ABSTRACT

Men continue to have a strong interest and commitment to effective family planning. Traditional methods of male contraception have long included periodic abstinence, non-vaginal ejaculation, condoms, and vasectomy, the latter two representing physical methods to prevent sperm from reaching the site of fertilization. However, for male contraception the reversible methods are not reliable, and the only reliable method, vasectomy, is not intended as reversible. During the 20th century, a wide array of reversible and highly reliable female hormonal contraceptive methods was marketed; however, no new methods for male fertility regulation have been introduced for centuries. For men to share more equally the burdens as well as the benefits of family planning, more effective reversible male contraceptive methods need to be available. Most studies into male contraception have been conducted with hormonal methods, analogous to well-known female hormonal contraceptives, making them the closest to introducing a reliable, reversible male contraceptive method. The most promising hormonal approach is the combination of an androgen (usually testosterone) with a progestin and multiple studies have shown such combinations of depot steroids displays high contraceptive efficacy, based on reliable and reversible suppression of sperm output, with few side effects. While research into novel methods for male fertility regulation has continued in the public sector, private sector research into male contraception, essential for effective commercial product development, has stalled in recent decades.

BACKGROUND

A male contraceptive must reduce the number of fertile sperm ejaculated into the vagina to levels that reliably prevent fertilization (1). Conception can be prevented by diverting or suppressing sperm output and/or inhibiting sperm fertilizing capacity. So far, all male methods depend on mechanical means to reduce female exposure to sperm using either traditional drug and device-free methods (abstinence, withdrawal, non-vaginal intercourse) or contemporary male methods comprising condoms and vasectomy. Unfortunately, among current male contraceptive options, the reversible methods are not reliable, and the reliable method is not intended as reversible. No new male contraceptive methods were introduced during the 20th century contrasting with highly reliable, reversible hormonal contraceptives developed for women over the last half century. Yet male involvement in family planning remains extensive. Globally, one third of couples using contraception rely on methods requiring active male participation (2) and current male methods remain (together with medicated intrauterine devices) the most cost-effective contraceptive methods in the USA (3). While reflecting traditional and ongoing reliance of family planning on male involvement, greater participation by men in sharing the burdens as well as the benefits of effective family planning require developing more effective, reversible male methods. Such greater participation could ameliorate the still large unmet need for contraception globally as 40% of pregnancies are still unintended with half of unintended pregnancies ending in abortion and those rates are higher among developed countries (4). Family planning must always remain a matter of personal choice by couples. This is highlighted by the human rights abuses of coercive national family planning programs enforcing family limitation (“one-child family”), including through forced sterilization and abortion, in India and China (5, 6). Such coercive national programs originated in the 1970’s prompted by uncritical belief in the “population explosion”, notably from influential publications such as the Club of Rome’s “Limits to Growth” and Ehrlich’s “Population Bomb”, now discredited by their failed, alarmist predictions. India’s forced sterilization program was overturned by popular democratic action within a few years of its imposition whereas China’s one-child family policy operated for nearly 4 decades before its ending in 2016. These issues echo in medical mistrust as a barrier to acceptance of male contraception among the Black American minority (7).

Extensive public sector clinical research over the last 4 decades (8), despite minimal pharmaceutical industry involvement, has proven in principle that hormonal male contraception is feasible. Proof-of-principle is established for androgen-based hormonal suppression of spermatogenesis (9) achieving full reversibility (10), sufficient short-term safety (11) and acceptability to men and women (12, 13) culminating in the crucial proof of reliable contraceptive efficacy using androgen alone (14-17) or depot (18) or daily use (19) androgen-progestin combinations. Demographic modelling shows that introducing new male contraceptive methods, even if adopted by only a minority of men, would significantly reduce unintended pregnancies in Nigeria, South Africa, and the USA (20). Surveys of participants in clinical male contraceptive studies suggest that men may prefer a male contraceptive to be provided by their family doctor rather than specialists (21); however, the practical knowledge of non-specialists remains unsatisfactory and would require specific training (22). In addition to boutique contraception for adventurous early adopters, practical niches for male contraception include contraception after birth, during breast-feeding, or after abortion (23). Nevertheless, despite the proof-of-principle, strong community interest, and medical priority on the need for new, reversible male contraceptives, pharmaceutical industry development has ceased. This market failure reflects pharmaceutical industry perceptions of low profitability coupled with high risk in the context where a better return on investment is expected for developing drugs in more lucrative, less risky areas of chronic disease compared with the higher product liability risk of developing novel contraceptives for healthy men to compete with existing low-cost female methods. The possibility that Western market failure might be overcome if the growing perception of needs for voluntary family planning as a national priority in rapidly industrializing countries such as China, India and Brazil (24), has proved a failed hope. Novel approaches to finance further research such as philanthropic private sector funding (25) and public-private partnerships (26) have been developed. The 2022 overturning by the US Supreme Court of what was long accepted as a constitutional right to abortion has refreshed interest in developing wider coverage of effective contraception, including for men, to reduce the demand for abortion.

NON-HORMONAL METHODS

Traditional Methods

PERIODIC ABSTINENCE

Although theoretically effective, neither celibacy nor castration is an acceptable or practical contraceptive method. Periodic abstinence, the limiting of sexual intercourse to "safe" days (27), has high contraceptive efficacy if the rules are followed perfectly but the failure rates rise steeply with rule breaking (28). This cost- and device-free method is used by >40 million couples world-wide for family planning (2). The typical use 1st year failure rate is ~25% with ~47% of couples continuing use at 1 year in USA (29) but 8% and 52%, respectively, in France (30, 31). While inherently safe, it has limited acceptability due to low reliability, inflexibility, and interference in the spontaneity of sex.

EX-VAGINAL EJACULATION

Withdrawal is a traditional male method of contraception whereby intercourse culminates in extra-vaginal ejaculation (32). Often overlooked as a contraceptive method, withdrawal, together with abortion, was the major pre-industrial method of family planning largely responsible for the demographic transition from high to relatively low birth rates in industrial nation states and continues to be used by 40 million couples (2). This cost- and device-free method has limited reliability in its demanding requirement for skill and self-control. The typical use 1st year failure rate is 18-22% with 46% continuing use at 1 year in the USA (29, 33) and 10% and 55%, respectively, in France (30, 31). While safe and reasonably effective for experienced users, interfering with the pleasure of coitus leads to a correspondingly high failure rate in practice. Other sexual practices that avoid intravaginal ejaculation have also been used traditionally to avoid conception. These include masturbation, oral and anal intercourse, deliberate anejaculation and retrograde ejaculation (34).

CONDOM

After centuries of use in preventing sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy, now over 50 million couples rely on condoms for contraception (2). Condoms provide safe, cheap, widely available, user-controlled, and reversible contraception with few side-effects. In case of latex allergy, non-rubber (polyurethane, natural membrane) condoms can be substituted. Latex condoms are moderately effective at preventing pregnancy with a typical 1st year failure rate of 18% with 43% continuing use at 1 year in the USA (29, 33) and 3.3% and 47%, respectively, in France (30, 31). Recent US data suggest a reduction in failure rate to 13% (35). The discrepancy from the estimated 2% perfect-use failure rate (29) is mainly to human error, notably rushed use (36), misuse, or non-use rather than mechanical failure (breakage or slippage) (37). Differences in contraceptive use behaviors may explain lower reported 1st year failure rates for condoms in France (31). The major limitations of condoms for contraception are relatively high failure rates and interference with sexuality. The requirement for regular and correct application during foreplay disturbs the spontaneity of sex and dulls erotic sensation. These aesthetic drawbacks limit the popularity of condoms especially among stable couples (38). Latex condoms are perishable through tears or snagging on fingernails, clothing, or jewelry as well as deterioration from exposure to light, heat, humidity, or organic oils.

Polyurethane condoms with improved tactile sensitivity were developed in the 1990’s to enhance acceptability (39), but they have shown reduced efficacy and mechanical performance compared with latex condoms in prospective randomized controlled clinical trials (40). Although the theoretical requirements for condom use to protect against sexually transmitted infections differ from those to prevent pregnancy, in practice the protections are similar (41). Laboratory testing of condoms standardizes integrity and durability for strength and leakage. Although viral penetration is not routinely tested, synthetic (latex or polyurethane) but not natural membrane condoms are not perfect at preventing passage of prototype human pathogenic viruses (42). Using a sensitive, objective biochemical marker (PSA) for seminal plasma exposure in vaginal swabs, vaginal exposure to semen was reduced by 50-80% even after mechanical condom failure (breakage, slippage) (43). Novel spermicides with virucidal properties that are being developed to provide dual antimicrobial and contraceptive protection (44) might not enhance condom efficacy for either function because non-compliance is the major cause of failure for both (37).

VASECTOMY

Vasectomy, used by over 40 million couples for family planning (2), varies widely in prevalence between countries depending upon cultural factors, public education, and availability of male-oriented facilities (45). Recent data suggests a steady decline in vasectomy in the US over the first two decades of the 21st century (46). Having overcome a sordid history of applications to eugenics and other historical misadventures into the 20th century (47), vasectomy is now more widely used than female sterilization in some economically developed countries although female sterilization remain ~4 times more frequent worldwide (48). For men having completed their family and fit for minor surgery, vasectomy is a very safe and highly effective office procedure (49, 50). Relative contraindications include risks from office-type surgery (bleeding disorders, allergy to local anesthetic) or scrotal pathology (post-inguinal surgery scarring, keloid-proneness, active genitourinary or groin infections). Vasectomy is performed under local anesthesia via scrotal incisions and usually involves excising a segment of both vasa deferentia. Interposing a fascial barrier between the occluded cut ends significantly reduces the risk of failure due to recanalization (51, 52). The Chinese-developed "no-scalpel" technique (53)minimizes skin incision and reduces immediate side-effects (bleeding, infection) 10-fold to 0.3% compared with conventional vasectomy (54, 55). Chronic post-vasectomy pain (56) occurs with an estimated prevalence of ~15% at 7 months after vasectomy (57). It may be reported as groin or testicular pain precipitated or aggravated by intercourse, ejaculation, or exertion and accompanied by tender, distended epididymides (56, 57). Fascial interposition significantly reduces failure rate (52, 58) so that, in the hands of an experienced practitioner, no-scalpel vasectomy with fascial interposition is now the method of choice (55, 59). Additional studies suggest that cautery may further enhances reliability (60, 61) and that leaving an open testicular end reduces retrograde pressure-related complications (pain, sperm granuloma, epididymal and testicular damage) thereby better preserving reversibility (62-64).

Vasectomy is highly effective once sperm are cleared from the distal vasa deferentia. However, flushing with saline or water (65-69) or spermicides (nitrofurazone (70), euflavine (71, 72) or chlorhexidine (73)) during surgery does not accelerate sperm clearance, but the evidence remains weak (74). Non-irritant spermicides that inhibit sperm function without chemical sclerosis of the vasa that would impair potential reversibility, might have promise (75). Immediately following vasectomy, additional contraception must continue until azoospermia or near azoospermia (<0.1 million non-motile sperm per mL) is demonstrated usually at 3 months post-vasectomy when at least 95% of men reach this clearance criterion (76-79). Although azoospermia might occur sooner (80), reliable evidence is lacking to support the reliability of earlier time points as recanalization, where motile sperm persist in the ejaculate, may occur within the first few weeks after vasectomy (81) and persistence of motile sperm in the ejaculate indicates technical failure. Although detailed information on the rate of sperm clearance from the ejaculate after vasectomy remains sparse, time since vasectomy rather than number of ejaculations is more predictive of sperm clearance (80). Contraceptive failures are rare; early failures are most often due to not awaiting sperm clearance (82) or occasionally misidentification or duplication of the vasa deferentia whereas late failures are due to spontaneous vas(a) recanalization (~0.1%) (83). Complications of vasectomy include post-surgical bleeding, wound or genito-urinary infections and fistulae, and chronic scrotal pain (50, 84) with risk of death estimated at ~1 per million vasectomies in developed countries although higher in developing countries (85). Vasectomy causes no consistent changes in circulating hormones (86), sexual function, or risk of cardiovascular or other diseases (49, 87, 88) including testicular cancer (89-91). A small increased risk of prostate cancer after vasectomy has been observed in case-control studies (92-94), but the increased risk is unaffected by vasectomy reversal (95, 96). This risk seems to be attributable to surveillance and detection bias, rather than a biological effect as indicated by consistent evidence from numerous cohort studies (96-102). Sperm antibodies develop in most vasectomized men but have no known deleterious health effects apart from a possible role in reducing fertility after vasectomy reversal (103) when sperm antibody titers are very high (>512) (104).

