ABSTRACT

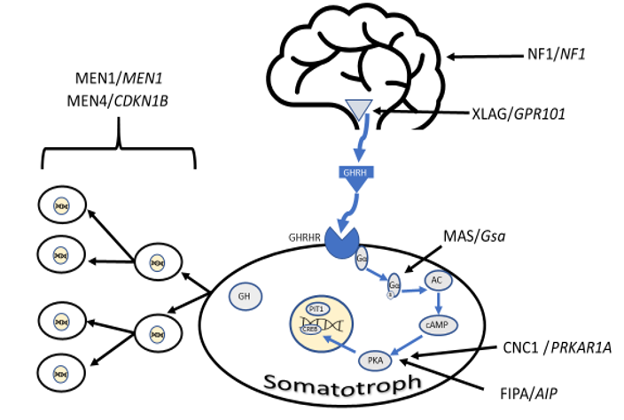

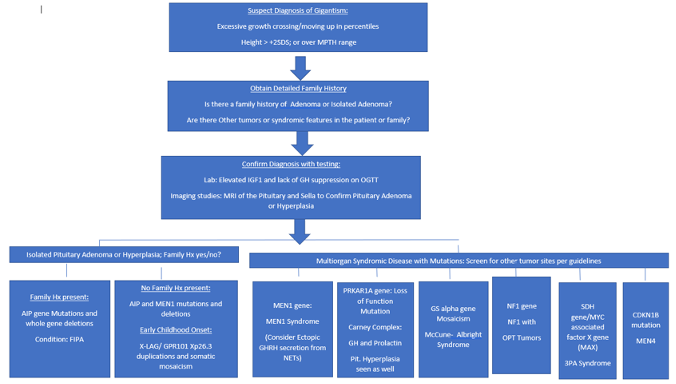

Growth is a fundamental process of childhood and growth disorders remain one of the commonest reasons for referral to a pediatric endocrinologist. Growth can be divided into four phases – fetal, infancy, childhood and the pubertal phase with different hormonal components influencing growth at each stage. The GH-IGF1 axis plays a major role in the childhood phase of growth with a significant role alongside sex steroids during puberty while in infancy thyroid hormone and nutrition are vital. Although an uncommon cause of short stature disorders of the GH-IGF1 axis are extremely important due to the effectiveness of recombinant human growth hormone therapy for the child with GH deficiency (GHD). Here we review the diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency through a combination of auxology, biochemistry, imaging, and genetic testing. Particular focus is given to the accuracy of IGF-1/BP3 for diagnosis as well as the known problems with GH stimulation tests and GH assays. Isolated GHD is caused by mutations in GH1, BTK, and RNPC3 while GHD seen as part of multiple pituitary hormone deficiency is known to be caused by mutations in a wide variety of genes. A variety of structural malformations of the brain can be associated with congenital GHD with the commonest being the presence of an ectopic posterior pituitary or Septo-optic dysplasia. Acquired GHD is rarer and caused by tumors, radiotherapy, hypophysitis, and traumatic brain injury. Treatment with recombinant human GH is highly efficacious in improving height in children with GH deficiency and extremely safe. Short stature disorders are, rarely, also caused by a variety of other disorders of the GH-IGF1 axis. Resistance to growth hormone is seen in Laron syndrome and in mutations in IGF1 and IGF1R while decreased bioavailability of IGF1 is seen in ALS deficiency and PAPPA2 deficiency. Treatment with recombinant human IGF1 (rhIGF1) is available for those with IGF-I deficiency caused by either Laron syndrome or IGF1 mutations. rhIGF1 is effective in improving height but treatment is less effective than the use of GH to treat GH deficiency. The role of IGF1 in pre-natal growth is highlighted by the phenotype of patients with IGF1R or IGF1 mutations where pre-natal growth is commonly impaired and children born small for gestational age. GH excess is much rarer than GH deficiency in childhood and can be caused by pituitary adenomas, optic nerve gliomas (seen predominantly with NF1), McCune Albright syndrome, or Carney complex. Treatment is with surgery, somatostatin analogs, or GH receptor antagonists.

