estradiol replacement of male aromatase knockout mice reverses the adiposity and metabolic abnormalities associated with estrogen deficiency (228).

Testosterone regulates adipose tissue mass and metabolism through multiple mechanistic pathways. Androgens inhibit adipogenic differentiation of multipotent mesenchymal progenitor cells; these effects are blocked by androgen receptor blocker, bicalutamide (200,201,229). Testosterone regulates fat oxidation but does not appear to affect triglyceride secretion over short durations (230).

Testosterone, after its aromatization to estradiol, acts through the estrogen receptors in specific brain regions to regulate eating behavior, energy expenditure, and adipose tissue metabolism. The deletion of estrogen receptor α (ER-α) in specific brain regions is associated with adiposity, hyperphagia, and hypometabolism (231); estradiol acting through ER-α regulates eating behavior and energy expenditure differentially through actions on different hypothalamic neurons (231). Activation of estrogen receptor β (ER-β) by selective agonists inhibits weight gain, adiposity, increases energy expenditure and thermogenesis, and reverses hepatic steatosis in mice through direct effects on xenobiotic and bile acid receptors in the liver (232).

Sexual function in men is a complex process that includes central mechanisms for regulation of sexual desire and arousal, and local mechanisms for penile tumescence, orgasm, and ejaculation (233). Primary effects of testosterone are on sexual interest and motivation (233-238). Testosterone replacement of young, androgen deficient men improves a wide range of sexual behaviors including frequency of sexual activity, sexual daydreams, sexual thoughts, feelings of sexual desire, attentiveness to erotic stimuli, and spontaneous erections (233-241). Kwan et al (237)demonstrated that androgen-deficient men have decreased frequency of sexual thoughts and lower overall sexual activity scores; however, these men can achieve erections in response to visual erotic stimuli. Hypogonadal men have lower frequency and duration of the episodes of nocturnal penile tumescence; testosterone replacement increases both the frequency and duration of sleep-entrained, penile erections (239-241). Although both orgasm and ejaculation are believed to be androgen-independent, hypogonadal men have decreased ejaculate volume and their orgasm may be delayed.

Although hypogonadal men can achieve erections, it is possible that achievement of optimal penile rigidity might require physiologic testosterone concentrations. Testosterone regulates nitric oxide synthase activity in the cavernosal smooth muscle (242). Testosterone administration in orchiectomized rats increases penile blood flow and has trophic effects on cavernosal smooth muscle (243-245).

In male rodents, all measures of mating behavior are normalized by relatively low testosterone levels that are insufficient to maintain prostate and seminal vesicle weight (246,247). Similarly, in men, sexual function is maintained at relatively low normal levels of serum testosterone (221,238,248). Testosterone’s effects on libido are mediated through its conversion to estradiol (221).

Total and free serum testosterone levels are positively associated with sexual desire, erectile function and sexual activity in older men with unequivocally low testosterone levels and symptoms of sexual dysfunction (114). These findings suggest that low testosterone levels may contribute to impaired sexual functioning in older men.

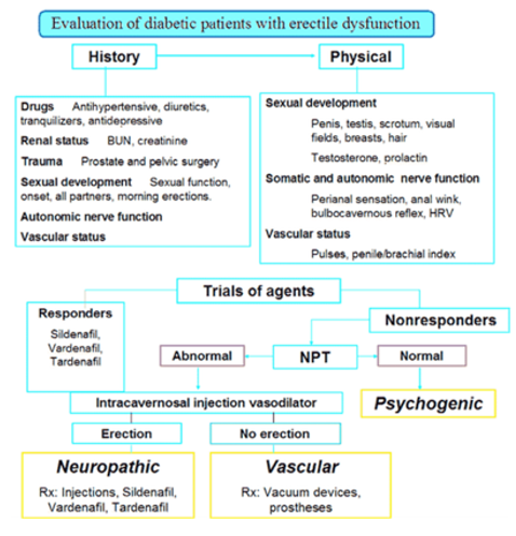

Erectile dysfunction and androgen deficiency are two common but independently distributed, clinical disorders that sometimes co-exist in the same patient (112,113,233,249). Hypogonadism is a clinical syndrome that results from androgen deficiency (16); in contrast, erectile dysfunction is usually a manifestation of a systemic vasculopathy, often of atherosclerotic origin. Thus, androgen deficiency and erectile dysfunction have distinct pathophysiology. Eight to ten percent of middle-aged men presenting with erectile dysfunction have low testosterone levels (113,249-251).

In open-label trials, testosterone treatment has been shown to improve sexual function in young men with classical hypogonadism due to disorders of the hypothalamus, pituitary, or testes (159,252). However, previous trials evaluating the benefits of testosterone therapy in men 60 years and older with age-related decline in testosterone levels on sexual functioning have yielded inconsistent results (253), with some studies showing improvement (254,255), while others have suggested no clear benefit (23). The inconsistencies in these previous studies are due to several factors, including small sample sizes, inclusion of men who were not clearly hypogonadal or did not have sexual symptoms, inclusion of men with heterogeneous sexual disorders, variable treatment durations, and the use of outcomes assessment tools that had not been rigorously validated.

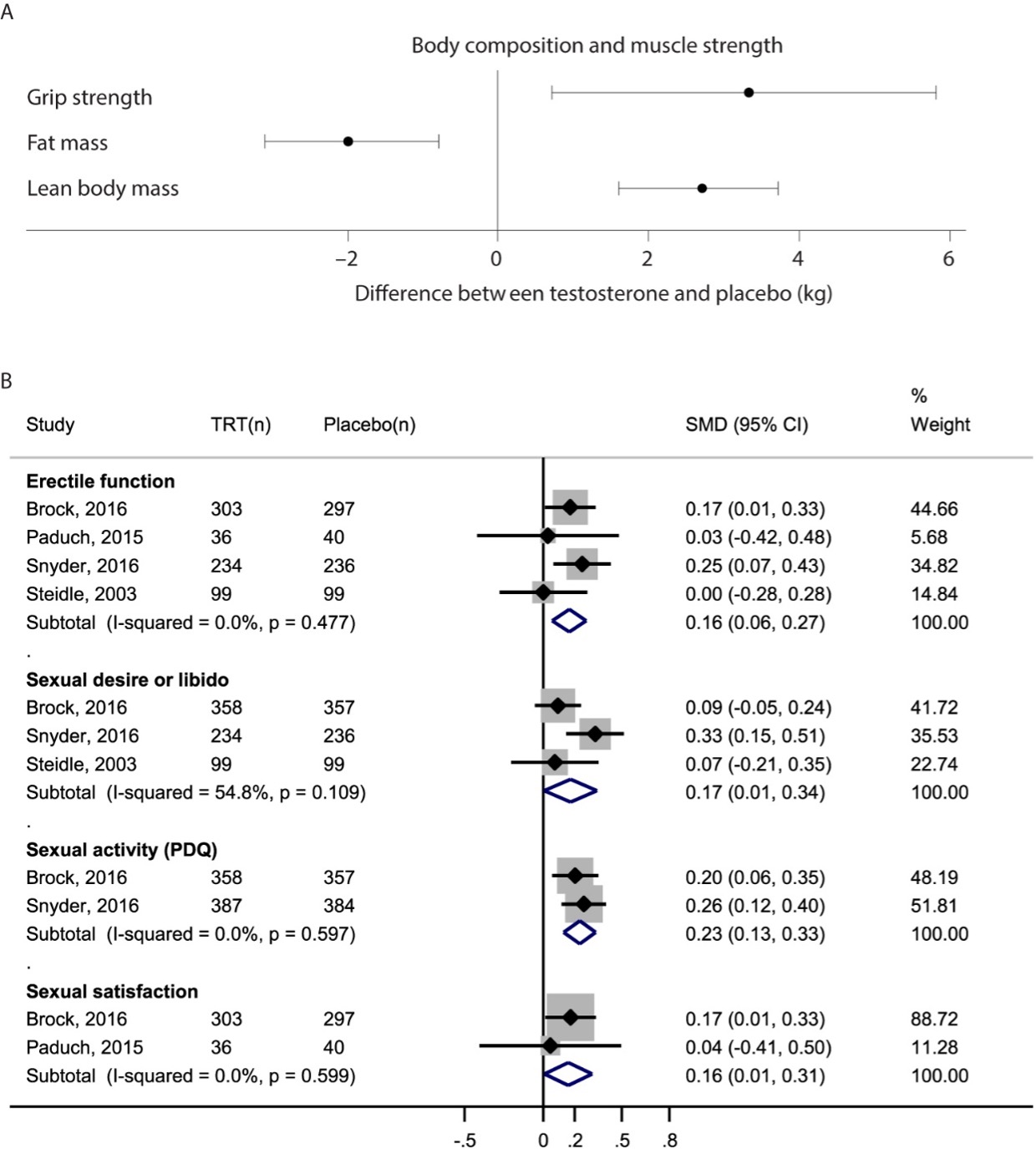

In a small number of placebo-controlled trials of testosterone that have been conducted in men with sexual symptoms and low testosterone levels (24,26,161), testosterone replacement has been associated with a small but significant increase in overall sexual activity, sexual desire, erectile function, and sexual satisfaction. A meta-analysis of these placebo-controlled trials found that testosterone replacement of hypogonadal men is associated with a small but significant increase in sexual desire [standardized mean difference (SMD): 0.17; 95% CI, 0.01, 0.34], erectile function (SMD: 0.16; 95% CI, 0.06, 0.27), and sexual satisfaction (SMD: 0.16; 95% CI, 0.01, 0.31) (256).

The Sexual Function Trial of the TTrials determined the efficacy of testosterone treatment for 1-year on sexual function in symptomatic, community-dwelling, older men ≥65 years with low testosterone levels (26). Testosterone administration for 1-year to raise testosterone concentrations into a range that is mid-normal for healthy young men was associated with significant improvements in sexual activity, desire, and erectile function (257). The treatment effects tended to wane over time, and the effect on erectile function was substantially smaller than that reported with phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors (258). The magnitude of increase in testosterone levels was related to the improvements in sexual activity and desire, but not erectile function (257). There was no clear testosterone threshold level of effect.

Testosterone does not improve sexual function in middle-aged and older men who have normal testosterone levels and do not have any sexual symptoms (23). Testosterone replacement therapy does not improve ejaculatory function in men with ejaculatory disorder (259).

It had been speculated that testosterone administration might improve erectile response of men with ED to selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors (260-262). To determine whether the addition of testosterone to a phosphodiesterase-5-inhibitor improves erectile response, we conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (263), in men, 40-to-70 years, with erectile dysfunction and low total testosterone< 11.5 nmol/L (330ng/dL) and/or free testosterone <173.5 pmol/L (50 pg/mL). All participants were initially started on sildenafil alone and the sildenafil dose was optimized based on their response during a 3 to 7-week run-in period (263). The participants were then randomized to 10-g testosterone or placebo gel for 14-weeks in combination with the optimized sildenafil dose (263). The administration of sildenafil alone was associated with substantial increases in erectile function domain (EFD) score and total and satisfactory sexual encounters (263). However, the change in EFD score in men assigned to testosterone plus sildenafil did not differ significantly from that in men assigned to placebo plus sildenafil (263). Changes in total and successful sexual encounters, quality-of-life, and marital-intimacy did not differ between testosterone and placebo groups. Even among the subsets of men with baseline testosterone <250 ng/dL or those without diabetes, there were no significant differences in EFD scores between the two arms (263). Another placebo-controlled trial of men with erectile dysfunction who were non-responders to tadalafil also did not show a greater improvement in erectile function in men assigned to the testosterone arm than in those assigned to the placebo arm (262). Thus, in randomized trials, the addition of testosterone to PDE5Is has not been shown to improve erectile function in men with erectile dysfunction (262,263).

In older hypogonadal men with low sexual desire, testosterone treatment improves sexual desire, erectile function, and overall sexual activity. Androgen deficiency is an important cause of low sexual desire disorder (233). Therefore, serum testosterone concentrations should be measured in the diagnostic evaluation of hypoactive sexual desire disorder as well as erectile dysfunction, recognizing that low sexual desire is often multifactorial; systemic illness, relationship and differentiation (the ability of individuals in a relationship to maintain their distinct identities) issues, depression, and many medications can be important antecedents or contributors to low sexual desire and sexual dysfunction.