Vasectomy is a quick, simple, highly effective, and convenient method of permanent sterilization; its major drawback as a male contraceptive is its limited reversibility. Elective sperm cryostorage is occasionally useful but may reflect ambivalence about the irreversible intent of vasectomy. Cumulative rate of requests for reversal, mostly prompted by remarriage, are 2.4% at 10 year post-vasectomy but exceed 10% for young men (aged <25 years at vasectomy) (105). Failed vasectomy reversal is now a significant cause of male infertility. Following microsurgical vasovasostomy, 80-100% have any sperm in the ejaculate ("patency") but normal sperm concentration is less common, and cumulative conception rate at 12 months is only ~50% compared to 80-85% at 12 months in healthy young couples not using contraception (105). This discrepancy is most probably attributable to technical limitations of microsurgery as even the lowest reported rates of azoospermia (bilateral non-patency) after microsurgical vasovasostomy indicate that nearly half such men have at least one non-patent vas deferens (106) so that re-operation should be a prominent consideration if pregnancy does not ensue. After technical failure, the wife’s age and time since vasectomy appear to be the dominant predictors of successful reversal (107, 108) Whether robotic microsurgery can improve the technical success of vasovasostomy to become a cost-effective and widely available alternative to human microsurgery remains to be established (109-111). Reversibility is better with microsurgery (106), presence of sperm in the vasal fluids from testicular end of stump (112), in younger men with shorter duration since vasectomy (105) and possibly with longer testicular vasal stump (113, 114); unfavorable predictors include non-microsurgical techniques, older age of wife (especially after 40 yr) (106, 115), high titers of sperm antibodies (104), and long duration (>10 years) since vasectomy (116-118) due to long-term epididymal (119), vasal (120) and testicular damage (116, 117, 121, 122). Experimentally in a variety of mammalian species, open-ended vasectomy is preferable to complete vas occlusion in preventing the back pressure-induced damage to spermatogenesis and seminiferous tubular integrity which are important contributors to failure of vasectomy reversal (123, 124). An alternative to surgical vasectomy reversal either instead of, or after failed vaso-vasostomy, is sperm harvesting from epididymis or testis in conjunction with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)/in-vitro fertilization. Currently cost-benefit analyses suggest that microsurgical vaso-vasostomy is more cost-effective and safer in both North America (125) and Europe (126), with the wife’s age being a key determinant (107). However, optimal management depends on local clinical expertise as well as access to microsurgery and reproductive technologies. The feasibility of successful vasectomy reversal has led to the proposal that, although vasectomy is intended as permanent, some individuals may consider it a reversible contraceptive method (127). USA national economic indicators strikingly influence rates of vasectomy and of vasectomy reversal, which are increased and decreased, respectively, according to the unemployment rate and personal income (128); whether this applies in countries with national health schemes that reduce financial limitations on access to elective health care remains unknown.

Modern Methods

VAS OCCLUSION

The efficacy, safety, simplicity, and acceptability of vasectomy suggest that a reversible mechanical method of vasa occlusion would be an attractive male contraceptive option. Since vasectomy reversal is neither cheap nor widely available, more reversible vasa occlusion methods are needed (129). A nonsurgical, potentially reversible technique involving percutaneous injections of polymers that harden in-situ to form occluding plugs which might be later removed to restore fertility was reported (130) but, despite preliminary positive findings (131), formal evaluation showed vasa occlusion had lower efficacy (inducing azoospermia) than vasectomy (132). In a phase II randomized clinical trial, urethane-coated nylon thread intra-vasa devices were more acceptable with fewer complications but were less effective in producing azoospermia, compared with no-scalpel vasectomy (133). A hydrophilic gel, composed of co-polymer of styrene and maleic anhydride delivered in dimethyl sulfoxide, forms a charged spermicidal biopolymer when injected into the vas deferens that is stable but potentially removable. Experiments in rats favor sodium bicarbonate over dimethyl sulphoxide for intravasal injection for effective reversal of occlusion (134). Preliminary non-comparative clinical evaluation showed azoospermia in 12 men with no pregnancies in their wives for 12 months following intravasal injection suggesting effective vasal occlusion (135); however, some morphologically damaged and non-functional sperm persist in the ejaculate (136) but the mechanisms of the deleterious effects on sperm structure and function remain unexplained(137). In an extended multi-center phase III study of 139 fertile married men who had a single, bilateral intravasal injection of a styrene maleic anhydride copolymer in 120 µl of dimethyl sulphoxide solution (Reversible Inhibition of Sperm under Guidance, RISUG) were followed for six months after injection. In six men, the injections failed to be delivered, but in the remainder, 110 achieved azoospermia within 1 month and 23 achieved azoospermia 3 to 6 months after the procedure. After ceasing condom use in the first 2 months after injection, there were no pregnancies in the 133 men with successful occlusion over the next 4 months whereas pregnancies were reported in two of six men who had failed injections; however, reversibility was not reported (138). Another phase III randomized controlled clinical trial has shown that a prototype implantable non-occlusive intra-vasal device, comprising a nylon thread encased in barium-impregnated polyurethane, is as effective for sterilization as standard no-scalpel sterilization with no more adverse effects (139); however the reversibility of this device remains to be demonstrated. A promising development for a reversible vas occlusion is a solution for transcutaneous intravasal injection which forms a hydrogel in the vas to reversibly occlude it. The injection solution, comprising sodium alginate conjugated with thioketal and including titanium dioxide and calcium chloride, transforms after injection into the vas deferens into an occluding hydrogel. Subsequently, the occluding hydrogel can be cleared in vivo by non-invasive application of ultrasound that generates reactive oxygen species in the hydrogel causing cleavage of the thioketal and recanalizing the vas deferens. Experimental studies in rats demonstrated fully effective contraception and reversibility (140). Other technical developments including percutaneous injection of sclerosants and transcutaneous delivery of physical agents (ultrasound, lasers) continue to be developed slowly (141).

HEATING

It has long been known (142) that even brief elevations of testicular temperature can profoundly suppress spermatogenesis (143) while sustained elevation may contribute to testicular pathology in cryptorchidism, varicocele, and occupational male infertility (144). A highly novel experimental approach has been reported using intravenously injected iron oxide nanoparticles that accumulate in the testis where they can be activated by an external alternating magnet field to generate testicular heating and damage to spermatogenesis (145); however, safe clinical application, and notably reversibility, remain to be demonstrated. Clinical studies evaluating the potential for tight scrotal supports as a practical male contraceptive method (146, 147) showed a reversible decrease in sperm output but of inadequate magnitude for reliable contraception. Experience of small numbers of men utilizing thermal male contraception has been favorable, apart from discomfort (148) but wider uptake would require substantial population education (149). Given the dubious acceptability and safety (150) of heat-induced suppression of sperm output, the feasibility of a male contraceptive method based on testicular heating remains to be established.

IMMUNOCONTRACEPTION

Sperm vaccines to interrupt fertility have long been of interest (151) with a 1937 patent issued for vaccination with semen (152). Sperm express unique epitopes within the immunologically protected adluminal compartment of the seminiferous tubules at puberty, long after the definition of immune self-tolerance hence explaining their potential autoimmunogenicity. Sperm autoimmunity may contribute to subfertility after vasectomy reversal and in ~7% of infertile otherwise healthy men (other than orchitis). Experimental models for an effective multivalent chimeric protein sperm vaccine targeting surface-expressed antigens involved in fertilization have been reported (153) but remain untested in men. Practical application of this method requires resolving problems of the millions of sperm ejaculated, representing a large antigenic load requiring virtually complete functional blockade, variability of individual immune responses, restricted access of antibodies into the seminiferous tubules and epididymis and the risks of autoimmune orchitis or immune-complex disease. Passive immunization may overcome the present limited predictability of active immunization with sperm antigens to reach quickly and maintain, as well as allowing for volitionally controllable offset, of effective immunocontraceptive titers (154). The smaller antigenic burden in the female reproductive tract requiring complete neutralization suggests that a sperm vaccine, using modern genetic engineering of sperm epitopes (155), may be better targeted for administration to women. However, the most suitable targets for contraceptive vaccines might be feral and wild animals (156, 157).

CHEMICAL (NON-HORMONAL) METHODS

The lack of commercial product development for hormonal male contraceptives has made attractive the alternative option of innovative non-hormonal mechanisms to inhibit sperm production and/or function. These approaches have focused on developing feasible, druggable targets lacking off-target adverse effects for novel product development using either opportunistic or planned approaches to identify novel leads.

Opportunistic approaches include the identification through fortuitous pharmacological observation of male reproductive effects of drugs or natural products. Among older drugs, an orally active spermicide concentrated in semen (158), drugs inhibiting spermatogenesis (159), ejaculation (160) or epididymal sperm function (161) have been identified. Further, among numerous plant products and natural medicines reputed to inhibit male fertility, the most widely tested was gossypol, a polyphenolic yellow pigment identified in China as causing epidemic infertility among workers ingesting raw cottonseed oil. In over 10,000 men purified gossypol reduced sperm output to <4 million/ml in >98% within 75 days with suppression maintained by a lower weekly maintenance dose (162). Although an effective male contraceptive, the systemic toxicity of gossypol, due to mitochondrial apoptosis (163), and irreversibility of sperm suppression precluded further clinical development (164) although it has potential anti-cancer applications (163). Subsequently, extracts of Tripterygium wilfordii, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine for rheumatoid arthritis and skin disorders, decrease sperm output and function and inhibit fertility in rodents and men. Studies aiming to characterize triptolide, an active alkaloid as a potential lead for an orally effective sperm function inhibitor, reveal prominent induction of germ cell apoptosis (165) at testicular (166) in addition to a post-testicular site of action (167). Additional opportunistic approaches include recognizing that the rapidly proliferating germinal epithelium is highly susceptible to cytotoxins such as drugs, heat, or ionizing irradiation which damage germ cell replication, resulting in inhibition of spermatogenesis. However, complete elimination of sperm by non-specific toxicity compromises full reversibility and the accompanying mutagenic risk from direct interference with DNA replication precludes safe use for reversible male contraception.

Alternatively, potential non-hormonal approaches to developing chemical male contraception focus on sperm development maturation and function (168) ensuring that targets are specific for sperm (169). Such approaches may exploit the numerous biological processes required for developing functionally mature, fertile sperm that create abundant targets for reversible inhibition of male fertility (170) . Prominent targets include either reducing sperm output via non-hormonal mechanisms regulating spermatogenesis or post-testicular inhibition of sperm functions. One approach to reduce sperm output is by exploiting the essential requirement for retinoic acid in spermatogenesis (171). Experimental genetic or pharmacological inhibition of vitamin A action inhibits the generation of mature sperm and male fertility (172, 173); however, the ubiquitous roles of vitamin A in cellular replication and differentiation requires thorough safety evaluation for off-target effects in clinical trials. More specific focus on the retinoic acid alpha receptor by developing alpha-specific inhibitors continue in pre-clinical development (174). Another series of orally active indazole carboxylic acid analogs, adjudin, gamendazole and indenopyridine derivatives (175-178), have been developed from the compound lonidamine but aiming to eliminating its non-specific muscle and liver toxicity while retaining its mechanism of action in causing reversible male infertility. The indazole carboxylic acid analogs cause reversible subfertility by disrupting highly specialized intercellular junctions between elongating spermatids and Sertoli cells leading to precocious detachment of immature, elongating spermatids that are then shed prematurely from the germinal epithelium. Clinical evaluation of such drugs remains at an early pre-clinical stage. Other discoveries of molecules with specific expression in sperm and contributions to sperm development and/or fertilizing ability may provide clues to novel leads for chemical non-hormonal male contraceptive drug development. These include protein phosphatase complex (179), cyclin dependent kinase 2 (180), testis-specific bromodomain (181), homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 4 (182) and histone demethylase KDM5B (183).