CASE STUDY

A 5-year-old girl was referred to her local community pediatrician by her health visitor with concerns about growth and poor calorie intake. Height at presentation was 91.5 cm (-4.1 SD) with weight 12.5 kg (-3.4 SD) and head circumference 48.8 cm (-2.5 SD). Her teeth were affected by multiple caries which made chewing hard foods painful and she therefore ate only soft foods. Development was reported to be normal and she was performing well in school. Her parents had noticed loud snoring and tonsils were enlarged on examination.

She was born at term by vaginal delivery with a birth weight of 3.5kg and was the youngest of 6 children. The parents were consanguineous (first cousins) and there was a family history of short stature in distant cousins. Mother was 147 cm tall (-2.7 SD) and father 165.1 cm (-1.5 SD). There was a history of diabetes mellitus type 2, diabetic nephropathy and thalassemia in mother and the father had a history of recurrent kidney stones.

On review in the endocrinology clinic prominent forehead, depressed nasal bridge and a high-pitched voice were noted. General investigations (detailed below) were normal; however, IGF-I and IGFBP-3 concentrations were low with high basal GH and peak GH concentrations (the latter >40µg/L). The combination of low IGF-I with raised GH concentrations suggested a diagnosis of GH insensitivity. In view of the history of snoring the patient was referred to an ENT surgeon who noted large prolapsing tonsils with mild apneic episodes on sleep study. Due to the propensity of IGF-I therapy to induce tonsillar hypertrophy, she underwent tonsillectomy.

Treatment with recombinant human IGF-I was started at the age of 6 years and 1 month initially with 0.6 mg (38 mcg/kg/) BD, increasing after 1 week to 1.1 mg (70 mcg/kg) BD and then to 1.7 mg (108 mcg/kg) BD. There were no problems with hypoglycemia. Height velocity increased from 3.6 cm/year to 10.3 cm/year over the first year of treatment. Sequencing of the GH receptor identified a known intronic point (A>G) mutation between exons 6 and 7 in which leads to inclusion of a pseudoexon and an additional 36 amino acids in the extracellular domain of the GHR.

At the age of 9 years and 3 months she was noted to be at breast stage 3 and in order to preserve height potential she has been treated with GnRH analogue (Zoladex LA). The IGF-I dose has been increased to maintain dose in the range 100 – 120 mcg/kg/BD and at 10 years 3 months height is 125.8 cm (-2.1 SD) with weight 32 kg (-0.2 SD). There has been some lipophypertrophy around the injection sites and she required an adenoidectomy due to a recurrence of her snoring (with daytime somnolescence) caused by a large obstructing adenoidal pad.

Baseline Investigations

Serum electrolytes, urea, creatinine, liver function tests, calcium, phosphate, hemoglobin – all normal

Karyotype 46 XX

TSH 2.2 mU/L (0.3 -5.0) free T4 17 pmol/L (11 - 24)

Prolactin 174 mU/l (85 – 250)

IGF-I <25 ng/mL (55 – 280)

IGFBP-3 0.7 mg/L (1.5 – 3.4)

ALS 3.2 mg/L (2.3 – 11)

Fasting glucose 4.0 mmol/L Insulin 2.1 mIU/L (2.3 - 26)

Skeletal survey – no evidence of skeletal dysplasia

Bone Age delayed by 18 months

Arginine stimulation Test

Time (min) Growth Hormone (µg/L)

-15 19.3

0 4.0

15 4.8

30 14

60 >40

90 >40

120 15.6

Standard Synacthen Test

Time (min) Cortisol (nmol/L)

0 min 213

30 min 624

60 min 742

GnRH Test at age 5 years

Time LH (IU/L) FSH (IU/L)

0 <0.1 1.7

30 2.7 14

60 3.3 18

INTRODUCTION

Growth is a fundamental process of childhood. It can be divided into four phases – fetal, infancy, childhood, and pubertal growth. Although growth occurs as a continuum, the endocrine control of each phase is distinct. The fetal phase includes the fastest period of growth with a crown-rump velocity of 62cm/year during the second trimester. Growth during this phase is dependent upon placental function and maternal nutrition in addition to hormonal factors especially IGF-I, IGF-II and insulin (1,2). Although size at birth (and hence fetal growth) is profoundly affected by IGF-I deficiency during fetal life (3), the effects of congenital GH deficiency are much less marked with a mild reduction in birth size (4).