Androgen deficiency that develops before the completion of pubertal development is associated with reduced cortical and trabecular bone mass (272,273). During the pubertal years, bone accretion, and bone length and thickness is regulated by sex steroids. During puberty, sex hormones slow long bone growth and accelerate axial growth. Prepubertal sex hormone deficiency allows continued long bone growth and slows axial growth resulting in longer limbs and a shorter trunk (eunuchoidal proportions) (274). Sex differences in bone width are also established during pubertal development. Men increase bone width by periosteal bone formation and women mostly by endocortical apposition (275). Young men with constitutional delay of puberty have lower bone mineral density (276), which does not improve spontaneously 2 years later (277). Indeed, men with hip fractures have been shown to have smaller femoral head diameters, which may potentially be related to delayed puberty (278). Therefore, individuals with sex-steroid deficiency before or during peri-pubertal years may end up with suboptimal peak bone mass and increased lifetime fracture risk. Similarly, men with acquired androgen deficiency have lower bone mineral density than age-matched controls (155).

Testosterone therapy of healthy, young, hypogonadal men is associated with significant increases in vertebral bone mineral density (156,279-283). However, bone mineral density is typically not normalized after 1-2 years of testosterone replacement therapy (156). Some hypogonadal patients included in these testosterone trials had panhypopituitarism and also suffered from growth hormone deficiency. It is possible that concomitant GH replacement might be necessary for restoration of normal bone mineral density. Excessive glucocorticoid replacement might also contribute to bone loss in these patients. In addition, some participants had experienced testosterone deficiency before the onset and completion of pubertal development; the individuals who develop androgen deficiency during the critical pubertal developmental window of bone accretion, may end up with decreased peak bone mass, and testosterone administration may not be able to restore bone mass to levels seen in eugonadal age-matched controls. Many testosterone replacement trials were less than 3 years in duration, and it is possible that a longer period of testosterone administration might be necessary to achieve maximal improvements in bone mineral density. Indeed, Behre et al (279) reported that bone mineral density in some hypogonadal men continued to increase even after many years of testosterone treatment using a scrotal transdermal patch and reached the levels expected for age-matched eugonadal controls.

The age-related decline in sex hormones is associated with age-related changes in bone mineral density and increased risk of osteoporotic fractures (131-136,284,285). Older men with hip fractures have lower testosterone levels than age-matched controls (286). Bioavailable testosterone levels have been found to be better predictors of fracture risk than total testosterone levels (287). Interestingly, a U-shaped association between endogenous testosterone concentrations and incident fractures was recently observed, with midrange plasma testosterone levels being associated with lower incidence of any fracture and with hip fracture compared to lower or higher testosterone (288). Men with osteoporosis have been found to have lower DHT levels than those without osteoporosis (289). In the Cardiovascular Health Study, in which testosterone and DHT levels were measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, circulating DHT, but not testosterone, was found to be negatively associated with hip fracture risk in men (290).

In epidemiologic studies, estradiol levels are more strongly associated with bone mineral density of the spine, hip, and distal radius than total testosterone levels (132,134,135,285). Men with low bioavailable estrogen have increased risk of non-vertebral fracture which is increased further in those with low bioavailable estrogen, low bioavailable testosterone as well as high SHBG (287) suggesting a complex interplay of these hormones in fracture resilience. Mendelian randomization analysis have found that increased genetically determined estradiol levels are associated with increase in lumbar spine bone mineral density (291) and lower fracture risk (292). The CYP19A1 alleles associated with higher estradiol levels are associated with higher bone mineral density (291).

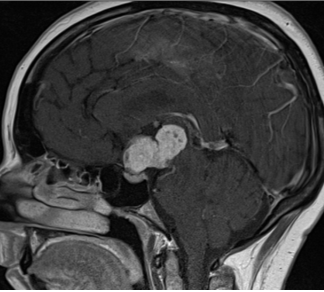

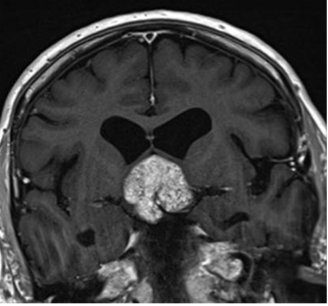

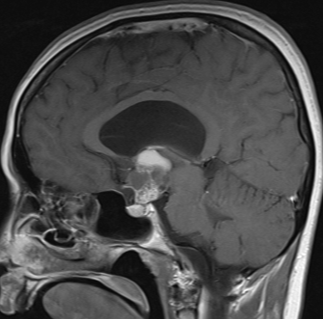

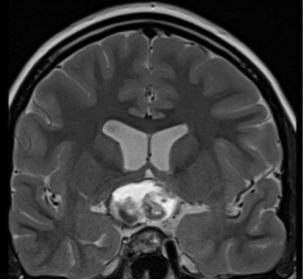

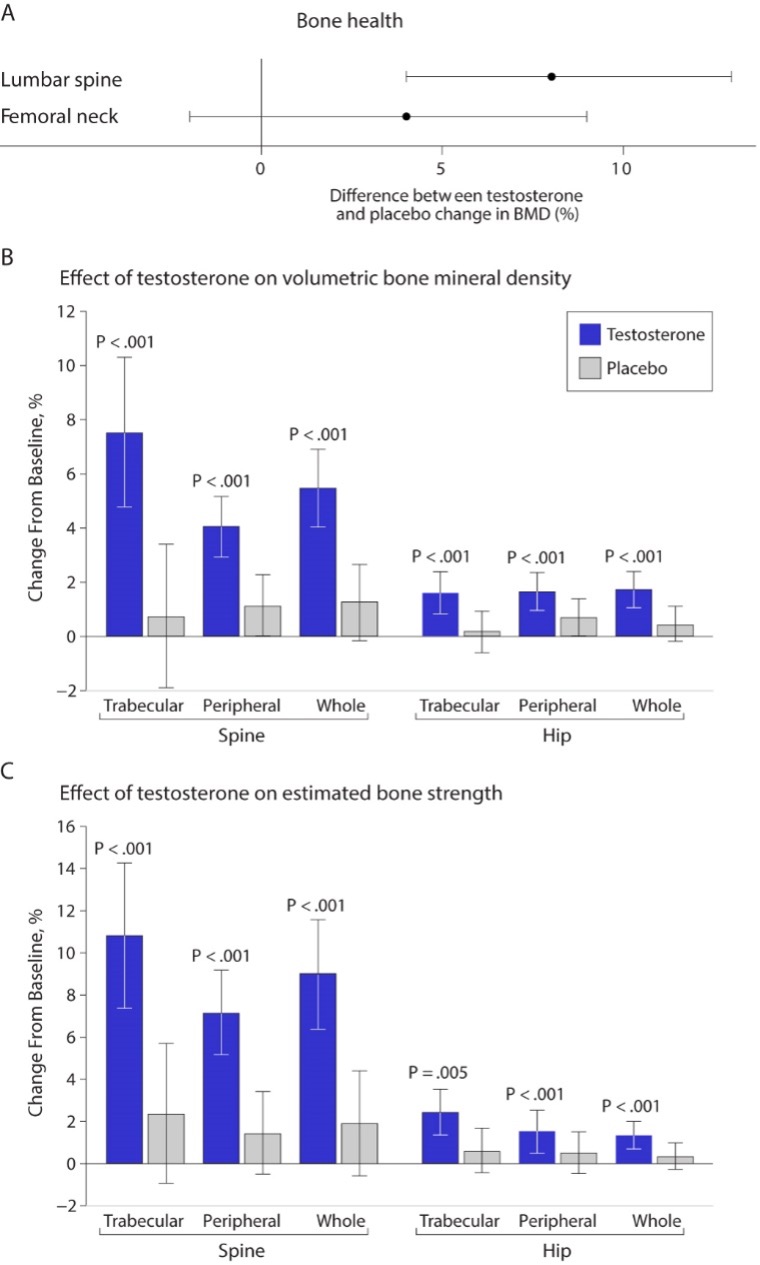

Earlier studies of testosterone replacement of relatively healthy older men that examined the effects of testosterone on bone mineral density reported inconsistent results (188,189,293,294). One study found greater increases in vertebral bone mineral density in the testosterone arm of the trial than in the placebo arm, while another study did not find any significant differences between the change in vertebral or femoral bone mineral density between testosterone and placebo groups (294). A meta-analysis of randomized trials found a significantly greater increase in lumbar bone mineral density but not in femoral bone mineral density in the testosterone arms of trials that used intramuscular testosterone than in placebo arms (Figure 10) (295); transdermal testosterone had no significant effect.

The Bone Trial of the TTrials determined the effects of testosterone replacement for 1-year in men 65 years or older with low testosterone levels on volumetric bone mineral density and bone strength using quantitative computed tomography (296). This trial found significantly greater increases in volumetric bone mineral density and estimated bone strength in the testosterone arms compared to placebo; specifically, these increases were most prominent in the spine than hip and more in trabecular than peripheral bone (Figure 10). The treatment effects on volumetric bone density and bone strength observed in the TTrials compare favorably with those reported in trials of bisphosphonates and some selective estrogen receptor modulators.

The T4Bone substudy of the T4DM trial determined the effect of 24 months of testosterone treatment on bone microarchitecture and bone mineral density of men aged 50 years or older enrolled in a community-based lifestyle program using high resolution-peripheral quantitative computed tomography (297). Compared to placebo, testosterone treatment increased cortical and total bone mineral density of the tibia and radius, as well as cortical area and thickness at both sites. Testosterone treatment also increased areal thickness at the lumbar spine (297).

Future studies are needed to determine whether these improvements from testosterone treatment are associated with reduced fracture risk in older men with low testosterone levels.

Testosterone also directly stimulates osteoblastic bone formation. Androgen receptors have been demonstrated on osteoblasts and on mesenchymal stem cells (313). Testosterone stimulates cortical bone formation (314). Sclerostin is secreted by osteocytes and inhibits osteoblast differentiation. Sclerostin was found to be negatively related to total and free testosterone in men with idiopathic osteoporosis (312). Hypogonadal men have higher serum sclerostin levels than eugonadal men, and DHT directly suppresses sclerostin production in cultured human osteocytes through an AR-mediated mechanism (315). Testosterone also stimulates the production of several growth factors within the bone, including IGF-1; these growth factors may contribute to bone formation (316). Leydig cells in the testis secrete insulin-like peptide 3 (INSL3) in addition to testosterone. INSL3 has been reported to have a negative association with sclerostin in specific populations and INSL3 downregulates sclerostin protein expression in cultured osteocytes (317). Osteocalcin secreted by osteoblasts acts on Leydig cells through the GPRC6A receptor, suggesting a possible feedback mechanism for bone-testis crosstalk (318). Testosterone increases muscle mass, which may indirectly increase bone mass by increased loading. Testosterone might inhibit apoptosis of osteoblasts through non-genotropic mechanisms (319,320). In addition to its effects on bone mineral density, testosterone might reduce fall propensity because of its effects on muscle strength and reaction time.

In men androgens and estrogens both play independent roles in regulating bone resorption (301). Estradiol levels above 10 pg/ml are generally believed to be sufficient to prevent increases in bone resorption and decreases in BMD in men (311).

Testosterone replacement has been shown to increase vertebral and femoral bone mineral density, and bone strength in older men with unequivocally low testosterone levels (16). Testosterone increases bone mass by multiple mechanisms. Testosterone’s aromatization to estrogen plays an important role in regulating bone health in men. Testosterone’s effects on fracture risk have not been studied.