The seclusion of functionally immature post-meiotic, haploid sperm during their transit through seminiferous tubules and epididymis offers targets for chemical methods to regulate male fertility as sperm are stored and mature functionally. Post-testicular targets offer the advantages of fast onset and offset of action compared with hormonal methods; however, specific target identification, selective drug targeting to the epididymis or testis and human dose optimization remain challenging problems. A model, rapid-onset oral spermicide was first provided by the chlorosugars that showed rapid, irreversible effect on rodent epididymal sperm (184) but proved too toxic for clinical development. A recent promising drug lead was the recognition that an alkylated iminosugar drugs that inhibit glucosyltransferase, used therapeutically to reduce lysosomal glycosphingolipid accumulation in storage disorder type 1 (Gaucher's disease), miglustat, was a potent and reversible oral inhibitor of male mouse fertility but free from apparent systemic toxicity (161, 185). Miglustat treatment produced structural malformation of sperm acrosome, head and mid-piece with consequential impaired motility although sperm retain the ability to fertilize oocytes in-vitro and produce normal offspring. However, miglustat effects were species- and mouse strain-dependent and were not effective in rabbits (186) or men (187). Numerous proteins identified as specifically or uniquely expressed in the epididymis provide additional opportunities for development of novel non-hormonal male contraceptive targets (188-192). Signaling enzymes involved in the epididymal acquisition of sperm motility and capacity for hyperactivation and fertilization such as sperm-specific protein phosphatase PPIγ2, glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), and calcium regulated phosphatase calcineurin (PP2B) and protein kinase A (PKA) have key role in sperm maturation, activation and fertilization that might provide clues to novel chemical, non-hormonal male contraceptive drugs (193). Post-testicular inhibition of purinergic and adrenergic receptors in the vas deferens to inhibit sperm movement through the ejaculatory ducts are feasible (194, 195), and a series of these receptor antagonists have been developed (196). However, interference with ejaculation is unlikely to be an acceptable form of male contraception. An opportunistic approach based on a FDA-approved excipient, N,N dimethylacetamide that produced a reversible reduction in fertility of rats without hormonal effects has been reported (197).

The most rapidly growing area of opportunity arises from serendipitous discoveries of genes found to be necessary for normal fertility, often from gene knock-out mouse models displaying unexpected male sterility or subfertility (170). This rapidly expanding list includes distinctive steps in spermatogenesis involving either biological processes unique to spermatogenesis, notably meiosis (two-stage reductive division of diploid germinal cells into haploid gametes) and spermiogenesis (metamorphosis of haploid round spermatids into spermatozoa) or inhibiting functions essential to sperm fertilizing ability such as flagellar motility and sperm motion (including hyperactivation (198)), excurrent ductular transport, acrosome reaction (199), chemoattraction to and fertilization of oocytes (194, 200), acrosomal function (201)and testis-specific serine/threonine kinases involved in development of normal sperm morphology and function (202, 203). The most frequent mechanisms involves inhibition of ion channels in sperm (200, 204-211) or vas deferens smooth muscle (194, 195) leading to inhibition of sperm motility, hyperactivation and/or transport required for fertilization. One leading candidate is CatSper, the principal calcium channel activated by progesterone (212-216) and essential for the sperm hyperactivation required for fertilization (217). Experimental vaccines against CatSper epitopes inhibit murine fertility (218, 219).

In addition, drug screening programs using extensive high-throughput chemical libraries can be employed to identify suitable lead compounds using selective sperm function targets for further development including target optimization (220). For example, the inhibitor analogs of CatSper using patch clamping to identify channel blockade have identified probes suitable for drug discovery development (221). Similarly, screening of a chemical library identified phosducin-like 2, a testis specific phosphoprotein, which when knocked-out in mice, induced sterility due to globozoospermia with impaired sperm head formation (222) as well as screening of natural plant (223-225) and microbial (226) products continue as a source for lead compounds continues. Other products of drug screening that may interfere with DNA replication by targeting meiosis, incur additional theoretical safety risks of mutagenesis if intended for male contraception (227).

HORMONAL METHODS

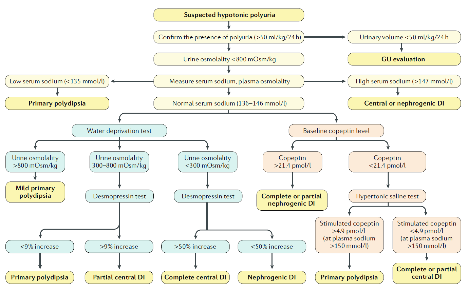

Hormonal methods are the closest to meeting the requirement for a reliable, reversible, safe, and acceptable male contraceptive. Although reliability is judged by the efficacy in preventing pregnancy in fertile female partners, as a hormonal male contraceptive aims to prevent pregnancy by reversible inhibition of sperm output, the suppression of spermatogenesis constitutes a useful surrogate marker for development and evaluation of prototype male contraceptive regimens. This makes defining the degree of suppression of sperm output required a key strategic issue in developing a hormonal male contraceptive (228).

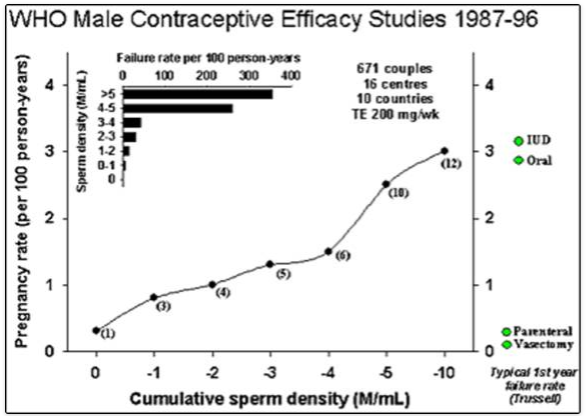

Two landmark WHO studies, the first ever male contraceptive efficacy studies, involving 671 men from 16 centers in 10 countries established the proof of principle that hormonally-induced azoospermia provides highly reliable, reversible contraception (14, 15). Among the minority (~25%) of men who remained severe oligozoospermic (0.1-3 million sperm/ml) using weekly testosterone enanthate injections, contraceptive failure rate (~8% per annum) was directly proportional to their sperm output. Hence to achieve highly effective contraception, azoospermia is analogous to anovulation as a sufficient, but not necessary, requirement. Nevertheless, reliable contraception by modern standards (29) requires uniform azoospermia as the desirable target for male contraceptive regimens (229). No regimen yet achieves this consistently in all men, although in some Asian countries (e.g. China (15), Indonesia (230, 231)) an approximation to uniform azoospermia can be achieved by a variety of regimens. A study involving 308 Chinese men in 6 centers has shown that monthly injections of testosterone undecanoate provides highly effective and reversible contraception (17). No pregnancies were recorded among men who were azoospermic or severely oligozoospermic (≤3 million sperm per mL) providing a 95% upper confidence limit of pregnancy (contraceptive failure) rate of 2.5% per annum. The overall failure rate based on suppression of spermatogenesis was <4%. The prototype regimen was well tolerated apart from injection site discomfort due to large oil injection volume (4 mL) and reversible androgenic effects (acne, weight gain, hemoglobin, lipids). Nevertheless, despite these promising findings, non-Chinese men require combination hormonal regimens involving a 2nd gonadotropin suppressing agent, notably progestins, together with testosterone to ensure uniformly adequate spermatogenic suppression. Proof-of-principle for this combination approach was provided by a depot androgen/progestin regimen that observed no pregnancies among 55 couples during 35.5 person-years of exposure (95% upper limit of failure rate ~8%) in a study with satisfactory tolerability and reversibility for a prototype regimen (18). Hence, contraceptive efficacy studies show that highly effective contraception can be achieved with suppression of sperm output to near azoospermia (≤1 million per mL) (229). Ultimately, the efficacy of male contraception must be established by enumerating pregnancies prevented, and not counting sperm. The present paucity of male contraceptive efficacy studies, for which placebo controls are ethically impossible (232), makes systematic evaluations comparing practical clinical regimens a task for the future (233).

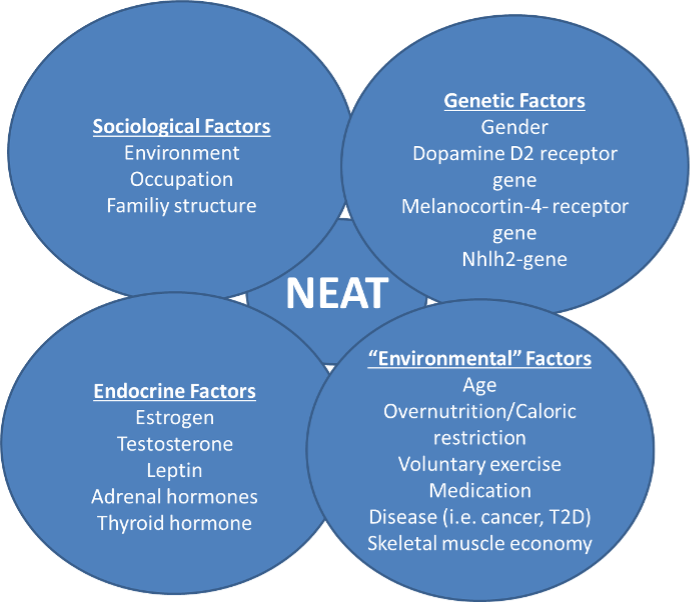

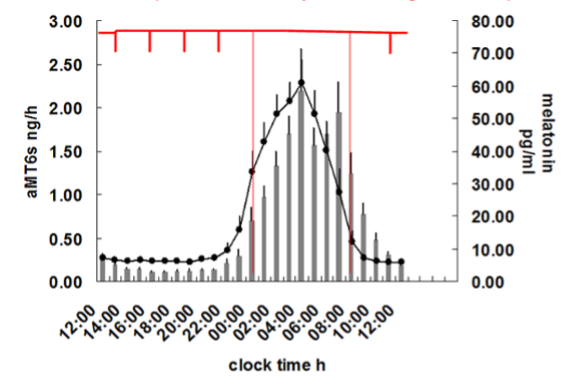

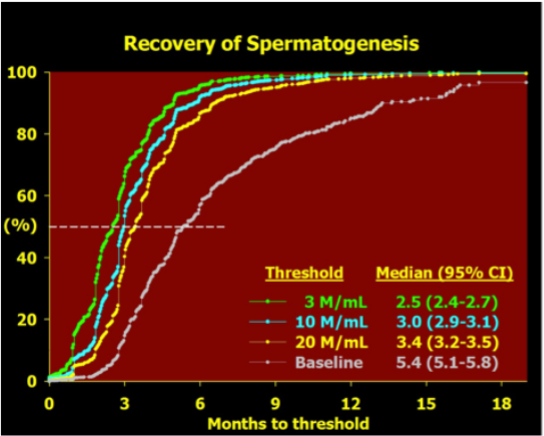

The reversibility of hormonal male contraceptive regimens is clearly established by an integrated re-analysis that pooled primary data from over 90% of all hormonal male contraceptive studies reported to show that all regimens show full reversibility within a predictable time course (234). This comprehensive review of the recovery of 1549 healthy eugonadal men, aged 18-51 years, who underwent 1283.5 man-years of treatment and 705 man-years of post-treatment recovery, showed the median times for recover to sperm densities of 10 and 20 million per mL were 2.5 months (2.4-2.7) and 3.0 months (2.9-3.1), respectively. Covariables such as age, ethnicity and hormonal or sperm output kinetics had significant but minor influence on the rate, but not the extent, of recovery.