Fetal Phase

During the first year of life, growth declines from an initial velocity of around 25cm/year to around 10cm/year. Previously it has been thought that during this period growth hormone did not have a significant influence on growth however it is now clear that children with growth hormone deficiency display reduced height velocity from birth (5). In addition to growth hormone, thyroid hormone and adequate nutrition are vital for normal growth during infancy.

Infancy Phase

During the first two years of life there is a significant period of catch-up or catch-down growth so while size at birth is not well correlated with parental height, by two years of age the correlation between parental and child heights significantly improves (6). It has been hypothesized that this catch up growth is the result of a central mechanism which detects the difference between the actual and expected size and acts to increase growth velocity (7). No experimental evidence exists for this hypothesis. The second hypothesis on the origin of this catch up/down growth is that it arises from alterations in growth plate senescence. Catch down growth is associated with a reduction in the number of stem cell divisions within the growth plate while catch up growth would be due to a compensatory increase in the number of stem cell divisions within the growth plate (8).

Childhood Phase

There is a gradual transition from the infancy phase into the childhood phase of growth from 6 months to 3 years of age. Prepubertal growth velocity is relatively constant between 4-7 cm/year with the lowest growth velocity of life occurring immediately before the onset of puberty. During childhood growth is mainly controlled by the influence of the GH-IGF-I axis along with thyroid hormone.

Pubertal Growth

The final phase of growth is puberty – the period of transition from the pre-pubertal state to the full development of secondary sexual characteristics and achievement of final height. Puberty begins with the onset of activity within the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis leading to the production of androgens (in males) and estrogen (in females). In males the first sign of pubertal development is enlargement of the testes while in females it is development of breast buds. The production of androgens and estrogen is associated with an increase in activity within the GH-IGF-I axis. Administration of testosterone to boys increased both GH and IGF-I concentrations (9) but this effect is dependent upon aromatization as co-administration of an estrogen receptor antagonist (10) or administration of dihydrotestosterone (11) (the active form of testosterone that cannot be aromatized) does not lead to an increase in GH or IGF-I concentrations. In girls there is also an increase in IGF-I levels and GH secretion during puberty but the mechanisms underlying this are less clear. Administration of oral or transdermal estrogen induces a decline in serum IGF-I concentrations and a consequent increase in GH secretion (12).

Fusion of the epiphyseal growth plates is induced by the activity of estrogen on ERα as patients with mutations in the genes encoding Erα (13) or aromatase enzyme (14) result in failure of fusion of the epiphyses and tall stature.

This chapter will firstly discuss the physiology of the GH-IGF-I axis along with signal transduction of GH and IGF-I and then consider the diagnosis and treatment of growth hormone deficiency before discussing individual pathological conditions associated with both GH deficiency and GH excess. Disorders leading to GH deficiency have been divided into congenital and acquired.