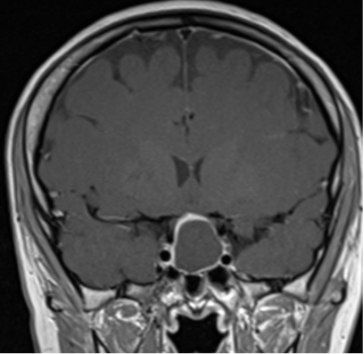

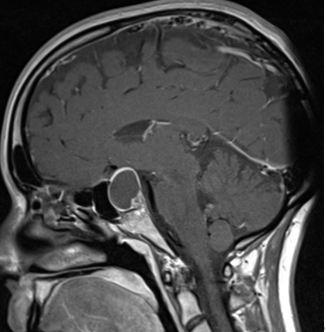

Several lines of evidence suggest that testosterone regulates several domains of cognition, sexually dimorphic behaviors, mood, and affect, and the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Testosterone is aromatized to estrogen in the brain, and some effects of testosterone on cognition might be mediated through its conversion to estradiol. Additionally, androgen receptors are expressed in the brain (330), and androgen effects on brain organization during development (331,332) are mediated through androgen receptor. Androgens increase neurite arborization, facilitating intercellular communication (331-334). Testosterone is metabolized in neurons as well as in glial cells to DHT, which is further converted reversibly in some cell types such as type 1 astrocytes to 5α-androstane-3α,17β-diol (335), which is a potent modulator of GABA on GABAA receptors but a weak ligand for AR and ER (336). The 3β isomer of androstanediol, 5α-androstan-3β,17β-diol, is also synthesized in the brain; this steroid is a ligand for ERβ (337). Thus, testosterone treatment may potentially expose the brain to a range of biologically active metabolites, all of which may contribute to the observed responses. Testosterone also affects serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine (333), and calcium signaling (334). Thus, testosterone could influence cognitive function and the development and progression of AD neuropathology through multiple mechanistic pathways.

The age-related decline in serum testosterone levels has been associated with impairment in cognitive function (338). Androgens effects on cognitive function are domain-specific. For instance, observations that men outperform women in a variety of visuo-spatial skills suggest that androgens enhance visuo-spatial skills (339). In !Kung San hunter-gatherers of Southern Africa, testosterone, but not estradiol, levels correlated with better spatial ability and with worse verbal fluency (340). Women with congenital adrenal hyperplasia with high androgen levels score higher on tests of spatial cognition than their age- and gender-matched siblings (341). 46, XY rats with androgen insensitivity perform worse on tests of spatial cognition than their age-matched controls (342). Other studies have reported a complex relationship between androgen levels and spatial ability (123,343-345). Circulating levels of dihydrotestosterone, a metabolite of testosterone that is not converted to estrogen, positively correlated with verbal fluency (340). Barrett-Conner et al (122) found positive associations between total and bioavailable testosterone levels, and global cognitive functioning and mental control, but not with visuospatial skills. In the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (346), higher free testosterone index was associated with better scores on visual and verbal memory, visuospatial functioning, and visuomotor scanning. Men with low testosterone levels had lower scores on visual memory and visuospatial performance (346); however, some studies have shown no association of serum testosterone levels with domains of visual and verbal memory, and executive function in older men (347,348). In the Concord Health and Aging in Men Project, the authors found that changes in serum testosterone levels over time, rather than baseline testosterone levels, were predictive of cognitive decline (338).

A large body of preclinical and epidemiologic data shows that testosterone acts as a negative regulator of endogenous Ab amyloid accumulation in the brain, attenuates tau phosphorylation, reduces neuro-inflammation, exerts neuronal protective effect in response to injury and disease, and promotes neuronal regeneration and connectivity. However, the randomized trials data generated largely in community dwelling middle-aged and older adults without cognitive deficits or Alzheimer's Disease neuropathology have been inconclusive for reasons that are discussed below.

Testosterone acts as a negative regulator of endogenous Ab amyloid accumulation in the brain through multiple mechanisms. Surgical orchiectomy of male rats is associated with increased accumulation of Ab amyloid in the brain; the accumulation of Ab amyloid in surgically orchiectomized rats is prevented by DHT administration but not by estradiol administration (349-351). In male Brown-Norway rats, age-related decreases in testosterone and DHT are associated with increased brain levels of Ab amyloid (350). Testosterone promotes the conversion of amyloid precursor protein (APP) to soluble APP-alpha rather than A beta amyloid. Consistent with these findings, prolonged treatment of cultured cortical neurons and neuroblastoma cell lines with testosterone resulted in increased production of soluble sAPP-a and decreased production of Ab amyloid (349). This effect of testosterone on the processing of APP is mediated in part through its aromatization to estradiol (352). However, there is strong evidence of mediation through a direct androgen receptor (AR)-mediated pathway as well (350-353).

In 3XTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s Disease, orchiectomy at age 3 months is associated with significantly increased accumulation of Ab amyloid in hippocampus CA1, amygdala, and subinculum at age 6 months (352,353). DHT treatment of orchiectomized mice prevents the accumulation of Ab amyloid as well as deterioration of spontaneous alternation behavior (353). DHT also reduces Tau-phosphorylation in orchiectomized triple transgenic mouse model of AD (352). Androgens upregulate the expression of neprilysin, the enzyme that catalyzes the degradation and clearance of Ab amyloid in neuronal cells (354) and decrease Ab amyloid accumulation (355).

Testosterone also attenuates AD-like tau pathology. In gonadectomized mice, testosterone as well as estradiol reduce tau phosphorylation (356,357). Androgens also reduce tau phosphorylation induced by acute heat shock and injury in male rats independent of estradiol (358).

Testosterone exerts neuroprotective effects across the lifespan in brain areas susceptible to neurodegeneration in AD (365-368). Thus, in cultured neurons, testosterone reduces neuronal apoptosis induced by oxidative stress and Abamyloid (369-371).

Testosterone promotes neuronal growth, connectivity, and functioning. Testosterone increases neurite arborization, and synapse formation facilitating intercellular communication (372-375). Testosterone also has nongenomic effects, and affects serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine and calcium signaling (376-378). Androgen receptors are expressed in the brain, and androgen effects on organization of the brain during development are likely mediated directly through AR. Some additional effects of testosterone are mediated through its conversion to estradiol.

Testosterone also exerts protective effects against neuroinflammation. Orchiectomy as well as obesogenic diet are each associated with increased expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-alpha and IL-1beta in the cerebral cortex in middle-aged male rats (370). The castration-induced upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines TNFa and IL-1b effect is prevented by testosterone supplementation (370). Similar stimulatory effects of testosterone on the expression of proinflammatory cytokines were observed in mixed glial cell cultures in vitro (370). 5aDihydrotestosterone inhibits interleukin-1a or tumor necrosis factor a-induced proinflammatory cytokine production via androgen receptor-dependent inhibition of nuclear factor kB activation (371). Low testosterone also is associated with increased macrophage infiltration in sciatic nerve in castrated male rats (371). The mechanisms of these protective effects of testosterone on neuroinflammation are incompletely understood but appear to require both androgen receptor and estrogen receptor-mediated pathways (371).

Some but not all epidemiologic studies have found an association between low circulating testosterone levels and AD (346,379-384); the relation appears to be stronger between free testosterone levels and the risk of AD than between total testosterone and AD (346). The strength of the association between testosterone and AD is affected by apolipoprotein ε4 genotype, a genetic risk factor for AD (380); men with one or more ε4 alleles have lower testosterone levels and a higher risk of AD than men without an ε4 allele (380).

In longitudinal follow-up of male participants of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (346), the men who were healthy at baseline and developed a clinical diagnosis of AD had significantly lower free testosterone levels than those who did not develop AD. The age-related decline in circulating free testosterone levels preceded the clinical diagnosis of AD by nearly 10 years (346).

Epidemiologic investigations of the association of circulating testosterone levels with age-related changes in cognitive function are in agreement that androgens effects on cognitive function are domain-specific. Generally, men with low testosterone levels perform less well than those with normal testosterone levels on tests of verbal fluency, visuospatial abilities, verbal memory, and executive function (121,122,385-388). Some inconsistency in findings across studies is likely related to heterogeneity of study populations, lack of standardization of cognitive assessments across studies, inaccuracy and imprecision of testosterone immunoassays, and the use of variable thresholds of testosterone levels to define "low". Some studies have suggested a curvilinear relation between testosterone levels and cognitive function; both low and high testosterone levels are associated with worse function suggesting that there may be an optimal level at which cognitive performance is optimized (386).

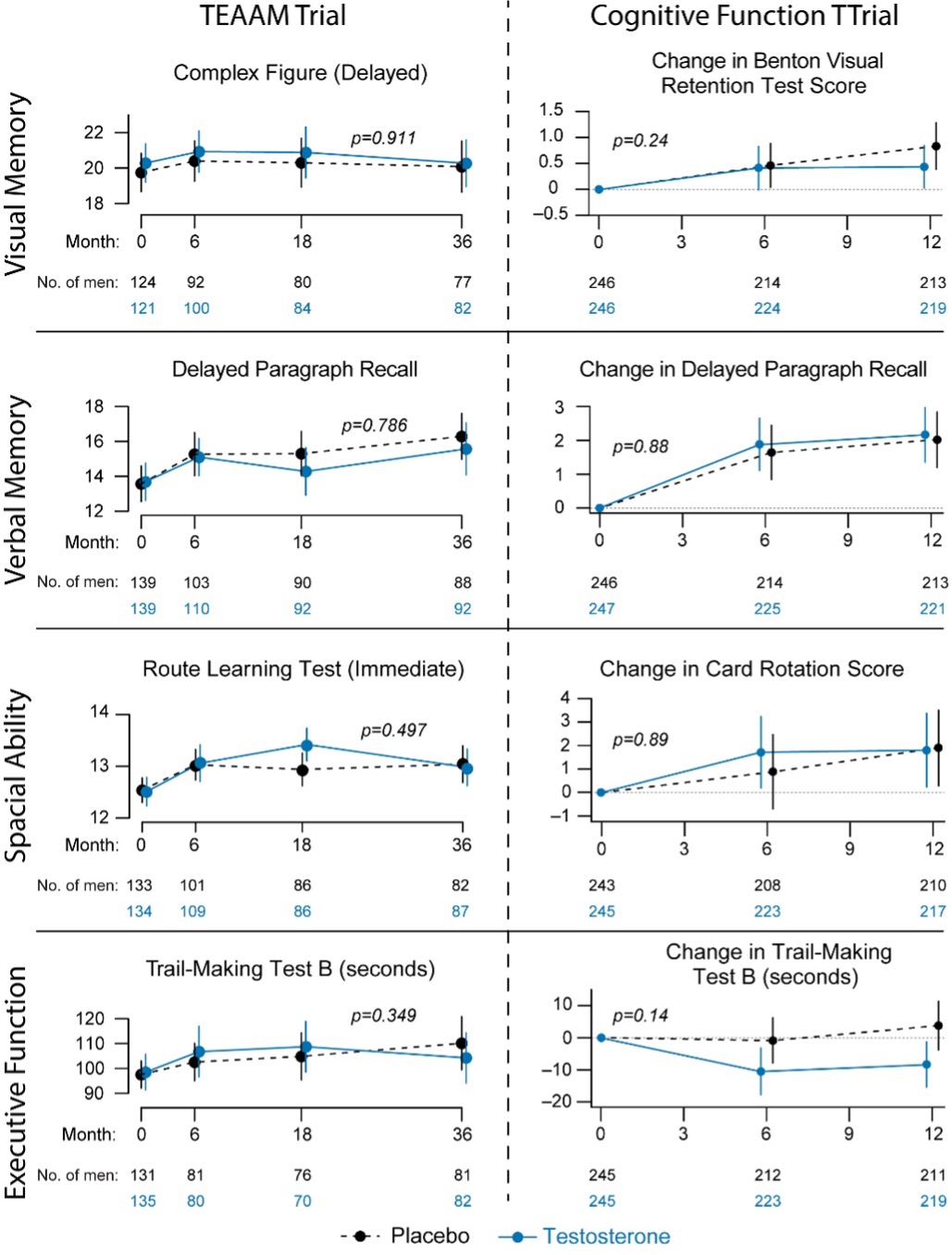

No adequately powered randomized placebo-controlled trials of testosterone replacement have been conducted in men with AD (389-392). The clinical trials data on the effects of testosterone on cognition have provided conflicting results; these trials were limited by their small size, inclusion of men who were not clearly hypogonadal and who did not have cognitive impairment or AD neuropathology, and use of outcomes that were not directly related to AD phenotype. Some studies have reported improvements in verbal memory and visuospatial skill while others found no effect (389,391-393).

The Testosterone Trials, a set of 7 coordinated trials of community-dwelling older men with unequivocally low testosterone levels, measured using liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), showed no significant effect on delayed paragraph recall – the primary outcome of the trial (26,390). Post hoc analysis of the TTrials data showed small but significant improvement in executive function (390). The TTrials had many attributes of good trial design - prospective allocation of participants, parallel groups, blinding, and high retention rates, but progression of AD was not a primary aim of the trial (26). The trial’s duration of one year was not long enough to evaluate effects on clinically meaningful measures of cognitive function or AD pathology. The trial did not include any measures of AD pathology, including A beta amyloid or Tau-protein or blood or CSF markers of AD. The participants in this well conducted trial were not selected prospectively based on cognitive deficits or risk of AD. A few small testosterone supplementation studies (sample size varying from 11 to 47) of 6 weeks to 6-month duration in men with cognitive impairment of AD have reported modest improvements in verbal and spatial memory but the small sample sizes, short intervention durations, variable eligibility criteria, and inclusion of men without confirmed AD, and inclusion of men with normal testosterone levels limit the interpretability of these data (391,392).