Acceptability of a hormonal male contraceptive is high across a wide range of countries and cultures in potential male as well as female users (12). Willingness to use a hypothetical hormonal male contraceptive averaged 55% (range 29-71%) in an extensive, population representative survey of 9342 men aged 18-50 yr from 9 countries (4 Europe, 3 South America, Indonesia and USA) with consistency across a wide range of socio-economic and cultural settings (235, 236). Similar findings are reported in a 4-country study (UK, South Africa, Hong Kong, Shanghai) with 44-83% in each center (237) as well as 75% in Australia willing to try a hormonal male contraceptive (238). A majority of men in a US study were satisfied with and would recommend a transdermal gel-based hormonal contraceptive (239) and a majority of Chinese men were satisfied with monthly injections (240). Female partners from a variety of cultures also indicate high acceptability in a survey of 1894 women in 4 countries, among whom 40-78% would support and trust their male partners in stable relationships to use a hormonal male contraceptive (241). Corroborating the acceptability of hormonal male contraception are findings from experimental studies of prototype regimens for up to 12 months usage in which most participants confirm high levels of satisfaction and willingness to try a commercial product (239, 240, 242, 243).

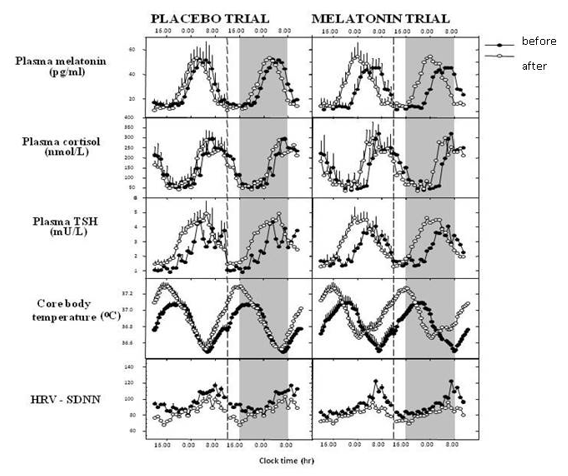

Modern safety evaluation for hormonal contraceptive methods requires long-term, large scale studies of marketed products (244). Consequently, in the absence of any marketed male contraceptive, no long-term safety profile can be discerned. Nevertheless, 4 decades of clinical trials have consistently identified mainly minor adverse effects in short- or medium-term studies of prototype male hormonal contraception regimens (1, 8, 228). This was verified in an unique, placebo-controlled study of a combined androgen-progestin regimen which again proved highly effective at reversible suppression of sperm output although the inclusion of a placebo arm rendered it ethically impossible to evaluate contraceptive efficacy but provided insight into drug-related side effects (11). The study confirmed the benign medium-term safety profile for this prototype regimen in observing few serious adverse effects, none attributable to the steroid regimen, and, among the non-serious adverse effects reported, expected androgenic effects (acne, weight gain, sweating, changes in mood or libido) were more frequent than placebo but mild and rarely led to discontinuation (11). Nevertheless, the long-term safety evaluation of novel contraceptives requires large scale observational studies of extensively used drugs to define low frequency risks but can only occur after the marketing of suitable products.

Hence, prototype hormonal methods have proven reliability and reversibility and reasonable prospects for being well accepted and safe. Although they are the most likely opportunity in the foreseeable future to develop a practical contraceptive method for men, progress depends on pharmaceutical industry development. However, leadership in male contraceptive development has come almost exclusively from university-based investigators working with public sector organizations (8), notably WHO (245), CONRAD (246), and the Population Council (247). By contrast, commitment from pharmaceutical companies, including those that flourished in the post-war decades through developing female hormonal contraception, continued to languish over recent decades (24, 248) and is effectively ceased (249).