GH-IGF-I AXIS

Physiology of the GH-IGF-I Axis

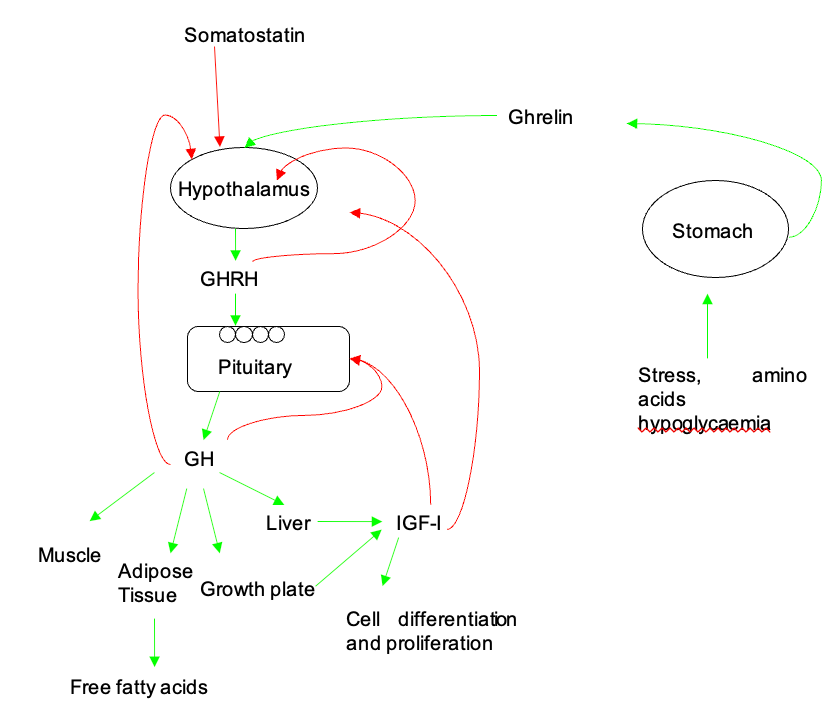

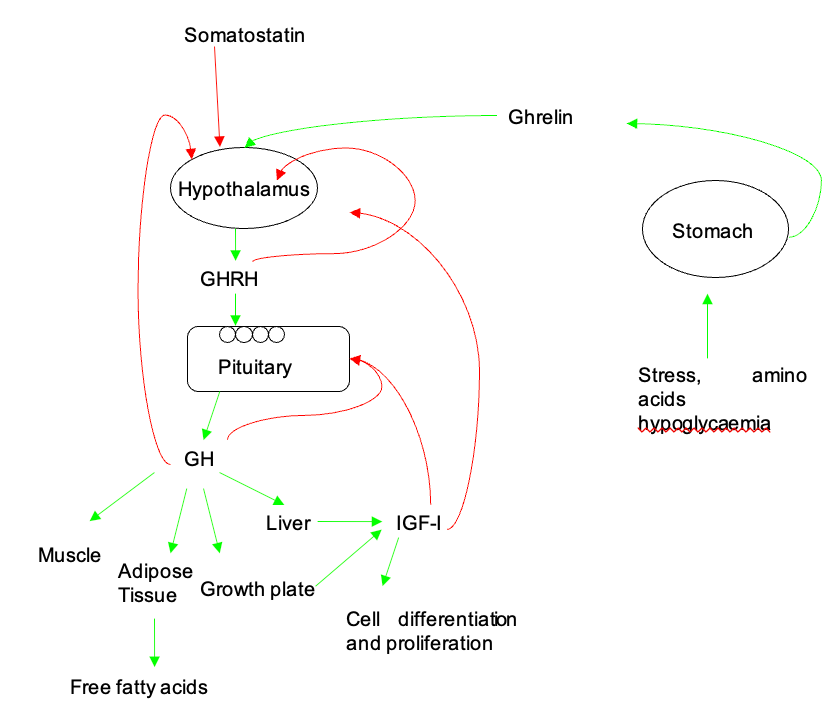

Release of Growth Hormone Releasing Hormone (GHRH) from the hypothalamus regulates the secretion of GH from the anterior pituitary both by increasing GH1 gene transcription and by promoting the secretion of stored GH. GHRH release is pulsatile and influenced by somatostatin and Ghrelin. Ghrelin is a 28 amino acid peptide produced in the stomach (15) and acts via the GH secretagogue receptor (GHSR). The active hormone is the octanoylated form produced by Ghrelin O-acetyltransferase(16) and is cleaved from the 117 amino acid preprohormone. In addition to the role in GH secretion Ghrelin also acts as an appetite stimulant (17) and stimulates the secretion of insulin (18), ACTH (19), and prolactin (19). In vivo the action of Ghrelin requires an intact GHRH system to influence GH secretion (20) but in vitro is capable of directly stimulating GH (15). Somatostatin is a peptide derived from pre-pro-somatostatin within neurons of the anterior periventricular nucleus which project to the median eminence. There are two main forms of somatostatin – 14 and 28 amino acid variants. It acts via the somatostatin receptors of which there are 5 subtypes (SSTR1-5). The anterior pituitary expresses SSTR1, 2, 3 and 5 (21). Somatostatin acts to decrease the secretion of GH by inhibiting GHRH secretion, directly inhibiting GH secretion in the anterior pituitary (22), antagonizing the activity of Ghrelin (20) as well as inhibiting its secretion (23). Somatostatin tone determines trough levels of GH and reductions in somatostatin tone are a major factor in determining the time of a pulse of GH. GH secretion is also stimulated by hypoglycemia and exercise. A summary of the factors influencing GH secretion is given in Figure 1.