In spite of the robust preclinical data that testosterone acts as a negative regulator of endogenous Ab amyloid accumulation in the brain, attenuates tau phosphorylation, reduces neuro-inflammation, exerts neuronal protective effect in response to injury and disease, and promotes neuronal regeneration and connectivity and some epidemiologic evidence that decline in testosterone levels increases the risk of incident clinical AD, the randomized trial data on the effects of testosterone on cognition is highly equivocal. The randomized clinical trials in community dwelling older adults without cognitive deficit or AD neuropathology have not found clinically meaningful improvements in cognitive function. The inconsistency in findings cannot yet be interpreted as conclusive evidence that there is no effect. Limitations of previous studies include limited sample sizes, inclusion of men with no clear cognitive deficit or AD neuropathology, the use of a variety of neuropsychological tests that are not clinically meaningful in the context of AD or dementia; the use of differing protocols in clinical trials. The effects of testosterone therapy on clinically important outcomes in men with cognitive impairment have not been studied. The efficacy of testosterone replacement in men with cognitive impairment, such as in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, needs further investigation in larger randomized controlled trials.

Circulating testosterone concentrations have not been consistently associated with major depressive disorder in men (128,129,395-398). Rather, testosterone levels appear to be associated with a late-life low grade persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) (128,129,395-398). Intervention trials have failed to demonstrate statistically significant or clinically meaningful improvements in patients with major depressive disorder (399). Placebo-controlled trials of testosterone in men with refractory depression also have not consistently shown a beneficial effect of testosterone (399-402). A meta-analysis of randomized trials reported modest improvements in depressive symptoms in testosterone-treated men compared to placebo-treated men (403), but there is no convincing evidence that testosterone treatment can induce remission in men with major depressive disorder (404). Two small trials in men with dysthymia have reported greater improvements in depressive symptoms in testosterone-treated men than in placebo-treated men (405,406). Adequately powered long-term randomized trials are needed to determine whether testosterone replacement therapy can induce remission in older hypogonadal men with late-onset, low grade persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia).

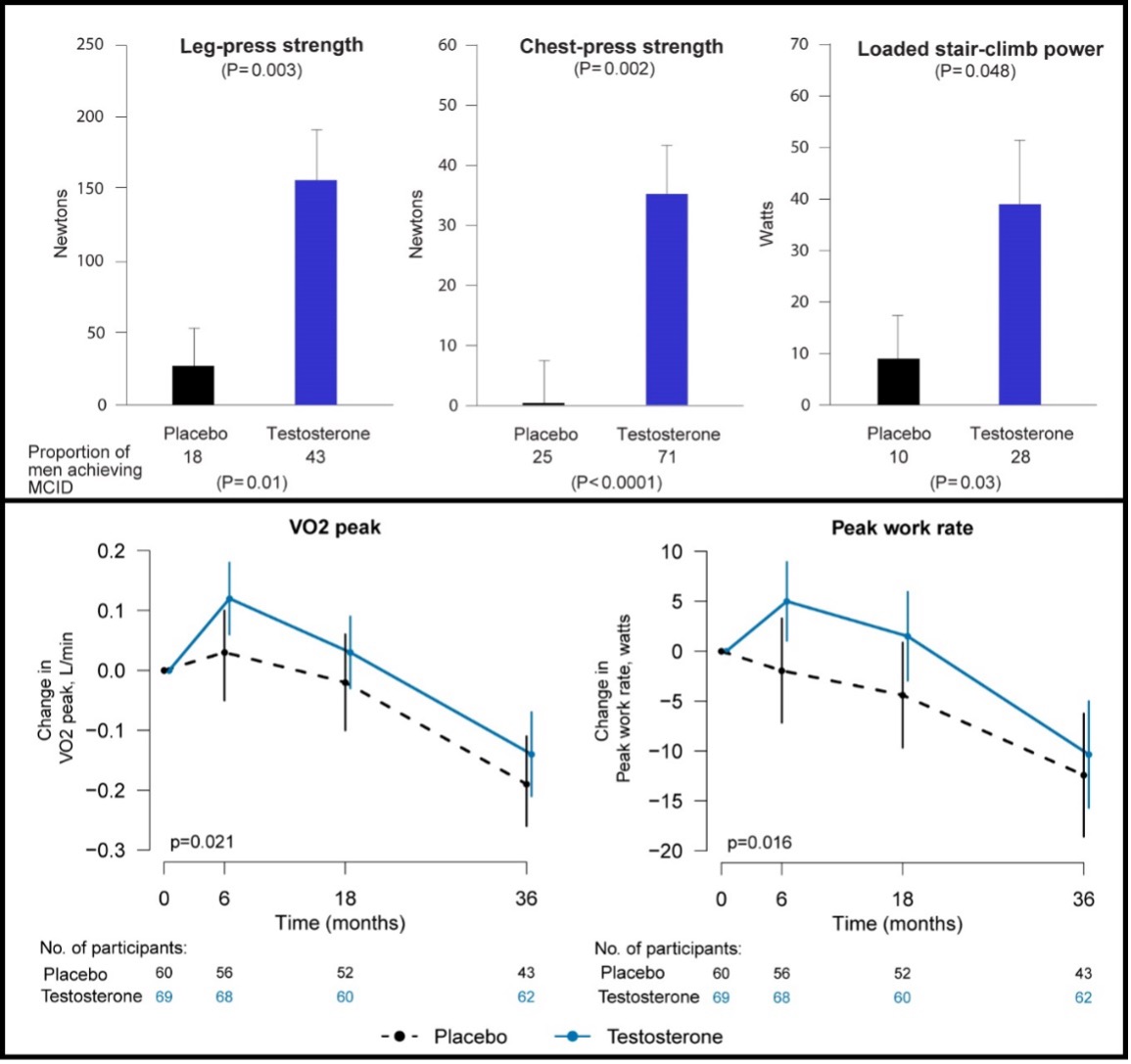

There is anecdotal evidence that androgens improve energy and reduced sense of fatigue (407). Testosterone administration increases hemoglobin and red cell mass, stimulates 2, 3 DPG concentrations thereby shifting the oxygen – hemoglobin dissociation curve favorably to improve greater oxygen delivery, and induces muscle capillarity (322,408,409). Additionally, testosterone stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial quality (410). All of these adaptations would be expected to improve net oxygen delivery to the muscle, improve aerobic performance, and reduce fatigability. The effects of testosterone on fatigue and vitality have been studied in some randomized trials. Endogenous levels of total and free testosterone are not significantly associated with vitality in older hypogonadal men with sexual dysfunction, diminished vitality, and/or mobility limitation (114). In the Vitality Trial of the TTrials, testosterone treatment for 1-year did not improve vitality in older men with low vitality measured using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-scale but men receiving testosterone did report a small but statistically significant improvement in mood. These findings are consistent with other randomized controlled studies (23,171,190), showing no clear benefit on fatigue and health-related quality of life with testosterone therapy.

Supraphysiologic doses of androgenic steroids such as those abused by athletes and recreational bodybuilders have been associated with aggressive responses to provocative situations (411), increased scores on Young’s manic scale, and with affective and psychotic disorders in some individuals (412); these adverse effects have not been reported with physiologic testosterone replacement.

By improving some aspects of physical and sexual function, testosterone supplementation might be expected to improve health-related quality of life. However, only a few small trials have evaluated the effects of testosterone on health-related quality of life. A systematic review of a small number of randomized trials has not revealed a significant improvement in composite health-related quality of life scores, but testosterone therapy improves scores on the physical component of MOS SF-36 (16,159).

Short-term testosterone administration in healthy, young, androgen-deficient men with classical hypogonadism is associated with a low frequency of relatively mild adverse effects such as acne, oiliness of skin, and breast tenderness. However, the long-term risks of testosterone supplementation in older men are largely unknown. There are several unique considerations in older men that may increase their risks of testosterone administration. Serum total and free testosterone concentrations are higher in older men than young men at any dose of testosterone therapy, due to decreased testosterone clearance in older men (61). Older men exhibit greater increments in hemoglobin and hematocrit in response to testosterone administration than young men (321), adjusting for testosterone dose. Altered responsiveness of older men to testosterone administration might make them susceptible to a higher frequency of adverse events, such as erythrocytosis, or to unique adverse events not observed in young hypogonadal men. The baseline prevalence of disorders such as prostate cancer, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and cardiovascular disease that might be exacerbated by testosterone administration is high in older men; therefore, small changes in risk in either direction could have enormous public health impact. Furthermore, the clustering of co-morbid conditions in the frail elderly might render these men more susceptible to the adverse effects of testosterone therapy than healthy young hypogonadal men.

The contraindications for testosterone administration include history of prostate or breast cancer (16). Benign prostatic hypertrophy by itself is not a contraindication, unless it is associated with severe symptoms, as indicated by IPSS symptom score of greater than 21. Testosterone should not be given without prior evaluation and treatment to men with baseline hematocrit greater than 50%, severe untreated sleep apnea, or congestive heart failure with Class III or IV symptoms (16). Testosterone suppresses spermatogenesis and should not be prescribed to men who are considering having a child in the near future.

The risks of testosterone administration include acne, oiliness of skin, erythrocytosis, induction or exacerbation of sleep apnea, leg edema, transient breast tenderness or enlargement, and reversible suppression of baseline spermatogenesis (16) (Table 2). Abnormalities of liver enzymes, hepatic neoplasms, and peliosis hepatis that have been reported previously with orally administered, 17-alpha alkylated androgens, have not been observed with replacement doses of transdermal or injectable testosterone formulations. The two major areas of concern and uncertainty are the effects of long-term testosterone administration on prostate cancer and major adverse cardiovascular events.