Steroidal Methods

ANDROGEN ALONE

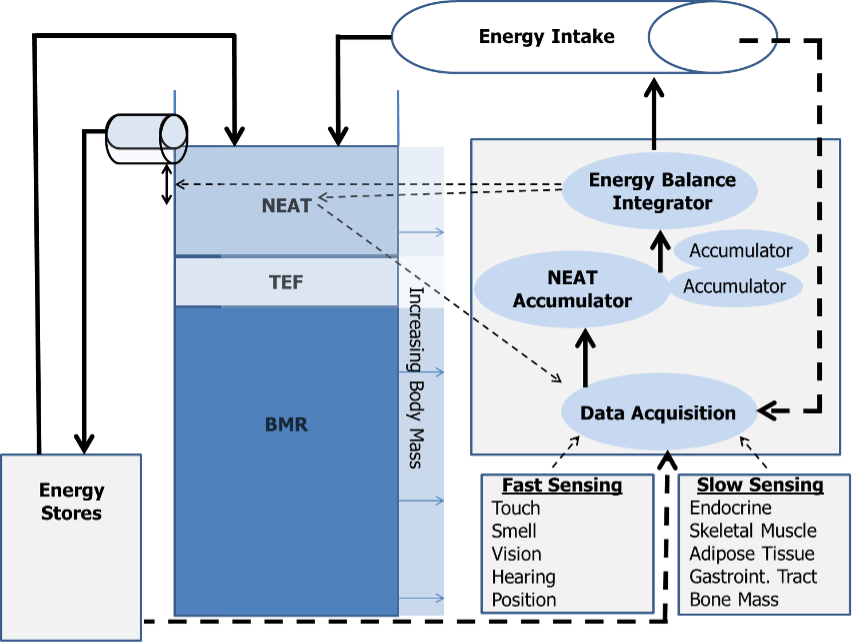

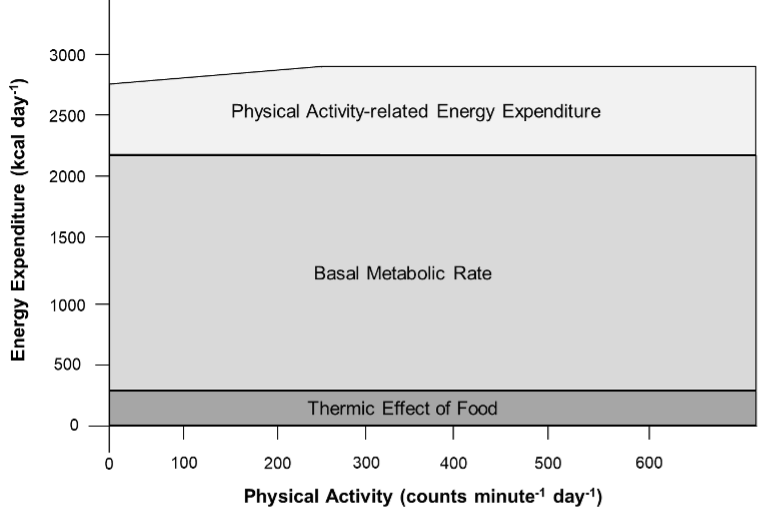

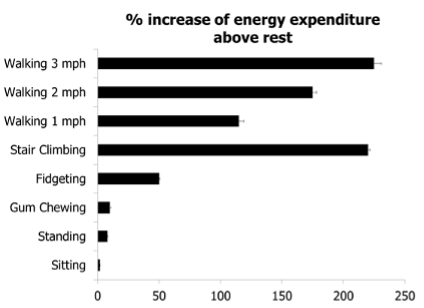

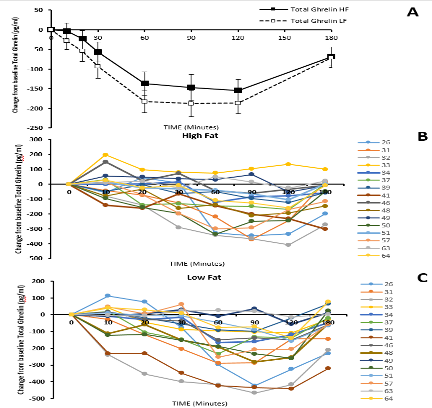

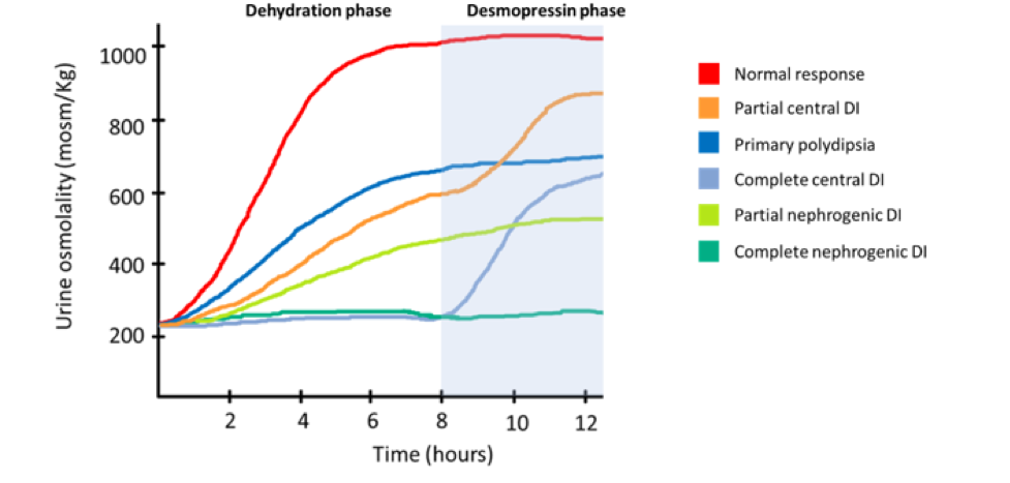

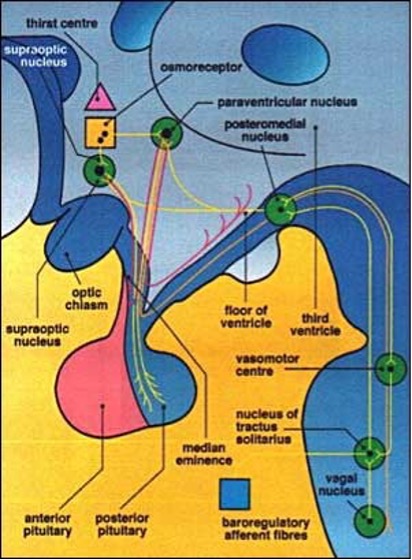

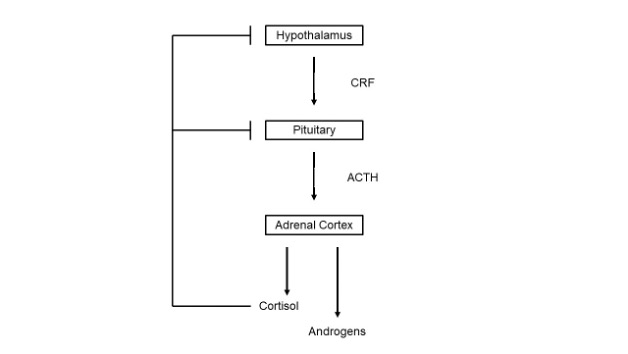

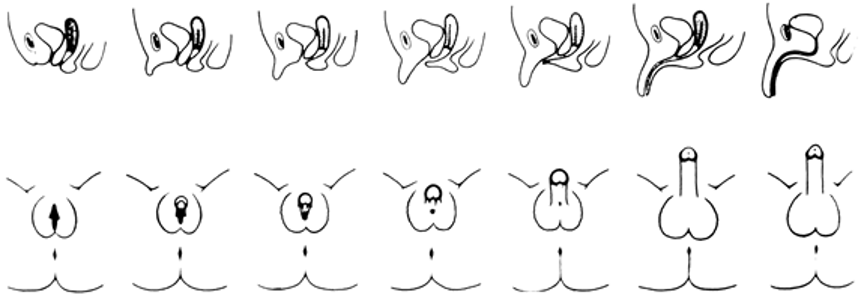

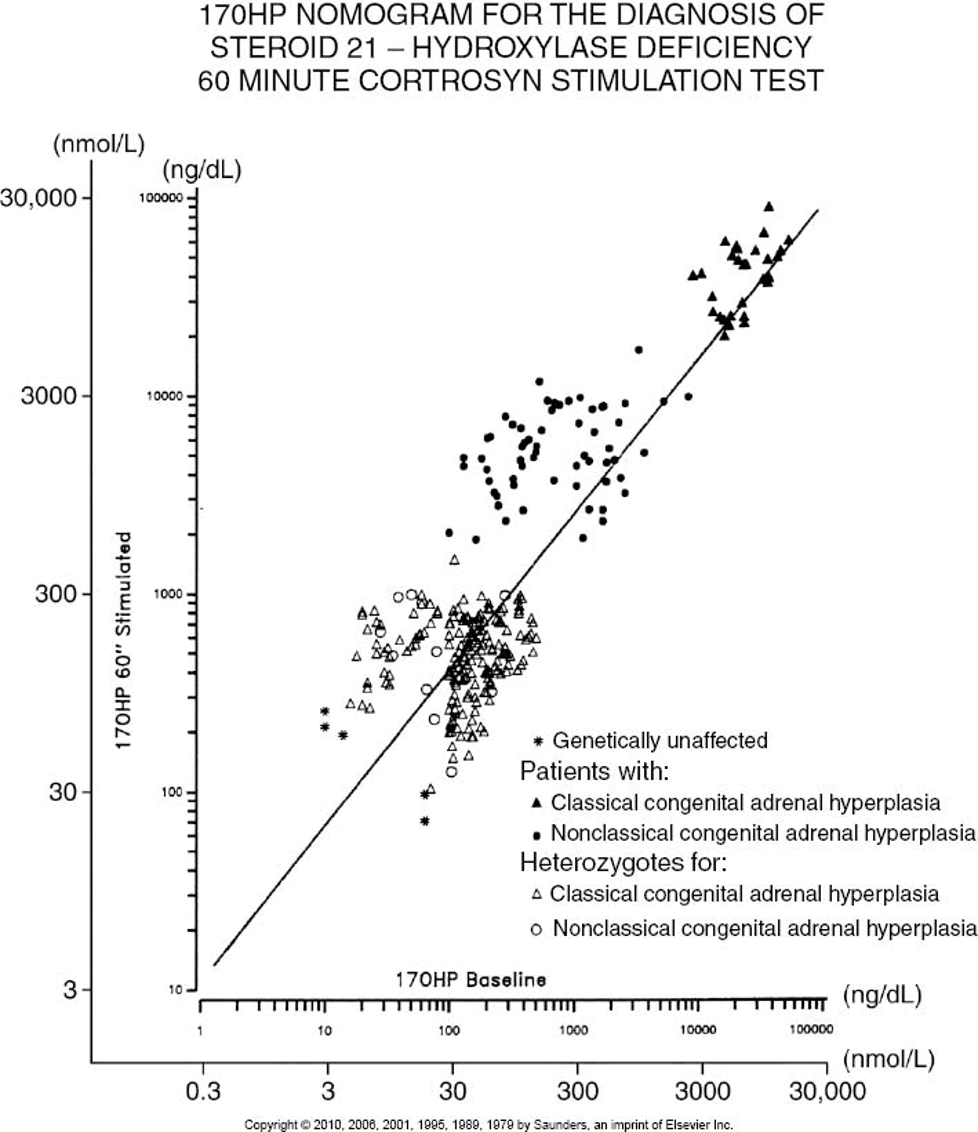

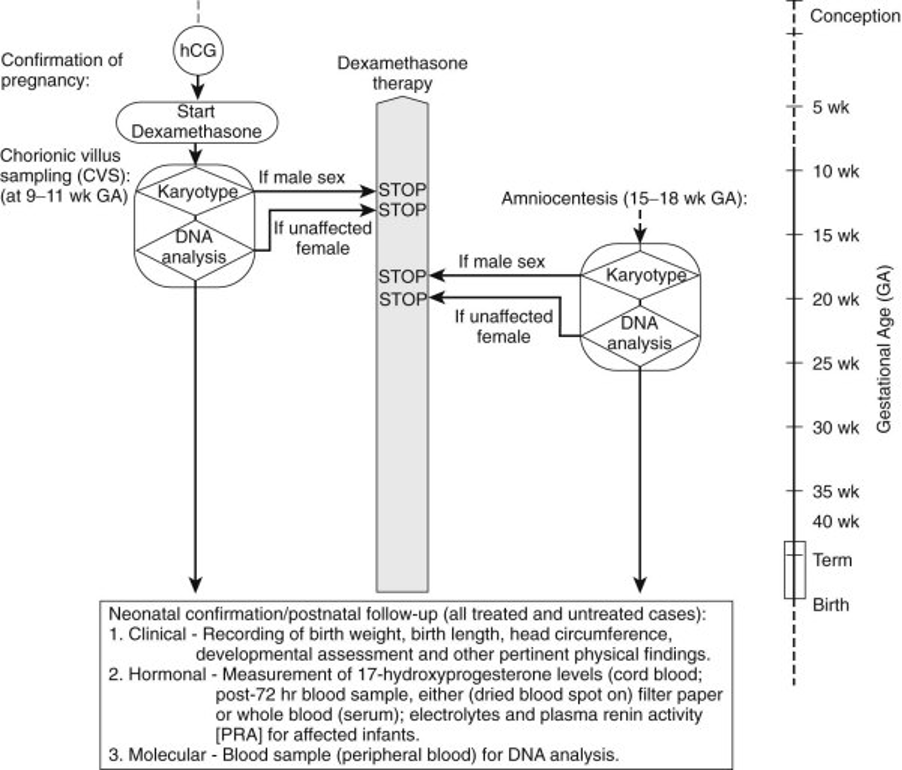

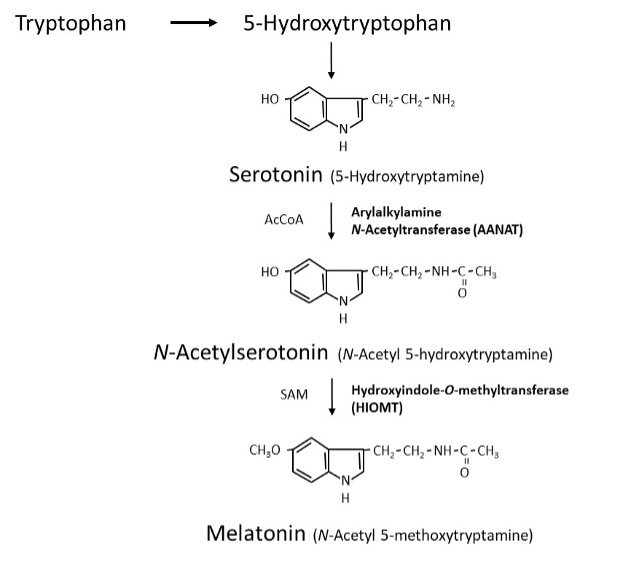

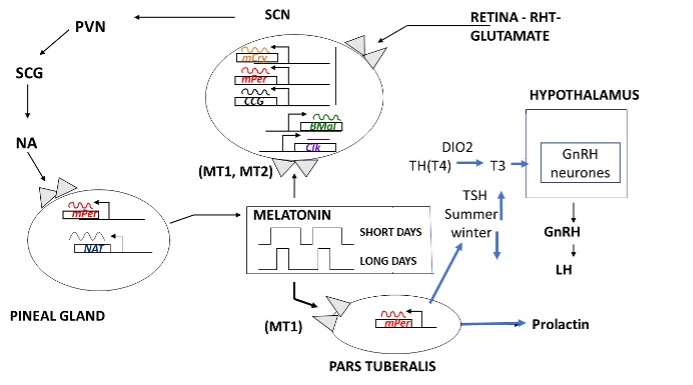

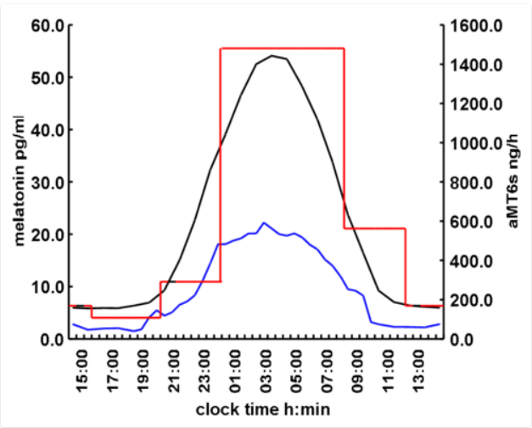

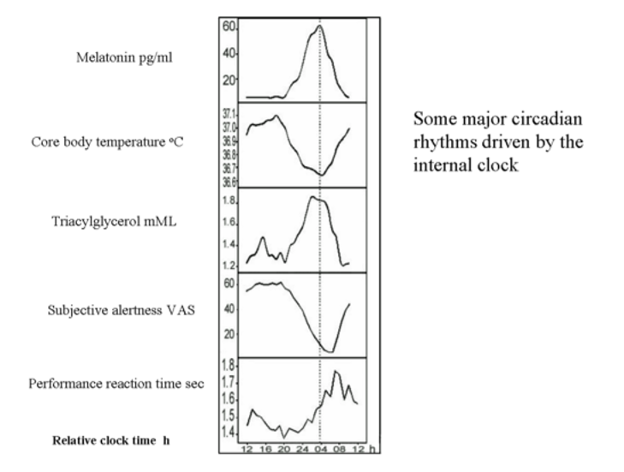

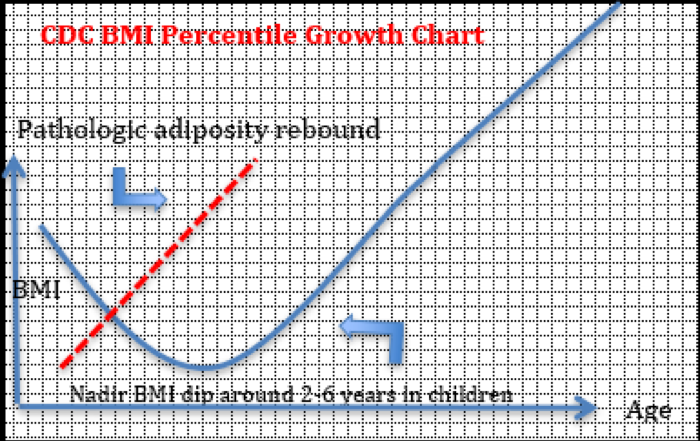

Testosterone provides both gonadotropin suppression and androgen replacement making it an obvious first choice as a single agent for a reversible hormonal male contraceptive. Although androgen-induced, reversible suppression of human spermatogenesis has long been known (250-253), systematic studies of androgens for male contraception began in the 1970's (254, 255). Feasibility and dose-finding studies (256), mostly using testosterone enanthate (TE) in an oil vehicle as a prototype, showed that weekly im injections of 100-200 mg TE induce azoospermia in most Caucasian men (257)but less frequent or lower doses fail to sustain suppression (258-261). The largest experience with an androgen alone regimen arises from the two WHO studies in which over 670 men from 16 centers in 10 countries received weekly injections of 200 mg TE. In these studies ~60% of non-Chinese and >90% of Chinese men became azoospermic and the remainder were severely oligozoospermic (14, 15) (Figure 1). The high efficacy among Chinese men has also been replicated using monthly TU injections (16, 17). Effective gonadotropin suppression is a prerequisite for effective testosterone-induced spermatogenic suppression in human (18, 262-266) and non-human primates (267, 268). However, the reasons for within and between population differences in susceptibility to hormonally-induced azoospermia remain largely unexplained (269). Possible factors include population differences in reproductive physiology of environmental (270, 271), genetic (272-274) or uncertain (275, 276) origin that may lead to differences in rate and extent of suppression of circulating gonadotropins and/or depletion of intratesticular androgens. Limited invasive studies measuring intratesticular testosterone (and DHT) suggest that the degree of depletion may not predict reliably complete suppression of sperm output (277-279) but other more widely applicable, non-invasive markers of endogenous Leydig cell function such as circulating epitestosterone (262) or 17-hydroxyprogesterone (280) or non-steroidal testicular products such as INSL3 (281) may be more analytically informative as to the relative roles of gonadotropin suppression and intratesticular androgen depletion. Exogenous testosterone causes suppression of sperm output with an average of 13 weeks to reach severe oligozoospermia (<1 million per mL) or azoospermia with suppression being maintained consistently during ongoing treatment (282) (Figure 2). Following cessation of treatment, sperm reappear within 3 months to reach sperm densities of 10 and 20 million per mL at an average of 11.5 and 13.6 weeks, respectively (282)with ultimately full recovery (10) (Figure 3). Apart from intolerance of weekly injections, there were few discontinuations due to acne, weight gain, polycythemia, or behavioral effects and these were reversible as were changes in hemoglobin, testis size, and plasma urea. There was no evidence of liver, prostate, or cardiovascular disorders (14, 15, 283).