GH is released from the somatotrophs of the anterior pituitary in a pulsatile manner with the pulses predominantly overnight, increasing in amplitude with age (24). The pulse amplitude is maximal in the pubertal years consistent with the raised IGF-I levels and growth velocity at this time (25). In males there is greater diurnal variation in peak amplitude, with higher peaks overnight and a lower baseline GH level compared to females. Overall GH production is higher in females. GH peak amplitude is linked to IGF-I concentrations while nadir GH is linked to waist-hip ratio (26).

Growth Hormone and GH signal Transduction

Growth Hormone (GH) is encoded by the GH1 gene located at chromosome 17q23.3 and is a 191 amino acid single chain polypeptide (27). There are 20 and 22kDa isoforms of GH generated by alternative splicing (the smaller isoform lacks amino acids 32-46) with the 20kDa accounting for around 10-20% of circulating GH (28). While GH1 is expressed within the anterior pituitary a 20kDa variant of GH is encoded by the GH2 gene but this is expressed in placenta and not in the pituitary (29).

Figure 1. Physiology of the GH-IGF-I Axis. Release of GHRH from the hypothalamus is under the control of somatostatin (inhibitory) and Ghrelin (stimulatory). Alterations in GHRH tone led to pulsatile release of GH from the anterior pituitary. GH has widespread effects on muscle, fat and in the growth plate. IGF-I is produced in liver and in local tissues in response to GH stimulation. Red lines indicate feedback loops. Figure reproduced and adapted from Butcher I Molecular and Metabolomic Mechanisms Affecting Growth in Children Born Small for Gestational Age PhD thesis University of Manchester 2013.

In the circulation GH is bound to Growth Hormone Binding Protein (GHBP). GHBP is generated either by proteolysis cleavage of the extracellular domain of the growth hormone receptor (GHR) by metzincin metalloproteinase tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme (30) or by alternative splicing of the GHR (31). The 22kDa isoform of GH has the highest affinity for GHBP with the 20kDa and placental GH having a lower affinity (32). GHBP has a molecular mass of 60kDa and acts to prolong the half-life of GH with an increase from 11 minutes to 80 minutes (33). GHBP also acts to maintain the circulating pool of GH within the vasculature (34), reducing the ability of the circulating pool of GH to bind to peripheral GHRs.

The actions of GH are mediated via the GHR, a 620 amino acid protein containing a 246-residue extracellular domain, a single24 amino acid transmembrane helix and a 350 amino acid intracellular domain. The GHR gene is located on chromosome 5p13 and contains 10 exons. The GHR exists in a pre-dimerized form on the cell surface. In contrast to previous models, it is now recognized that dimerization per se is insufficient to initiate signaling (35). GH binds to the GHR via two binding sites – initial binding is via the high affinity site 1 followed by binding to the low affinity binding site 2 (36). GH binding induces a conformational change in the dimerized GHR including rotation of one of the GHR subunits (see Figure 2). This results in locking together of the extracellular receptor-receptor interaction domain and repositioning of the box 1 motifs in the intracellular domain increasing the distance between them. In turn this leads to repositioning of tyrosine kinases, including JAK2 (37). This repositioning is crucial to JAK2 activation. In the inactive state two JAK2 molecules (each attached to one of two dimerized GHRs) are positioned so that the kinase domain of one JAK2 molecule interacts with the inhibitory pseudokinase domain of the other JAK2 molecule. After repositioning, due to the conformational change induced by GH binding, the inhibitory kinase-pseudokinase interaction is lost and the kinase domains of each JAK2 molecule interact with each other leading to JAK2 activation (38).