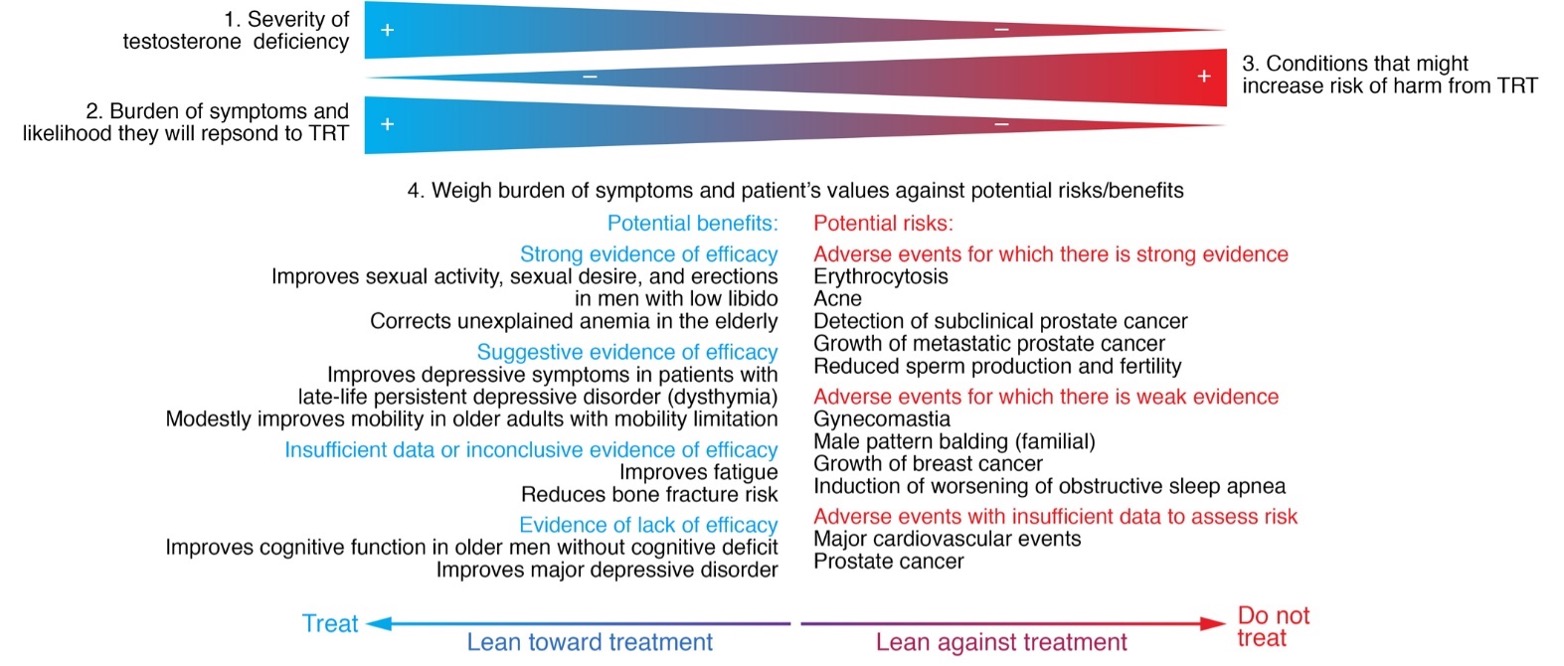

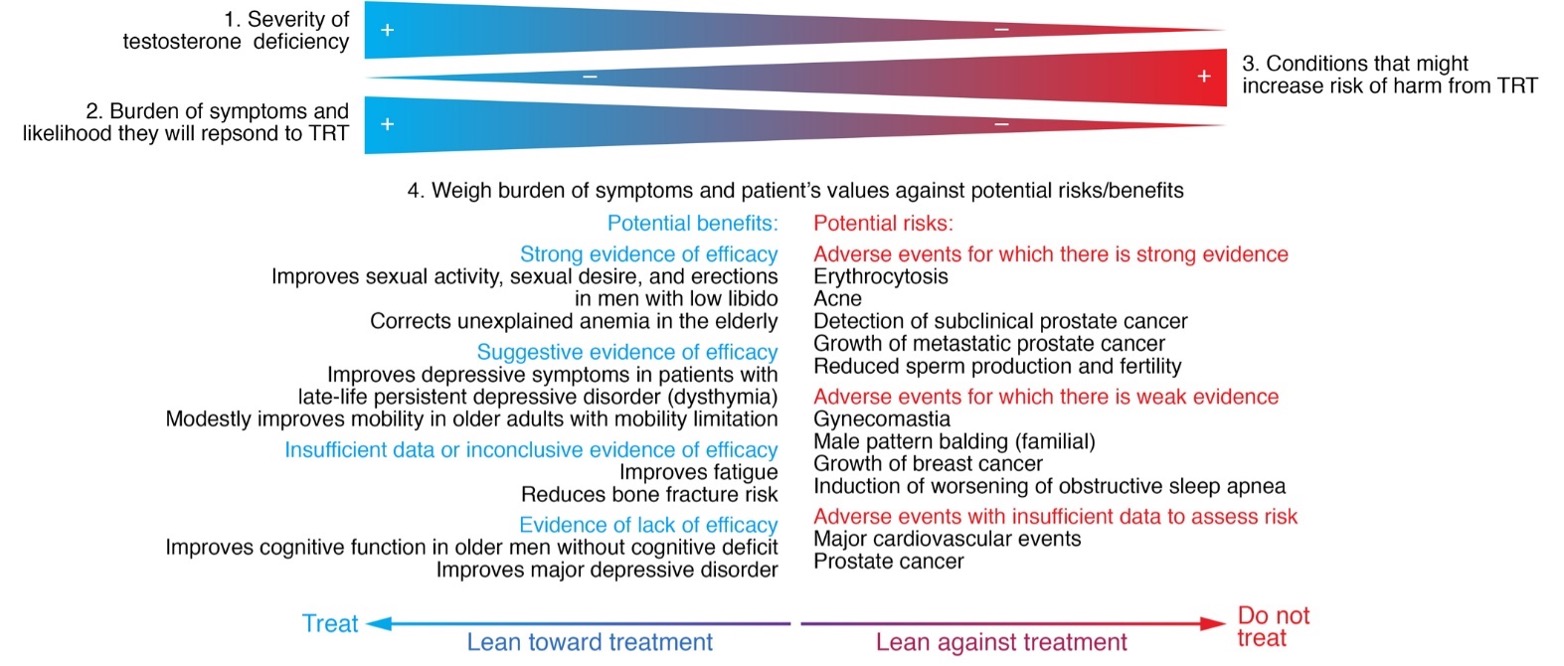

Adapted with permission from the Endocrine Society Guideline for Testosterone Therapy in Men with Hypogonadism in: Bhasin et al J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103(5):1715-1744.

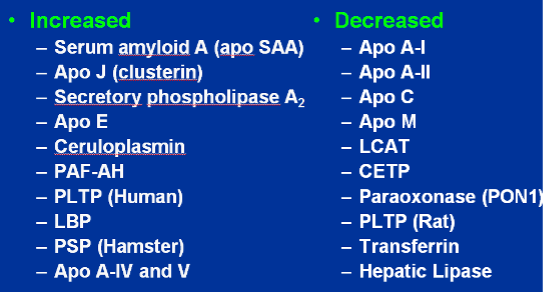

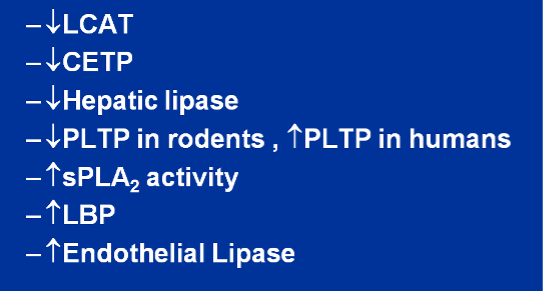

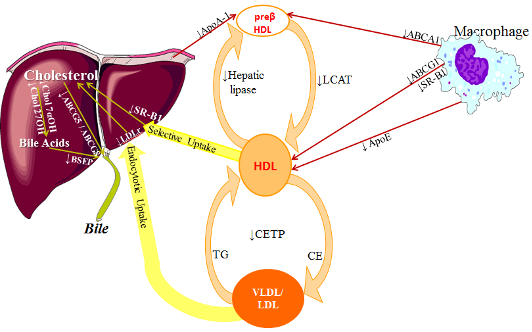

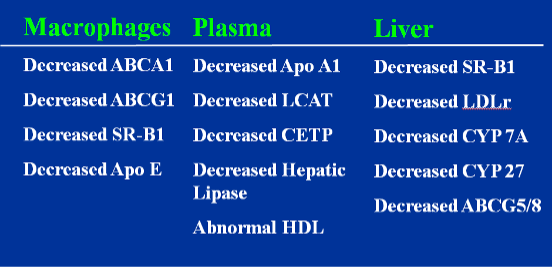

The long-term consequences of testosterone supplementation on the risk of heart disease remain unknown and have been the subject of debate (145,413-417). Some known effects of testosterone such as increase in hematocrit, suppression of plasma HDL cholesterol, and salt and water retention, might be expected to increase cardiovascular risk. Some other effects such as testosterone’s vasodilator effect on coronary arteries resulting in increased coronary blood flow, reduction of whole body and abdominal fat mass, and improved brachial reactivity might be perceived as beneficial. Testosterone’s effects on coagulation are complex; testosterone administration is associated with stimulation of both anti-coagulant and pro-coagulant proteins.

Cross-sectional studies of middle-aged men found a positive relationship between serum testosterone levels and plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations (415,418-421). Lower testosterone levels in men are associated with higher levels of dense LDL particles (418), triglycerides (421,422) and prothrombotic factors (423).

The effects of androgen supplementation on plasma lipids depend on the dose, the route of administration (oral or parenteral), the type of androgen (aromatizable or not), and the subject population (whether young or old, and hypogonadal or not). Supraphysiological doses of testosterone and non-aromatizable androgens frequently employed by bodybuilders undoubtedly decrease plasma HDL-cholesterol levels (424-427). However, administration of replacement doses of testosterone in older men has been associated with only a modest decrease or no change in plasma HDL-cholesterol (16,22,23,25,184,186-189,428-430), and without a significant effect on cholesterol efflux capacity from macrophages (431), suggesting preserved HDL function.

Cross-sectional studies have found a positive association between circulating testosterone concentrations and tissue plasminogen activator activity (432), and a negative relationship between testosterone and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 activity, fibrinogen, and some other prothrombotic factors (432), suggesting an antithrombotic effect of testosterone. However, testosterone increases hematocrit (433), as well as neutrophil, monocyte and platelet counts (434). In men, higher neutrophil counts – even within the normal range - are associated with cardiovascular disease (435). Similarly, higher monocyte counts within the normal range have been suggested as a risk-factor for coronary artery plaque formation and cardiovascular mortality (436). Additionally, testosterone administration increases thromboxane A2 receptor density on human platelets, increasing platelet aggregability ex vivo (437,438). Observational studies have not found a consistent relationship between testosterone treatment and the risk of venous thromboembolism (439-443), although one study reported a small increase in VTE risk in the first few months after starting testosterone treatment (439).

Cross-sectional studies have reported conflicting findings on the association of endogenous testosterone levels and inflammatory markers (444-449). Intervention trials of testosterone generally have not found a significant effect of testosterone on inflammatory markers (430,450). Even supraphysiological doses of testosterone have been found not to affect C-reactive protein (451). Similarly, a prospective cohort study did not find meaningful changes in inflammatory markers in men with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy (452).

Whether variation of testosterone within the normal range is associated with risk of coronary artery disease remains controversial. Of the 30 cross-sectional studies reviewed by Alexandersen (145), 18 reported lower testosterone levels in men with coronary heart disease, 11 found similar testosterone levels in controls and men with coronary artery disease and 1 found higher levels of DHEAS. Prospective studies have failed to reveal an association of total testosterone levels and coronary artery disease (146-150,453-455). The common carotid artery intimal media thickness, a marker of generalized atherosclerosis, is negatively associated with circulating testosterone levels (150).

In some animal models, orchiectomy accelerates and testosterone administration retards atherogenesis progression (466). The protective effect of testosterone on aortic atherogenesis in this preclinical model is mediated through its conversion to estradiol by the CYP19A1 in the blood vessel wall (466).