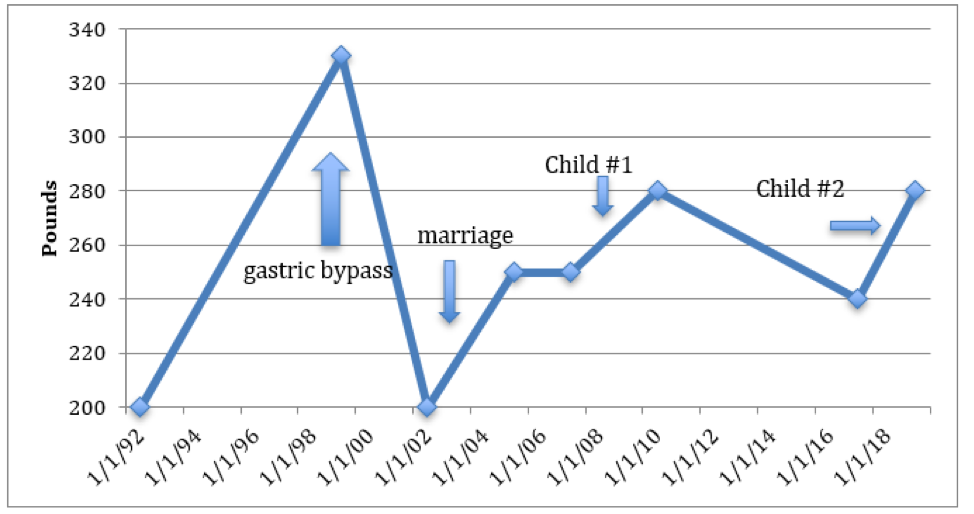

Figure 1. Pooled summary of contraceptive efficacy from two WHO male contraceptive efficacy studies (14, 15) where contraceptive failure rate (pregnancy rate) is plotted against the current sperm concentration in the ejaculate. This illustrates a summation of all data pooled from both studies. Data comprise monthly observations of the mean sperm concentration (averaging monthly sperm counts) and whether a pregnancy occurred in that month or not. Pregnancy rate (per 100 person-years, Pearl index) on the y-axis is plotted against the cumulative sperm density (in million sperm per ml) indicating that contraceptive failure rates are proportional to sperm output. The inset is the same data re-plotted in discrete sperm concentration bands rather than cumulatively. For comparison, the average contraceptive failure rates in the first year of use (33, 407) of modern reliable contraceptive methods are indicated by diamond symbols.

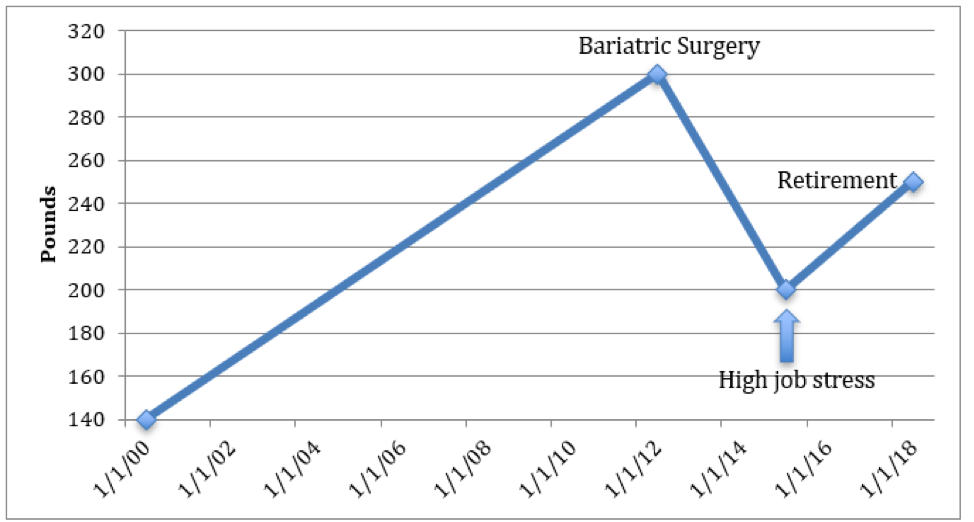

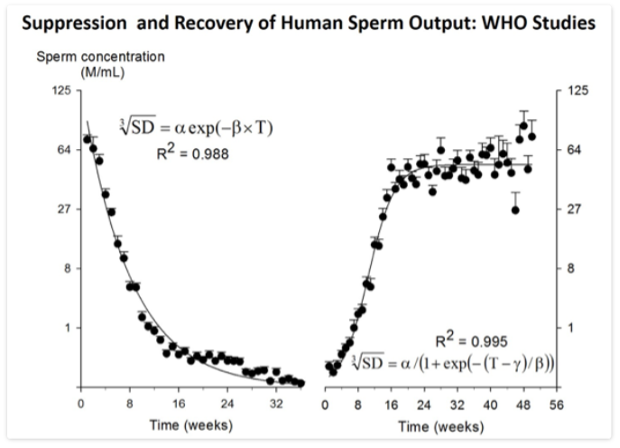

Figure 2. Plot of suppression (left panel) and recovery (right panel) of sperm output from the WHO Studies 85921 (15) and 89903 (14) involved pooling ~14,000 semen samples from 16 centers in 10 countries (282). Data-points represent mean and SE (error bar) of semen samples grouped within weeks with between six and 383 samples per time-point. Note cube-root scale on y-axis. For suppression, the smooth line is the two-parameter, single term exponential decay function plotted to fit the data by non-linear regression. For recovery, the smooth line is the three-parameter sigmoidal curve plotted to fit the data by non-linear regression.

Figure 3. Recovery of spermatogenesis after cessation of treatment with hormonal male contraceptive regimens modified after an integrated re-analysis of over 90% of all reported studies (234). Data is plotted as a Kaplan-Meier survival plot of the increasing proportion of men recovering to various thresholds over time since last treatment. The data of last treatment is defined as the time elapsed from the end of the last treatment cycle, that is the latest date of the first missed treatment dose. The thresholds are a sperm concentration of 3, 10 or 20 million sperm per mL in the ejaculate or a return to their own pre-treatment baseline sperm concentration. The median time to achieving each threshold is tabulated together with its 95% confidence interval.

The pharmacokinetics of testosterone products are crucial for suppressing sperm output. Oral androgens have major first-pass hepatic effects producing prominent route-dependent effects on hepatic protein secretion (e.g., SHBG, HDL cholesterol) and inconsistent bioavailability. Short-acting testosterone products requiring daily or more frequent administration (oral, transdermal patches or gels) which may be acceptable for androgen replacement therapy present serious feasibility challenges in compliance for effective long-term hormonal contraception. Weekly TE injections required for maximal suppression of spermatogenesis (256) are far from ideal (284) and cause supraphysiological blood testosterone levels risking both excessive androgenic side effects and preventing maximal depletion of intratesticular testosterone for optimal efficacy (285, 286). Other currently available oil-based testosterone esters (cypionate, cyclohexane-carboxylate, propionate) do not differ from the enanthate ester (287), but longer-acting depot preparations such as injectable testosterone undecanoate are a substantial improvement. Subdermal testosterone pellets sustain physiological testosterone levels for 4-6 months (288) and the newer injectable preparations testosterone undecanoate (17), testosterone-loaded biodegradable microspheres (289) and testosterone buciclate (290) provide 2-3 months duration of action. Depot androgens suppress spermatogenesis faster, at lower doses and with fewer metabolic side effects than TE injections but azoospermia is still not achieved uniformly (291) although when combined with a depot progestin, this goal is achievable (18).

Oral synthetic 17-a alkylated androgens such as methyltestosterone (292), fluoxymesterone (293), methandienone (294)and danazol (295, 296) suppress spermatogenesis but azoospermia is rarely achieved and the inherent hepatotoxicity of the 17-a alkyl substitutent (297, 298) renders them unsuitable for long-term use. Athletes self-administering supratherapeutic doses of androgens also exhibit suppression of spermatogenesis (294, 299). Synthetic androgens lacking the 17-a alkyl substituent have been little studied although injectable nandrolone esters produce azoospermia in 88% of European men (300, 301) whereas oral mesterolone is ineffective (302). On the other hand, nandrolone hexyloxyphenylpropionate alone was unable to maintain spermatogenic suppression induced by a GnRH antagonist (303) in a prototype hybrid regime (where induction and maintenance treatment differ) whereas testosterone appears more promising (304). A 7-methyl derivative of nandrolone (MeNT), which is partly aromatisable but resistant to 5α-reductive amplification of androgenic potency, has been studied as a non-oral androgen for hormonal male contraceptive regimens (305). While its non-amplification by 5α reduction may be theoretically prostate-sparing (306), dose titration to achieve essential androgen replacement at each relevant tissue might be more difficult to achieve than for testosterone (307) or impossible. Non-aromatisable androgens which lack estrogen- receptor-mediated effects such as on bone density maintenance (308) and sexual function (309, 310) may not be ideal for long-term hormonal contraception. More potent, synthetic androgens lacking 17-a alkyl groups (311, 312) remain to be evaluated.

Adverse effects due to testosterone administration in prototype hormonal contraceptive regimens include (asymptomatic) polycythemia, weight (muscle) gain, and acne as well as changes in mood or sexual behavior. These are usually minor in severity, reversible upon cessation of treatment and of minimal clinical significance (11).

The safety of androgen administration concerns mainly potential effects on cardiovascular and prostatic disease As the explanation for the higher male susceptibility to cardiovascular disease is not well understood, the risks of exogenous androgens are not clear (313, 314). In clinical trials, lipid changes are minimal with depot (non-oral) hormonal regimens (18, 291, 315, 316). Changes in blood cholesterol fractions observed during high hepatic exposure to testosterone and/or progestins, due to either oral first pass effects or high parenteral doses, have unknown clinical significance but, in any case, maintenance of physiological blood testosterone concentrations is the prudent and preferred objective. The real cardiovascular risks or benefits of hormonal male contraception will require long-term surveillance of cardiovascular outcomes (317).

The long-term effects of exogenous androgens on the prostate also require monitoring since prostatic diseases are both age and androgen dependent. Exposure to adult testosterone levels is required for prostate development and disease (318-320). The precise relationship of androgens to prostatic disease and in particular any influence of exogenous androgens remains poorly understood. Ambient blood testosterone or DHT levels do not predict development of prostatic cancer over future decades in prospective studies of adults (321). A genetic polymorphism, the CAG (polyglutamine) triplet repeat in exon 1 of the androgen receptor, is an important determinant of prostate sensitivity to circulating testosterone with short repeat lengths leading to increased androgen sensitivity (322), however the relationship of the CAG triplet repeat length polymorphism to late-life prostate diseases remains unclear (323). Among androgen deficient men, prostate size and PSA concentrations are reduced and returned towards normal by testosterone replacement without exceeding age-matched eugonadal controls (322, 324-326). In healthy middle-aged men without known prostate disease, very high doses of the potent natural androgen DHT for 2 years did not increase prostate size or age-related growth rate compared with placebo indicating that effects of even high dose exogenous androgen treatment has much less effect than age on the human prostate (308). Similarly, self-administration of massive androgen over-dosage does not increase total prostate volume or PSA in anabolic steroid abusers although central prostate zone volumes increases (327). In-situ prostate cancer is common in all populations of older men whereas rates of invasive prostate cancer differ many-fold between populations despite similar blood testosterone concentrations. This suggests that early and prolonged exposure to androgens may initiate in-situ prostate cancer, but later androgen-independent environmental factors promote the outbreak of invasive prostate cancer. Therefore, it is prudent to maintain physiological androgen levels with exogenous testosterone, which then might be no more hazardous than exposure to endogenous testosterone. Prolonged surveillance comparable with that for cardiovascular and breast disease in users of female hormonal contraception would be equally essential to monitor both cardiovascular and prostatic disease risk in men receiving exogenous androgens for hormonal contraception.