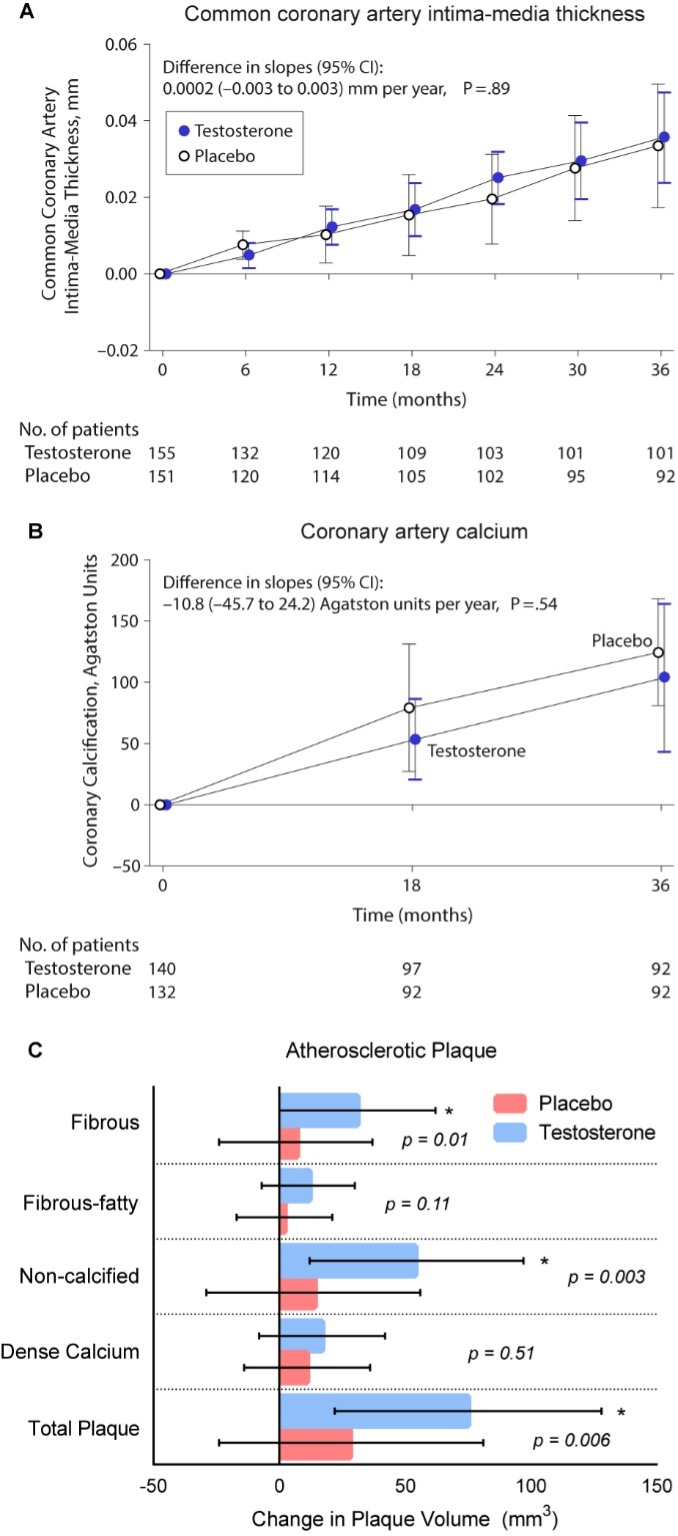

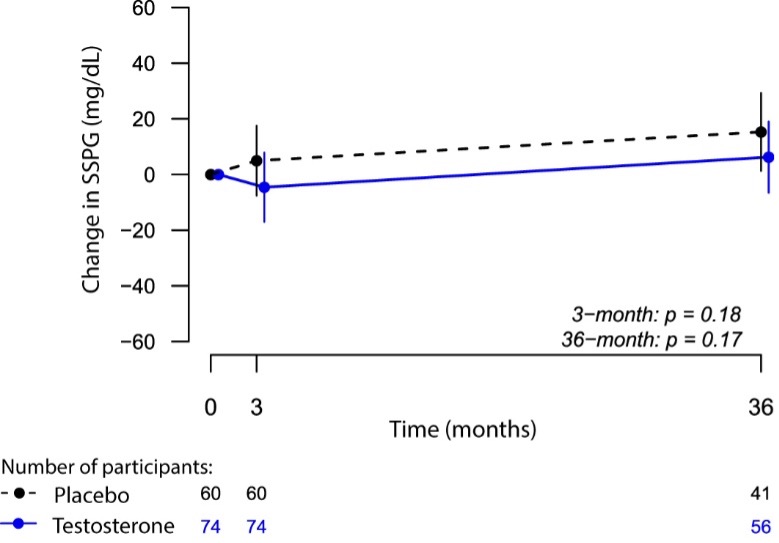

Two large placebo-controlled trials have evaluated the effects of testosterone treatment on atherogenesis progression in middle-aged and older men. The Testosterone’s Effects on Atherosclerosis Progression in Aging Men (TEAAM) Trial determined the effects of testosterone therapy on progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in the common carotid artery using sonographic measurement of common carotid artery intima-media thickness (CCA-IMT) and the coronary artery calcium scores measured using MDCT. The participants in the TEAAM Trial were 308 men, 60 years and older, with total testosterone between 100 and 400 ng/dL or free testosterone below 50 pg/mL (23). Men were randomized to receive either 75 mg of transdermal testosterone gel or placebo gel daily and received for 3 years. Neither the progression of CCA-IMT nor coronary artery calcium scores differed between the men randomized to the testosterone and placebo groups (Figure 12) (23).

In the cardiovascular trial of the TTrials, 138 men with serum total testosterone below 275 ng/dL received either testosterone gel or placebo gel for one year and were evaluated by coronary computed tomographic angiography for progression of non-calcified and calcified coronary artery plaque volume, as well as coronary artery calcium score (467). Consistent with the findings of the TEAAM Trial, the changes in coronary artery calcium scores did not differ between the testosterone and placebo groups over one year of intervention. However, the increase in non-calcified plaque volume (primary endpoint) was significantly greater in men assigned to the testosterone arm than in those assigned to placebo arm (Figure 12) (467); there were baseline differences in non-calcified plaque volume between the two groups. The clinical implications of these findings to cardiovascular risk remain to be established.

Cross-sectional studies have also linked low androgen levels in men to an increased risk of atrial fibrillation (482-484), and normalization of testosterone levels with testosterone replacement is associated with a decreased incidence of atrial fibrillation compared with untreated hypogonadal men (485). These findings need corroboration in randomized trials.

To-date, no randomized trials have been large enough or of sufficiently long duration to determine the effects of testosterone treatment on MACE (416). The frequency of MACE reported in randomized testosterone trials has been low—even lower than that expected for the age and comorbid conditions of the participants (18,486,487). A randomized trial of testosterone in older men (The TOM Trial) with mobility limitation was stopped early due to a higher frequency of cardiovascular-related events in men assigned to testosterone than in those assigned to placebo (22), heightening concern about the cardiovascular safety of testosterone in frail older men. In contrast to many other testosterone trials in older men, which recruited relatively healthy older men, the participants in the TOM trial had a high prevalence of chronic conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia (22). Men, 75 years of age or older, and men with high on-treatment testosterone levels seemed to be at the greatest risk of cardiovascular-related events. In secondary analyses, these events were found to be associated with changes in serum free testosterone and estradiol levels (488). The dose of testosterone used in the TOM trial was higher than that used in some previous trials, but not dissimilar from or lower than that used in some other trials. The cardiovascular events were small in number and of variable clinical significance. The TOM trial was not designed for cardiovascular events; therefore, the cardiovascular events were not a pre-specified endpoint, and were not collected in a standardized manner, nor adjudicated prospectively. Additionally, many of the cardiovascular events were not MACE.

The higher cardiovascular adverse event incidence in testosterone-treated older men observed in the TOM trial was not reproduced in two larger trials of longer duration published more recently; in the TEAAM trial, the incidence of major adverse cardiac events throughout the 3 years of intervention was similar between groups (23). Similarly, in the TTrials, the number of MACE (myocardial infarction, stroke or death related to cardiovascular disease) during the one year of treatment was similar in the two groups, with seven men in each group experiencing an event (26). The number of MACE in the TEAAM and Ttrials were too few to permit strong inferences on the effects of testosterone treatment on MACE.

The Hormonal Regulators of Muscle and Metabolism in Aging (HORMA) trial reported a significantly greater increase in blood pressure in men treated with testosterone than in those treated with placebo (489). Testosterone administration causes salt and water retention (490), which can induce edema and worsen pre-existing heart failure.

The long-term effects of testosterone replacement therapy on MACE remain unknown. The FDA conducted an extensive review and concluded “the studies...have significant limitations that weaken their evidentiary value for confirming a causal relationship between testosterone and adverse cardiovascular outcomes”. Nevertheless, the FDA directed the pharmaceutical companies to add in the drug label information about a possible increased risk of cardiovascular events with testosterone use. An independent review conducted by the European Medicines Agency also found no consistent evidence of an increased risk of coronary heart disease associated with testosterone treatment of hypogonadal men. Long-term randomized trials of the effects of testosterone replacement on MACE are needed and are particularly important because even small changes in incidence rates could have significant public health impact.

A large randomized, placebo-controlled trial to study the effects of testosterone replacement therapy on the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events in men 45 to 80 years of age with low testosterone levels and one or more symptoms of testosterone deficiency, who are at increased risk for cardiovascular events is currently underway (The TRAVERSE Trial, NCT03518034). The intervention duration is up to 5 years in this trial of over 6,000 men. The efficacy outcomes include adjudicated clinical fractures, remission of low-grade persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), progression from pre-diabetes to diabetes, correction of anemia, and overall sexual activity, sexual desire, and erectile function. This randomized, placebo-controlled trial offers an historical opportunity to advance our understanding of the cardiovascular safety and long-term efficacy of testosterone replacement in middle-aged and older hypogonadal men.

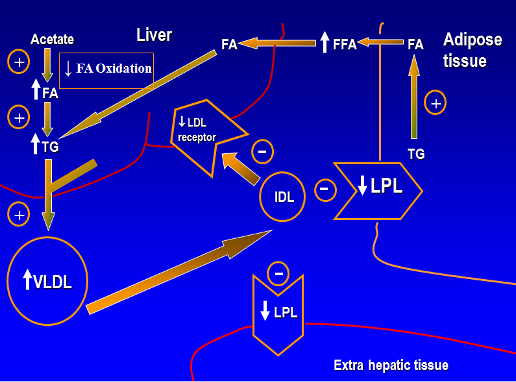

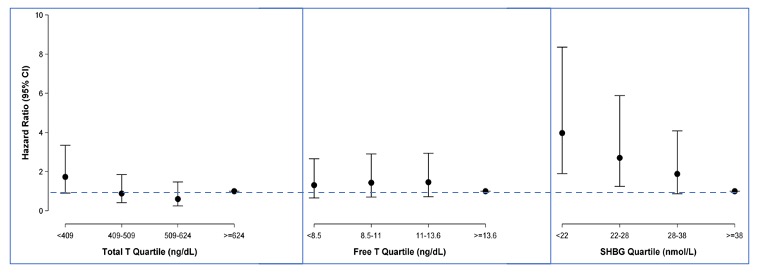

Testosterone levels are lower in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus compared with controls (505-510). Low total testosterone levels have been associated with lower insulin sensitivity (505,511) and increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome in community dwelling men both cross-sectionally and longitudinally (508-510,512-520). However, the association of free testosterone and type 2 diabetes mellitus has been inconsistent; some studies have reported a weak relationship (509,510,512) while others have failed to find any relationship (508,514). Circulating sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and some SHBG polymorphisms also have been associated negatively with the risk of type 2 diabetes (508-510,512-516,521-524). For instance, individuals with the rs6257and rs179994 variant alleles of the SHBG single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) have lower plasma SHBG levels and a higher risk of type 2 diabetes (521-524). Similarly, individuals with the rs6259 variant have higher SHBG levels and lower type 2 diabetes risk (524). We performed longitudinal analyses of men participating in the Massachusetts Male Aging Study (525), a population-based study of men aged 40-70 years (Figure 13) to evaluate whether SHBG is an independent predictor of T2DM (526). After adjustment for age, body mass index, hypertension, smoking, alcohol intake and physical activity, the hazard ratio for incident type 2 diabetes was 2.0 for each one SD decrease in SHBG and 1.29 for each one SD decrease in total testosterone (525). Free testosterone was not significantly associated with type 2 diabetes. The strong association of T2DM risk with SHBG persisted even after additional adjustment for free testosterone. The association of SHBG polymorphisms with type 2 diabetes suggests a potential role of SHBG in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. In a Mendelian randomization analysis of the UK Biobank data, genetically determined free testosterone levels were associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a sexually dimorphic manner after adjusting for SHBG levels; men with low genetically determined free testosterone levels had increased risk of type 2 diabetes while women with low genetically determined free testosterone levels had reduced risk of type 2 diabetes (527).

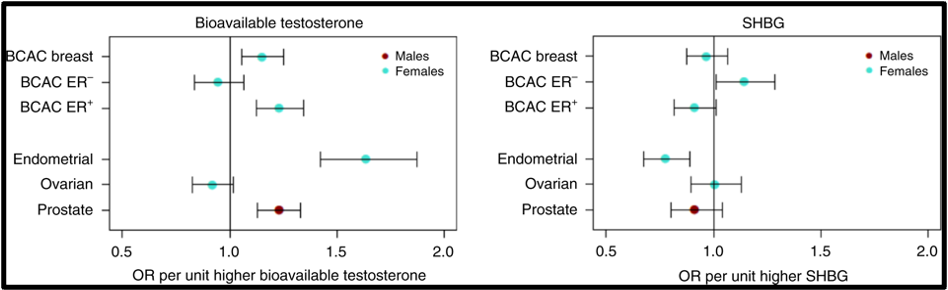

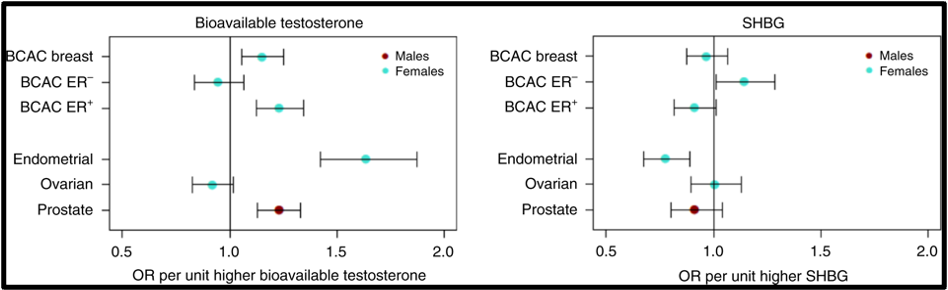

There is no evidence that testosterone causes prostate cancer (539). A retrospective analysis of the Registry of Hypogonadism in Men (RHYME) (540) and several meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (486,541,542) did not find an increased risk of prostate cancer in men receiving testosterone. Also, there is no consistent relationship between endogenous serum testosterone levels and the risk of prostate cancer (16,18,123,343,542-545). A meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies did not find a significant association between endogenous total testosterone levels and prostate cancer (542). Conversely, an analysis of 20 prospective studies found that men in the lowest tenth of free testosterone concentration had a lower risk of prostate cancer (OR=0.77, 95%CI= 0.69 to 0.86; p<0.001) compared with men with higher concentrations (545). Similarly, in the male participants in the UK Biobank followed for a mean of 6.9 years, higher genetically determined free testosterone was associated with a higher risk of prostate cancer, while total testosterone was not associated with prostate cancer risk (Figure 15) (546). The men with Klinefelter Syndrome have lower risk of prostate cancer than the general population. Taken together, these data suggest that life-long exposure to testosterone treatment in hypogonadal men could potentially increase the risk of prostate cancer.

Figure15. Mendelian Randomization: Genetically Determined Bio-Testosterone Associated with Increased Prostate Cancer Risk. Legend: UK Biobank Study: Genetic determinants of bioavailable testosterone were positively associated with risk of prostate cancer in men and ER+ breast cancer and endometrial cancer in women. Reproduced with permission from: Ruth KS, et al. Nat Med. 2020;26(2):252‐258.

Prostate cancer is an androgen–dependent tumor, and testosterone treatment is known to promote the growth of metastatic prostate cancer (544,547). Testosterone administration has been historically contraindicated in men with history of prostate cancer (16,543). The prevalence of subclinical, microscopic foci of prostate cancer in older men is high (548-555). There is concern that testosterone administration might make these subclinical foci of cancer grow and become clinically overt. In addition, older men with low testosterone levels may have prostate cancer (556,557). Morgentaler et al (556,557) reported a high prevalence of biopsy-detectable prostate cancer in men with low total or free testosterone levels despite normal PSA levels and normal digital rectal examinations. However, this study did not have a control group, and we do not know whether sextant biopsies of age-matched controls with normal testosterone levels would yield a similarly high incidence of biopsy-detectable cancer. Therefore, this study should not be interpreted to conclude that there is a higher prevalence of prostate cancer in older men with low testosterone levels, or that low testosterone levels are an indication for performing prostate biopsy.

Effects of Testosterone Therapy on Prostate Events

None of the testosterone trials in middle-aged or older men had sufficient power or intervention duration to detect meaningful differences in the incidence of prostate cancer between testosterone and placebo-treated men. Testosterone treatment of hypogonadal men increases PSA levels (16,558), which may lead to urological referral for prostate biopsy. A systematic review of randomized testosterone trials in middle-aged and older men found (413) that men treated with testosterone in clinical trials were at significantly higher risk for undergoing prostate biopsy than placebo-treated men (413). Because of the high prevalence of subclinical prostate cancer in older men, the higher number of prostate biopsies in testosterone-treated men could lead to increased detection rates of subclinical prostate cancer in comparison with placebo-treated men. Thus, testosterone therapy of middle-aged and older men is associated with a higher risk of prostate biopsy and a bias towards detection of a higher number of prostate events (18,413).

Administration of exogenous testosterone or suppression of circulating levels of testosterone by administration of a GnRH antagonist is not associated with proportionate changes in intra-prostatic testosterone or DHT concentrations. For instance, in a randomized controlled trial, Marks et al (559) measured intraprostatic testosterone and DHT levels in older men treated with placebo or testosterone. Surprisingly, intraprostatic DHT concentrations were not significantly higher in testosterone-treated men than in placebo-treated men (559). Similarly, the expression levels of androgen-dependent genes in the prostate were not significantly altered by testosterone administration (559). In separate studies, lowering of circulating testosterone levels by administration of a GnRH antagonist was not associated with changes in intraprostatic androgen concentrations (560,561).

Effects of Testosterone Replacement on Serum PSA Levels

Serum PSA levels are lower in androgen–deficient men and are restored to normal following testosterone replacement (16,558,562-570). Lowering of serum testosterone concentrations by withdrawal of androgen therapy in young, hypogonadal men is associated with a decrease in serum PSA levels. Similarly, treatment of men with benign prostatic hyperplasia with a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor, finasteride, is associated with a significant lowering of serum and prostatic PSA levels (570,571). However, serum PSA levels do not increase progressively in healthy hypogonadal men with replacement doses of testosterone. The increase in PSA levels during testosterone replacement might trigger evaluation and biopsy in some patients (16,543).

More intensive PSA screening and follow-up of men receiving testosterone replacement might lead to an increased number of prostate biopsies and the detection of subclinical prostate cancers that would have otherwise remained undetected (16,543). Serum PSA levels tend to fluctuate when measured repeatedly in the same individual over time (572-574). There is considerable test-retest variability in PSA measurements (572-574). Some of this variability is due to the inherent assay variability, and a significant portion of this variability is due to unknown factors. Fluctuations are larger in men with high mean PSA levels. Variability can be even greater if measurements are performed in different laboratories that use dissimilar assay methodology (572-574).

An important issue is what increment in PSA level should warrant a prostate biopsy in older men receiving testosterone replacement. To address this issue, we conducted a systematic review of published studies of testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men (543). This review indicated that the weighted effect size of the change in PSA after testosterone replacement in young, hypogonadal men is 0.68 standard deviation units (95% confidence interval 0.55 to 0.82). This means that the effect of testosterone replacement therapy is to increase PSA levels by an average 0.68 standard deviations over baseline. Because the average standard deviation was 0.47 in this systematic analysis, the standard deviation score of 0.68 translates into an average increase in serum PSA levels of about 0.30 ng/ml in young hypogonadal men (543). The average change in serum PSA levels after testosterone replacement in studies of older men was 0.43 ng/mL (543). The data from the Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study (PLESS) demonstrated that the 90% confidence interval for the change in PSA values measured 3 to 6 months apart is 1.4 ng/mL (570). Therefore, a change in PSA of >1.4 ng/ml between any two values measured 3 to 6 month apart in the same patient is unusual (16,543). In the TTrials, 2.4% of men receiving testosterone had increases above 1.4 ng/mL at 3 months, and 4.7% at 12 months (26).

Carter et al, based on the analysis of PSA data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, reported that PSA velocity, defined as the annual rate of change of PSA, is different in men who develop prostate cancer than in those who do not (575-577). Thus, PSA velocity greater than 0.7 ng/ml/year was unusual in men without prostate cancer whose baseline PSA was between 4 and 10 ng/ml (575-577). However, most men being considered for testosterone replacement will have baseline PSA less than 4 ng/ml. In a subsequent analysis, the same group reported that the PSA velocity in men with baseline PSA between 2 and 4 ng/ml was 0.2 ng/ml/year (577). Because test-to-retest variability in PSA measurement is far greater than this threshold, it is likely that the use of this threshold of 0.2 ng/ml/year to select men for prostate biopsy would lead to many unnecessary biopsies.

In eugonadal, young men, administration of supraphysiological doses of testosterone does not further increase serum PSA levels (166,169,578). These data are consistent with dose response studies in young men that demonstrate that maximal serum concentrations of PSA are achieved at testosterone levels that are at the lower end of the normal male range; higher testosterone concentrations are not associated with higher PSA levels (166,169).

In summary, these data suggest that the administration of replacement doses of testosterone to androgen-deficient men can be expected to produce a modest increment in serum PSA levels. Increments in PSA levels after testosterone supplementation in androgen-deficient men are generally less than 0.5 ng/mL and increments in excess of 1.4 ng/mL over a 3–6-month period are unusual. Nevertheless, administration of testosterone to men with baseline PSA levels between 2.6 and 4.0 ng/mL will cause PSA levels to exceed 4.0 ng/mL in some men. Increments in PSA levels above 4 ng/mL will trigger a urological consultation and many of these men will be asked to undergo prostate biopsies. However, considering the controversy over prostate cancer screening and monitoring, the decision to monitor PSA levels during testosterone treatment and the decision to refer a patient for consideration of prostate biopsy should be made only after informing him of the risks and benefits of prostate cancer screening and monitoring and engaging the patient in a shared decision-making process.

Monitoring PSA Levels in Older Men Receiving Testosterone Replacement (Tables 3 and 4)

Older men considering testosterone supplementation should undergo evaluation of risk factors for prostate cancer; the Endocrine Society guideline suggest a baseline PSA measurement and a digital prostate examination (16). Prostate cancer screening has some risks; therefore, initiation of prostate monitoring should be a shared decision, made only after a discussion of the risks and benefits of prostate cancer monitoring. Men with history of prostate cancer, should not be given androgen supplementation and those with palpable abnormalities of the prostate or PSA levels greater than 3 ng/ml should undergo urological evaluation. After initiation of testosterone replacement therapy, PSA levels should be repeated at 3 months and annually thereafter (16). Although measurements of free PSA and PSA density have been proposed to enhance the specificity of PSA measurement, long term data, especially from studies of testosterone replacement in older men, are lacking. Considering the interassay variability and the longitudinal change in PSA previously discussed, an Endocrine Society Expert Panel recently suggested that men receiving testosterone replacement should be referred to urological consultation if: 1) PSA increases more than 1.4 ng/mL in the first 12 months of treatment; 2) a PSA above 4 ng/mL is confirmed; or 3) a prostatic abnormality is detected on digital rectal examination (16). After 12 months of treatment, prostate monitoring should follow standard guidelines for prostate cancer screening taking into account the age and race of the patient (16).

|

Table 3. Recommendations for Monitoring of Men Receiving Testosterone Therapy

|

|

A. Explain the potential benefits and risks of monitoring for prostate cancer and engage the patient in shared decision making regarding the prostate monitoring plan.

|

|

B. Evaluate the patient at 3–12 months after treatment initiation and then annually to assess whether symptoms have responded to treatment and whether the patient is suffering from any adverse effects

|

|

C. Monitor testosterone concentrations 3–6 months after initiation of therapy:

· --Therapy should aim to raise testosterone into the mid-normal range.

· --Injectable testosterone enanthate or cypionate: measure testosterone midway between injections. If midinterval T is >600 ng/dL (24.5 nmol/L) or <350 ng/dL (14.1 nmol/L), adjust dose or frequency.

· --Transdermal gels: assess testosterone 2–8 h following the gel application, after the patient has been on treatment for at least 1 week; adjust dose to achieve testosterone in the mid-normal range.

· --Transdermal patches: assess testosterone 3–12 h after application; adjust dose to achieve concentration in the mid-normal range.

· --Buccal T bioadhesive tablet: assess concentrations immediately before or after application of fresh system.

· --Testosterone pellets: measure concentrations at the end of the dosing interval. Adjust the number of pellets and/or the dosing interval to maintain serum T concentrations in the mid-normal range.

· --Oral T undecanoate: monitor serum T concentrations 3–5h after ingestion with a fat-containing meal.