Extensive experience with testosterone in doses equivalent to replacement therapy in normal men indicates minimal effects on mood or behavior (14, 15, 256, 328-330). A careful placebo-controlled, cross-over study showed that a 1000 mg TU injection in healthy young men produces minor mood changes without any detectable increase in self or partner-reported aggressive, non-aggressive or sexual behaviors (331). By contrast, extreme androgen doses used experimentally in healthy men can produce idiosyncratic hypomanic reactions in a minority (332). Aberrant behavior in observational studies of androgen-abusing athletes or prisoners are difficult to interpret particularly to distinguished genuine androgen effects from the influence of self-selection for underlying psychological morbidity (333).

ANTI-ANDROGENS

Antiandrogens have been used to selectively inhibit epididymal and testicular effects of testosterone without impeding systemic androgenic effects (334). Cyproterone acetate, a steroidal antiandrogen with progestational activity, suppresses gonadotropin secretion without achieving azoospermia but leads to androgen deficiency when used alone (335). In contrast, pure non-steroidal antiandrogens lacking androgenic or gestagenic effects such as flutamide, nilutamide and casodex fail to suppress spermatogenesis when used alone (336, 337). Two studies evaluating the hypothesis that incomplete suppression of spermatogenesis is due to persistence of testicular DHT have reported no additional suppression from administration of finasteride, a type II 5a reductase inhibitor (338, 339); however as testes express predominantly the type I isoforms (340), further studies are required to conclusively test this hypothesis using an inhibitor of type I 5-a reductase (341).

ANDROGEN COMBINATION REGIMENS

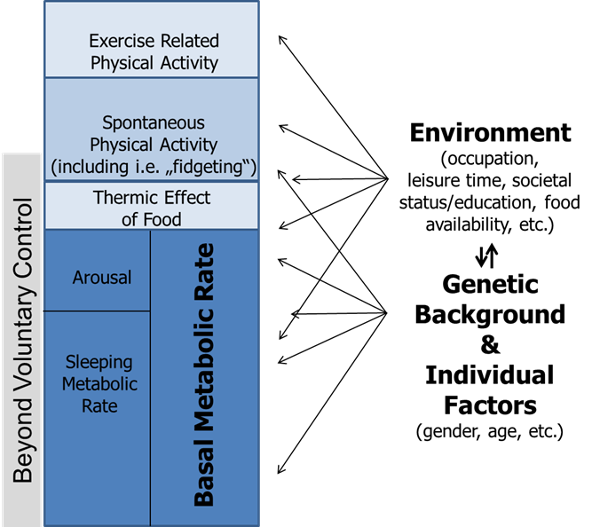

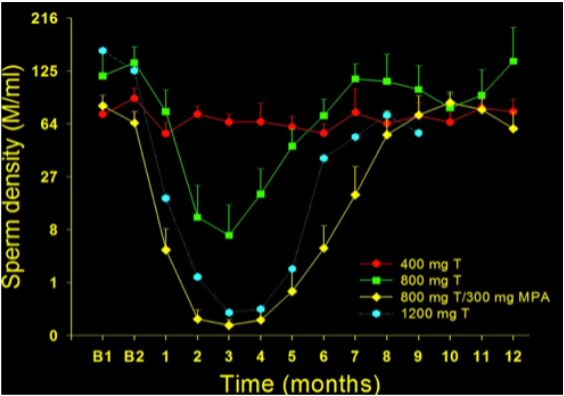

Combination steroid regimens use non-androgenic steroids (estrogens, progestins) to suppress gonadotropins, in conjunction with testosterone for androgen replacement, have shown the most promising efficacy with enhanced rate and extent of spermatogenic suppression compared with androgen alone regimens (315, 342, 343). Synergistic combinations reduce the effective dose of each steroid and minimizing testosterone dosage could enhance spermatogenic suppression if high blood testosterone levels counteract the necessary maximal depletion of intratesticular testosterone (344, 345) as well as reducing androgenic side-effects (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Plot of time course of sperm output (expressed as sperm density in millions of sperm per mL) before and after implantation of two 200-mg testosterone pellets (400 mg total; closed circles), four 200-mg testosterone pellets (800 mg total; closed squares), four testosterone pellets plus depot progestin (800 mg total testosterone plus 300 mg DMPA; closed diamonds) and six 200 mg testosterone pellets mg (1200 mg total; open hexagons) in healthy fertile men (262). Results expressed as the mean and SEM. Note the cube root transformed scale on the y-axis.

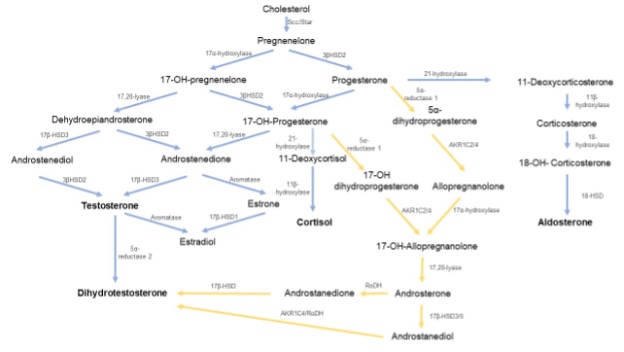

Progesterone is a key precursor and steroidogenic intermediate for all bioactive natural steroids and the progesterone receptors A and B are structurally and evolutionarily the closest members of the nuclear receptor superfamily to the androgen receptor. Yet, although progesterone has crucial gestational and lactational roles in female reproductive physiology, it has no well-established role in male reproductive physiology apart from a possible role in sperm function (200, 346), possibly via non-genomic rather than a classically genomic mechanism (347). Nevertheless functional nuclear progesterone receptors are expressed in male brain, smooth muscle and reproductive, but not most non-reproductive, tissues (348). Synthetic progestins, steroidal structural agonistic analogs of progesterone, are potent inhibitors of pituitary gonadotropin secretion used widely for female contraception and hormonal treatment of disorders such as endometriosis, uterine myoma and mastalgia. Used alone, progestins suppress spermatogenesis but cause androgen deficiency including impotence (349, 350) so androgen replacement is necessary. Non-human primate studies indicate that this is mediated via a central hypothalamic-pituitary site of action rather than direct effects on the testis (351). Extensive feasibility studies concluded that progestin-androgen combination regimens had promise as hormonal male contraceptives if more potent and durable agents were developed (256, 352). The largest and most detailed multi-center study of the contraceptive efficacy of a androgen-progestin combination involving 320 healthy men aged 18-45 years together with their 18-38 year old female partners, both without known fertility problems, studied for up to 56 weeks while having intramuscular injections of 200 mg norethisterone acetate and testosterone undecanoate every 8 weeks that produced near-complete suppression (96% declined to <1 million/ml by 24 weeks) and reversible recovery (95% recovered by 52 weeks) of sperm output (353). Four pregnancies occurred in partners of 266 men with a pregnancy failure rate of 1.6% (95% confidence interval 0.6-4.1%). Prior information on androgen/progestin regimens derives from studies with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) combined with testosterone. Monthly injections of both agents or daily oral progestin with dermal androgen gels produce azoospermia in ~60% of fertile men of European background with the remainder having severe oligozoospermia and impaired sperm function (256, 352, 354). Nearly uniform azoospermia is produced in men treated with depot MPA and either of two injectable androgens in Indonesian men (230, 231) or testosterone depot implants in Caucasian men (315). Smaller studies with other oral progestins such as levonorgestrel (342, 355, 356) and norethisterone (357, 358) combined with testosterone demonstrate similar efficacy to oral MPA whereas cyproterone acetate with its additional anti-androgenic activity has higher efficacy in conjunction with TE (343, 359) but not oral testosterone undecanoate (360). Highly effective suppression of spermatogenesis is reported with depot progestins in the form of non-biodegradable implants of norgestrel (361-363) or etonorgestrel (364, 365) or depot injectable medroxyprogesterone acetate (18, 315, 366, 367) or norethisterone enanthate (368, 369)coupled with testosterone (370). A comparative study showed that all four progestins (cyproterone acetate, levonorgestrel, norethisterone acetate and nesterone) displayed significant short-term gonadotrophin suppression when combined with testosterone (371). The pharmacokinetics of the testosterone preparation is critical to efficacy of spermatogenic suppression with long-acting depots being most effective while transdermal delivery is less effective than injectable testosterone (361). Progestin side-effects are few if sexual function and well-being are maintained by adequate doses of testosterone replacement. The metabolic effects depend on specific regimen with oral administration and higher testosterone doses exhibiting more prominent hepatic effects such as lowering SHBG and HDL cholesterol. After treatment ceases with depletion or withdrawal of hormonal depots, spermatogenesis recovers completely but gradually consistent with the time-course of the spermatogenic cycle (234, 282). Steroids with dual androgen and progestin properties may be potentially well suited to male contraception if the balance between these two bioactivities is properly balanced (372). A study comparing a gel combining nesterone (8.3 mg) with testosterone (62.5 mg) with the same dose of testosterone alone for daily transdermal application for 28 days demonstrated suppression of sperm output and serum gonadotropin to levels consistent with contraceptive efficacy and superior to testosterone alone indicating the suitability of the combination gel for further product development (373). Two orally active nandrolone derivatives, dimethandrolone (374-376) and 11-methyl nandrolone dodecylcarbonate (377), are undergoing promising, early stage clinical development showing high acceptability in a short-term, placebo-controlled clinical trials (378, 379). Whether such daily use oral or transdermal gel (239, 380)-based male contraceptives will have sufficient user compliance to attain high contraceptive efficacy remains to be evaluated.

Estradiol augments testosterone-induced suppression of primate spermatogenesis (381) and fertility (382) but estrogenic side-effects (gynecomastia) and modest efficacy at tolerable doses make estradiol-based combinations impractical for male contraception (383). The efficacy and tolerability of newer estrogen analogs in combination with testosterone remain to be evaluated.

GONADOTROPIN-RELEASING HORMONE BLOCKADE

The pivotal role of GnRH in the hormonal control of testicular function makes it an attractive target for biochemical regulation of male fertility. Blockade of GnRH action by GnRH receptor blockade with synthetic analogs or GnRH immunoneutralization would eliminate LH and testosterone secretion requiring testosterone replacement. Many superactive GnRH agonists are used to induce reversible medical castration for androgen-dependent prostate cancer by causing a sustained, paradoxical inhibition of gonadotropin and testosterone secretion and spermatogenesis due to pituitary GnRH receptor downregulation. When combined with testosterone, GnRH agonists suppress spermatogenesis but rarely achieve azoospermia (344, 345, 384) being less effective than androgen/progestin regimens. By contrast, pure GnRH antagonists create and sustain immediate competitive blockade of GnRH receptors (385, 386) and, in combination with testosterone, are highly effective at suppressing spermatogenesis. Early hydrophobic GnRH antagonists were difficult to formulate and irritating, causing injection site mast cell histamine release. Newer more potent but less irritating GnRH antagonists produce rapid, reversible and complete inhibition of spermatogenesis in monkeys (387-389) and men (390, 391) when combined with testosterone. The striking superiority of GnRH antagonists over agonists may be due to more effective and immediate inhibition of gonadotropin secretion and thereby more effective depletion of intratesticular testosterone. Due to their highly specific site of action, GnRH analogs have few unexpected side-effects. Depot GnRH antagonist plus testosterone formulations suitable for administration at up to 3-month intervals could be promising as a hormonal male contraceptive regimen. Whether GnRH antagonists are more cost-effective than progestins as the second, non-androgenic component of combination male hormonal contraceptive regimens remains to be established (278, 303, 367, 392). The drawback of higher cost might be overcome by hybrid regimens using GnRH antagonists to initiate suppression followed by a switch to more economical steroids for maintenance of spermatogenic suppression in humans (304). A GnRH vaccine could intercept GnRH in the pituitary-portal bloodstream preventing its reaching pituitary GnRH receptors. A limitation of a GnRH vaccine is its uncertain and/or unpredictable reversibility. If it is not irreversible, the offset of contraceptive efficacy may vary between individuals and create practical difficulties in ensuring reliable contraception. Gonadotropin-selective immunocastration would require androgen replacement in men (393) and pilot feasibility studies in advanced prostate cancer are underway (394)but the prospects for acceptably safe application for male contraception remain doubtful (395). By contrast there are growing applications for anti-hormonal contraceptive vaccines in control of companion (pet), agricultural, zoo, feral and wild animal populations (156, 396).