· --Injectable testosterone undecanoate: measure serum T levels at the end of the dosing interval just prior to the next injection and aim to achieve nadir levels in low-mid range.

|

|

D. Check hematocrit at baseline, 3–6 months after starting treatment, and then annually. If hematocrit is >54%, stop therapy until hematocrit decreases to a safe level; evaluate the patient for hypoxia and sleep apnea; reinitiate therapy with a reduced dose.

|

|

E. Measure BMD of lumbar spine and/or femoral neck after 1–2 year of testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men with osteoporosis, consistent with regional standard of care.

|

|

F. For men 55–69 years of age and for men 40–69 years of age who are at increased risk for prostate cancer who choose prostate monitoring, perform digital rectal examination and check PSA level before initiating treatment; check PSA and perform digital rectal examination 3–12 months after initiating testosterone treatment, and then in accordance with guidelines for prostate cancer screening depending on the age and race of the patient.

|

|

G. Obtain urological consultation if there is:

· An increase in serum PSA concentration.1.4 ng/mL within 12 months of initiating testosterone treatment

· A confirmed PSA > 4 ng/mL at any time

· Detection of a prostatic abnormality on digital rectal examination

· Substantial worsening of lower urinary tract symptoms

|

Adapted with permission from the Endocrine Society Guideline for Testosterone Therapy in Men with Hypogonadism in: Bhasin et al J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103(5):1715-1744.

|

Table 4. Indications for Urological Consultation in Men Receiving Testosterone Replacement

|

|

1. 1) An increase in serum or plasma PSA concentration >1.4 ng/mL within any 12-month period after initiating testosterone treatment

|

|

2. 2) A PSA >4.0 ng/mL

|

|

3. 3) Detection of a prostatic abnormality on digital rectal examination

|

|

4. 4) An AUA/IPSS prostate symptom score of >19

|

Adapted with permission from the Endocrine Society Guideline for Testosterone Therapy in Men with Hypogonadism in: Bhasin et al J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103(5):1715-1744.

Testosterone and Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy

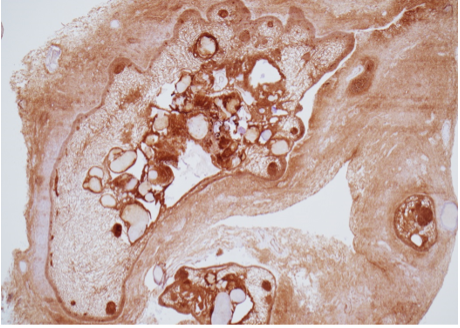

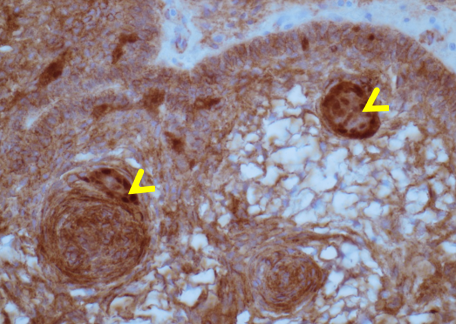

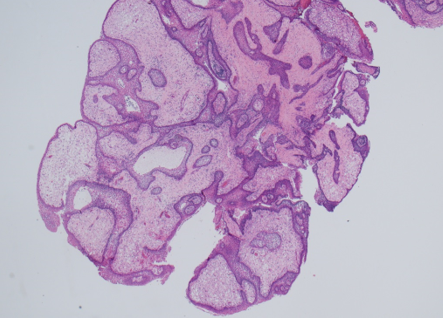

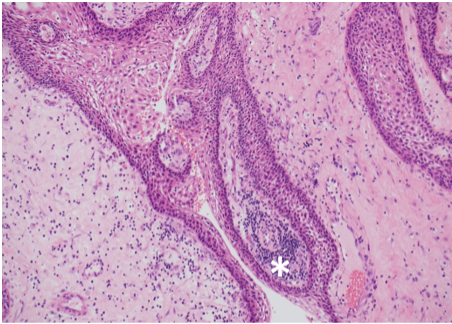

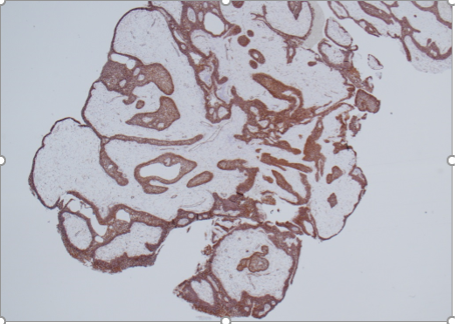

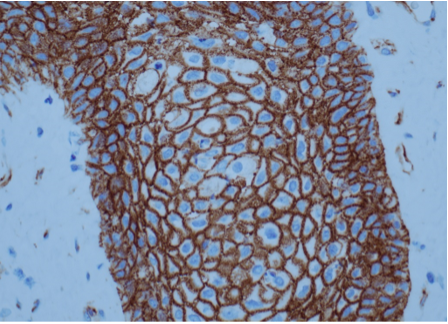

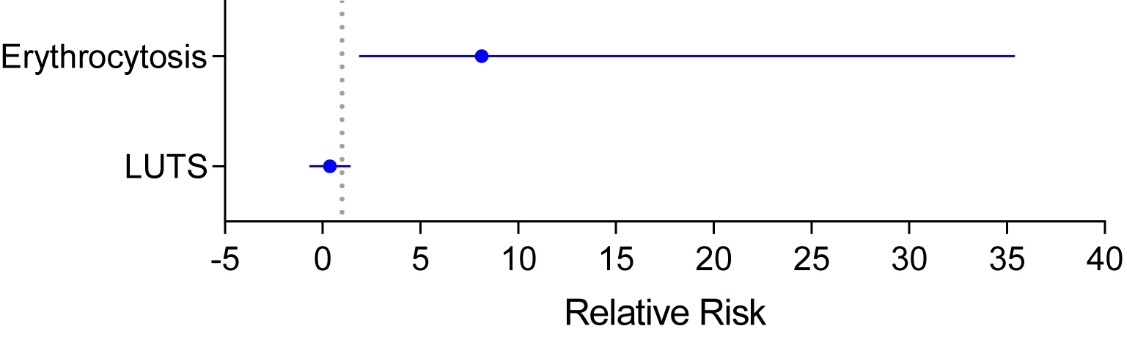

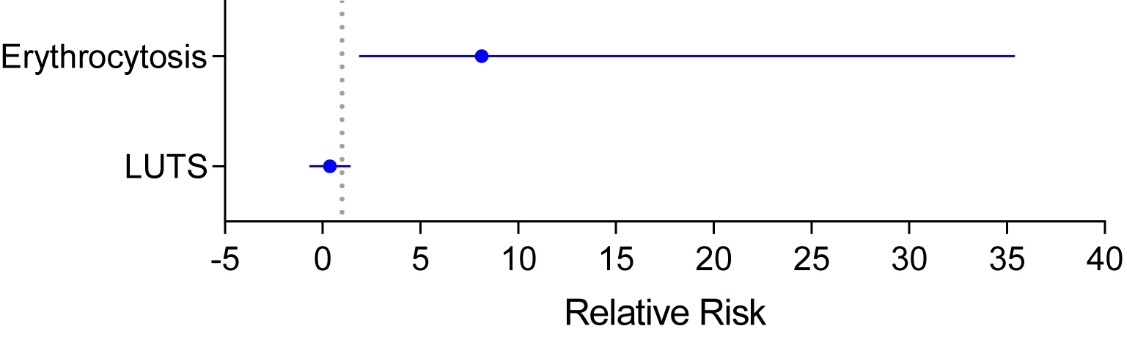

Testosterone replacement can be administered safely to men with benign prostatic hypertrophy who have mild to moderate symptom scores. The severity of symptoms associated with benign prostatic hypertrophy can be assessed by using either the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) or the American Urological Association (AUA) Symptom questionnaires. Androgen deficiency is associated with decreased prostate volume and androgen replacement increases prostate volume compared to age–matched controls (559,562,566,567). Meta-analyses of testosterone trials have not found statistically significant difference in lower urinary tract symptoms scores in hypogonadal men receiving testosterone replacement compared to placebo (Figure 16) (256,579). However, in patients with pre–existing, severe symptoms of benign prostatic hypertrophy, even small increases in prostate volume during testosterone administration may exacerbate obstructive symptoms. In these men, testosterone should either not be administered or administered with careful monitoring of obstructive symptoms.

Figure 16. Adverse events associated with testosterone therapy in randomized trials. The relative risk and 95% CI for development of erythrocytosis (RR= 8.14; 95%CI= 1.87 to 35.40) and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS; RR= 0.38; 95%CI= -0.67 to 1.43) in randomized testosterone trials derived from meta-analyses published by Ponce et al., 2018 are shown. The figure was adapted with permission from Ponce et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(5):1745-54.

ERYTHROCYTOSIS

Testosterone replacement is associated with increased red cell mass and hemoglobin levels (Figure 16) (256,329,580-585). Therefore, testosterone replacement should not be administered to men with baseline hematocrit of 52% or greater without appropriate evaluation and treatment of erythrocytosis (16) (Table 3). Administration of testosterone to androgen–deficient young men is typically associated with a small increase in hemoglobin levels. Clinically significant erythrocytosis is uncommon in young hypogonadal men during testosterone replacement therapy, but can occur in men with sleep apnea, significant smoking history, or chronic obstructive lung disease. Testosterone administration in older men is associated with greater increments in hemoglobin than observed in young, hypogonadal men (321). The magnitude of hemoglobin increase during testosterone therapy appears related to the testosterone dose, the increase in testosterone concentrations during testosterone therapy, and age (321). Testosterone replacement by means of a transdermal system has been reported to produce a lesser increase in hemoglobin levels than that associated with intramuscular testosterone enanthate and cypionate presumably because of the substantially higher testosterone dose and average circulating testosterone levels achieved with testosterone esters (586).

Testosterone increases hemoglobin and hematocrit by multiple mechanisms (322,408,409,587). Testosterone administration stimulates iron-dependent erythropoiesis by suppressing hepcidin transcription and increasing iron availability for erythropoiesis (322,408,409,587). Additionally, testosterone stimulates erythropoiesis by a direct effect on bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors and increasing the numbers of myeloid progenitors. Testosterone also stimulates erythropoietin and alters the set-point of the relationship between erythropoietin and hemoglobin (322). Testosterone supplementation can correct anemia in older men with unexplained anemia of aging and anemia of inflammation (322,329,409). Suppression of testosterone secretion in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy reduces hematocrit and hemoglobin levels by slowing erythropoiesis independently of changes in erythropoietin levels (588).

Monitoring Hematocrit During Testosterone Replacement Therapy (Table 3)

Hematocrit levels should be measured at baseline and 3 months after institution of testosterone replacement or after increase in dosage, and every 12 months thereafter. It is not clear what absolute hematocrit level or magnitude of change in hematocrit warrants discontinuation of testosterone administration. Plasma viscosity increases disproportionately as hematocrit rises above 50%. Hematocrit levels above 54% may be associated with increased risk of neuro-occlusive events. Therefore, testosterone dose should be withheld if hematocrit rises above 54%; once hematocrit falls to a safe level, testosterone therapy may be re-initiated at a reduced dose or with a different formulation (16).

SLEEP APNEA

Circulating testosterone concentrations are related to sleep rhythm and are generally higher during sleep than during waking hours (589-592). Testosterone secretory peaks coincide with the onset of rapid-eye movement sleep. Aging is associated with decreased sleep efficiency, reduced numbers of REM sleep episodes, and altered REM sleep latency, which may contribute to lower circulating testosterone concentrations (590-594). The degree of sleep-disordered breathing increases with age and is associated with reduced overnight plasma bioavailable testosterone. Thus, changes in sleep efficiency and architecture are associated with alterations in testosterone levels in older men (590-594). Sleep apnea and disordered sleep are often associated with low testosterone levels (595), particularly in patients with more severe cases of OSA (i.e. severe hypoxemia) (596). Some potential mechanisms by which OSA may decrease endogenous testosterone levels include disruption of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion from restricted sleep and/or recurrent nocturnal hypoxia (597,598), which is further exacerbated by obesity. OSA treatment with continuous positive airway pressure has been demonstrated to increase serum testosterone levels (599).

Testosterone can induce or exacerbate sleep apnea in some individuals, particularly those with obesity or chronic obstructive lung disease (589-594,600). This appears to be due to direct effects of testosterone on laryngeal muscles. Testosterone administration depresses hypercapnic ventilator drive and induces apnea in primate infants (594). Short-term administration of high doses of testosterone shortens sleep duration and worsens sleep apnea in older men (601). The frequency of sleep apnea in randomized testosterone trials in older men has been very low (16,486) and no randomized trial has reported an increased incidence of OSA or OSA worsening in men randomized to the testosterone arm compared to the placebo arm.

Testosterone should not be given to men with severe untreated OSA without evaluation and treatment of sleep apnea. Several screening instruments can be used to detect sleep apnea. A history of loud snoring, and daytime somnolence, in an obese individual with hypertension increases the likelihood of having sleep apnea; such patients should be referred for a sleep study.

BREAST ENLARGEMENT AND TENDERNESS