FOLLICLE STIMULATING HORMONE BLOCKADE

Selective FSH blockade theoretically offers the opportunity to reduce spermatogenesis without inhibiting endogenous testosterone secretion. FSH action could be abolished by selective inhibition of pituitary FSH secretion with inhibin (397)or novel steroids (398), by FSH vaccine (399, 400) or by FSH receptor blockade with peptide antagonists (401). Although FSH was considered essential to human spermatogenesis, spermatogenesis and fertility persist in rodents (402-404) and humans (405) lacking FSH bioactivity. Even complete FSH blockade alone might produce insufficient reduction in sperm output and function required for adequate contraceptive efficacy (406). In addition to the usual safety concerns of contraceptive vaccines including autoimmune hypophysitis, orchitis or immune-complex disease, an FSH vaccine might be overcome by reflex increases in pituitary FSH secretion. Hence, FSH suppression is a necessary but not sufficient for a hormonal male contraceptive regimen.

REFERENCES

1. Anderson RA, Baird DT 2002 Male contraception. Endocrine Reviews 23(6):735-762

2. United Nations 2006 Levels and trends of contraceptive use as assessed in 2002. New York: Department of International Economic and Social Affairs

3. Trussell J, Lalla AM, Doan QV, Reyes E, Pinto L, Gricar J 2009 Cost effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States. Contraception 79(1):5-14

4. Sedgh G, Singh S, Hussain R 2014 Intended and unintended pregnancies worldwide in 2012 and recent trends. Stud Fam Plann 45(3):301-314

5. Connelly M 2008 Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population. Cambridge, Mass., United States: Harvard University Press

6. Mosher S 2008 Population Control: Real Costs, Illusory Benefits. Somerset, NJ, United States: Transaction Publishers

7. Nguyen BT, Brown AL, Jones F, Jones L, Withers M, Ciesielski KM, Franks JM, Wang C 2021 "I'm not going to be a guinea pig:" Medical mistrust as a barrier to male contraception for Black American men in Los Angeles, CA. Contraception 104(4):361-366

8. Nieschlag E 2010 Clinical trials in male hormonal contraception. Contraception 82(5):457-470

9. Liu PY, Swerdloff RS, Anawalt BD, Anderson RA, Bremner WJ, Elliesen J, Gu YQ, Kersemaekers WM, McLachlan RI, Meriggiola MC, Nieschlag E, Sitruk-Ware R, Vogelsong K, Wang XH, Wu FC, Zitzmann M, Handelsman DJ, Wang C 2008 Determinants of the rate and extent of spermatogenic suppression during hormonal male contraception: an integrated analysis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 93(5):1774-1783

10. Liu PY, Swerdloff RS, Christenson PD, Handelsman DJ, Wang C 2006 Rate, extent, and modifiers of spermatogenic recovery after hormonal male contraception: an integrated analysis. Lancet 367(9520):1412-1420

11. Mommers E, Kersemaekers WM, Elliesen J, Kepers M, Apter D, Behre HM, Beynon J, Bouloux PM, Costantino A, Gerbershagen HP, Gronlund L, Heger-Mahn D, Huhtaniemi I, Koldewijn EL, Lange C, Lindenberg S, Meriggiola MC, Meuleman E, Mulders PF, Nieschlag E, Perheentupa A, Solomon A, Vaisala L, Wu FC, Zitzmann M 2008 Male hormonal contraception: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93(7):2572-2580

12. Glasier A 2010 Acceptability of contraception for men: a review. Contraception 82(5):453-456

13. Reynolds-Wright JJ, Cameron NJ, Anderson RA 2021 Will Men Use Novel Male Contraceptive Methods and Will Women Trust Them? A Systematic Review. J Sex Res 58(7):838-849

14. WHO Task Force on Methods for the Regulation of Male Fertility 1996 Contraceptive efficacy of testosterone-induced azoospermia and oligozoospermia in normal men. Fertility and Sterility 65(821-829

15. WHO Task Force on Methods for the Regulation of Male Fertility 1990 Contraceptive efficacy of testosterone-induced azoospermia in normal men. Lancet 336(955-959

16. Gu Y, Liang X, Wu W, Liu M, Song S, Cheng L, Bo L, Xiong C, Wang X, Liu X, Peng L, Yao K 2009 Multicenter contraceptive efficacy trial of injectable testosterone undecanoate in Chinese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94(6):1910-1915

17. Gu YQ, Wang XH, Xu D, Peng L, Cheng LF, Huang MK, Huang ZJ, Zhang GY 2003 A multicenter contraceptive efficacy study of injectable testosterone undecanoate in healthy Chinese men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 88(2):562-568

18. Turner L, Conway AJ, Jimenez M, Liu PY, Forbes E, McLachlan RI, Handelsman DJ 2003 Contraceptive efficacy of a depot progestin and androgen combination in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88(10):4659-4667

19. Soufir JC, Meduri G, Ziyyat A 2011 Spermatogenetic inhibition in men taking a combination of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate and percutaneous testosterone as a male contraceptive method. Hum Reprod 26(7):1708-1714

20. Dorman E, Perry B, Polis CB, Campo-Engelstein L, Shattuck D, Hamlin A, Aiken A, Trussell J, Sokal D 2018 Modeling the impact of novel male contraceptive methods on reductions in unintended pregnancies in Nigeria, South Africa, and the United States. Contraception 97(1):62-69

21. Jacobsohn T, Nguyen BT, Brown JE, Thirumalai A, Massone M, Page ST, Wang C, Kroopnick J, Blithe DL 2022 Male contraception is coming: Who do men want to prescribe their birth control? Contraception 115(44-48

22. Tcherdukian J, Mieusset R, Netter A, Lechevallier E, Bretelle F, Perrin J 2022 Knowledge, professional attitudes, and training among health professionals regarding male contraceptive methods. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 27(5):397-402

23. Nguyen BT, Jacobsohn TL 2022 Post-abortion contraception, an opportunity for male partners and male contraception. Contraception 115(69-74

24. Handelsman DJ 2003 Hormonal male contraception--lessons from the East when the Western market fails. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 88(2):559-561

25. Nickels LM, Shane K, Vahdat HL 2022 Catalyzing momentum in male contraceptive development†. Biol Reprod 106(1):1-3

26. Balbach M, Fushimi M, Huggins DJ, Steegborn C, Meinke PT, Levin LR, Buck J 2020 Optimization of lead compounds into on-demand, nonhormonal contraceptives: leveraging a public-private drug discovery institute collaboration†. Biol Reprod 103(2):176-182

27. WHO Task Force on Methods for the Determination of the Fertile Period 1983 A prospective multicentre trial of the ovulation method of natural family planning. III Characteristics of the menstrual cycle and of the fertile phase. Fertility and Sterility 40(773-778

28. Trussell J, Grummer-Strawn L 1990 Contraceptive failure of the ovulation method of periodic abstinence. Family Planning Perspectives 22(2):65-75

29. Trussell J 2011 Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 83(5):397-404

30. Moreau C, Bouyer J, Bajos N, Rodriguez G, Trussell J 2009 Frequency of discontinuation of contraceptive use: results from a French population-based cohort. Hum Reprod 24(6):1387-1392

31. Moreau C, Trussell J, Rodriguez G, Bajos N, Bouyer J 2007 Contraceptive failure rates in France: results from a population-based survey. Hum Reprod 22(9):2422-2427

32. Rogow D, Horowitz S 1995 Withdrawal: a review of the literature and an agenda for research. Studies in Family Planning 26(3):140-153

33. Kost K, Singh S, Vaughan B, Trussell J, Bankole A 2008 Estimates of contraceptive failure from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Contraception 77(1):10-21

34. Potts M, Diggory P 1983 Textbook of Contraceptive Practice. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

35. Sundaram A, Vaughan B, Kost K, Bankole A, Finer L, Singh S, Trussell J 2017 Contraceptive Failure in the United States: Estimates from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 49(1):7-16

36. Crosby R, Graham C, Milhausen R, Sanders S, Yarber W, Shrier LA 2015 Associations between rushed condom application and condom use errors and problems. Sex Transm Infect 91(4):275-277

37. Steiner MJ, Cates W, Jr., Warner L 1999 The real problem with male condoms is nonuse. Sex Transm Dis 26(8):459-462

38. Grady WR, Klepinger DH, Nelson-Wally A 1999 Contraceptive characteristics: the perceptions and priorities of men and women. Fam Plann Perspect 31(4):168-175

39. Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS, Solomon HM, Lyszkowski AD 1996 The male polyurethane condom: a review of current knowledge. Contraception 53(3):141-146

40. Gallo MF, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF 2006 Non-latex versus latex male condoms for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev1):CD003550

41. Cates W, Jr., Steiner MJ 2002 Dual protection against unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections: what is the best contraceptive approach? Sex Transm Dis 29(3):168-174

42. Carey RF, Lytle CD, Cyr WH 1999 Implications of laboratory tests of condom integrity. Sex Transm Dis 26(4):216-220

43. Walsh TL, Frezieres RG, Peacock K, Nelson AL, Clark VA, Bernstein L, Wraxall BG 2003 Use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) to measure semen exposure resulting from male condom failures: implications for contraceptive efficacy and the prevention of sexually transmitted disease. Contraception 67(2):139-150

44. Doncel GF 2006 Exploiting common targets in human fertilization and HIV infection: development of novel contraceptive microbicides. Hum Reprod Update 12(2):103-117

45. Liskin L, Benoit E, Blackburn R 1992 Vasectomy: New Opportunities. Baltimore: Population Information Program, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

46. Zhang X, Eisenberg ML 2022 Vasectomy utilization in men aged 18-45 declined between 2002 and 2017: Results from the United States National Survey for Family Growth data. Andrology 10(1):137-142

47. Drake MJ, Mills IW, Cranston D 1999 On the chequered history of vasectomy. BJU Int 84(4):475-481

48. EngenderHealth 2002 Contraceptive Sterilization: Global Trends and Issues. New York

49. Schwingl PJ, Guess HA 2000 Safety and effectiveness of vasectomy. Fertility and Sterility 73(5):923-936

50. Awsare NS, Krishnan J, Boustead GB, Hanbury DC, McNicholas TA 2005 Complications of vasectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 87(6):406-410

51. Sokal D, Irsula B, Hays M, Chen-Mok M, Barone MA 2004 Vasectomy by ligation and excision, with or without fascial interposition: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med 2(1):6

52. Cook LA, Van Vliet HA, Lopez LM, Pun A, Gallo MF 2014 Vasectomy occlusion techniques for male sterilization. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3(Cd003991

53. Li S, Goldstein M, Zhu J, Huber D 1991 The no-scalpel vasectomy. Journal of Urology 145(341-344

54. Sokal D, McMullen S, Gates D, Dominik R 1999 A comparative study of the no scalpel and standard incision approaches to vasectomy in 5 countries. The Male Sterilization Investigator Team. Journal of Urology 162(5):1621-1625

55. Cook LA, Pun A, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Van Vliet HA 2014 Scalpel versus no-scalpel incision for vasectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3(Cd004112

56. Christiansen CG, Sandlow JI 2003 Testicular pain following vasectomy: a review of postvasectomy pain syndrome. J Androl 24(3):293-298

57. Leslie TA, Illing RO, Cranston DW, Guillebaud J 2007 The incidence of chronic scrotal pain after vasectomy: a prospective audit. BJU Int 100(6):1330-1333

58. Aradhya KW, Best K, Sokal DC 2005 Recent developments in vasectomy. Bmj 330(7486):296-299

59. Cook LA, Pun A, van Vliet H, Gallo MF, Lopez LM 2007 Scalpel versus no-scalpel incision for vasectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev2):CD004112

60. Barone MA, Irsula B, Chen-Mok M, Sokal DC 2004 Effectiveness of vasectomy using cautery. BMC Urol 4(1):10