Activation of the GHR results in JAK2 mediated phosphorylation of the signal transducers and activator of transcription proteins (STAT), including STAT1, STAT3, STAT5A and STAT5B. STAT5A and 5B are recruited to the phosphorylated GHR where their Src homology 2 (SH2) domain is phosphorylated by JAK2. STAT5A/B then homo- or heterodimers and translocate to the nucleus (37,39) (see Figure 3). Activation of STAT1 and STAT3 is also via phosphorylation by JAK2 but this does not require recruitment to the GHR. JAK2 also phosphorylates the Src homology domain of SHC (leading to activation of the mitogen activated protein kinase pathway) and the insulin receptor substrates (IRS-1, IRS-2 and IRS-3), which, in turn activate phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and induces translocation of GLUT4 to the membrane. In addition to activation of JAK2, activation of the GHR also leads to direct activation of the Src family kinases, which are capable of activating the mitogen activated protein kinase pathway (40), and activation of protein kinase C via phospholipase C. Activation of protein kinase C stimulates lipogenesis, c-fos expression and increases intracellular calcium levels by activating type 1 calcium channels.

Figure 2. Growth hormone binding to the extracellular domain of the growth hormone receptor reorients the pre-existing homodimer so that one growth hormone receptor subunit rotates relative to the other. This structural reorientation is transmitted through the transmembrane domain resulting in a repositioning of tyrosine kinases bound to the cytoplasmic domain of the receptors. The distance between the box 1 motifs increases between inactive and active states and this movement is fundamental to activation of JAK2. Phosphorylation of JAK2 in turn leads to phosphorylation of STAT molecules, activation of the MAPK cascade and activation of IRS-1. STAT5a and STAT5b homo/heterodimerize and translocate to the nucleus. Figure kindly supplied by Dr Andrew Brooks, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland.

GH signal transduction is regulated via several mechanisms: JAK2 is autoinhibitory with the pseudokinase domain inhibiting the catalytic domain (41), SHP1 binds to and dephosphorylates JAK2 in response to GH and GH also phosphorylates the transmembrane signal regulatory glycoprotein SIRPα1 which dephosphorylates JAK2 and the GHR.

The net result of GH signal transduction is the transcription of a set of GH dependent genes and the production of IGF-I the combination of which mediates the actions of GH including effects on cell proliferation, bone density, glucose homeostasis and serum lipids.

Insulin Like Growth Factors, Their Binding Proteins and Signal Transduction

INSULIN LIKE GROWTH FACTORS

The two insulin-like growth factors, IGF-I and IGF-II, are single chain polypeptide hormones sharing 50% homology with insulin. IGF-I is a 70 amino acid 7.5 kDa protein with four domains – A, B, C and D. The prohormone also contains a c-terminal peptide that is cleaved in the Golgi apparatus before secretion. IGF-II is a 67 amino acid peptide also with a molecular weight of 7.5 kDa. The mitogenic and, in part, the metabolic effects of GH are mediated via IGF-I rather than IGF-II. The IGFs circulate bound to the IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs), of which there are six classical high affinity IGFBPs. The IGFs form a ternary complex with an IGFBP and the Acid Labile Subunit (ALS), an 85kDa protein secreted by the liver. 99% of serum IGF-I is bound to a ternary complex which acts to prolong the half-life of IGF-I (42). IGF-I is produced in both the liver and in peripheral tissues and thus can act in an autocrine and paracrine manner.

IGF RECEPTORS

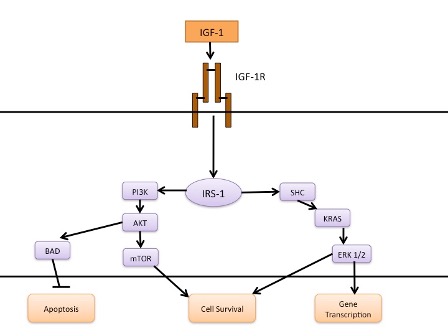

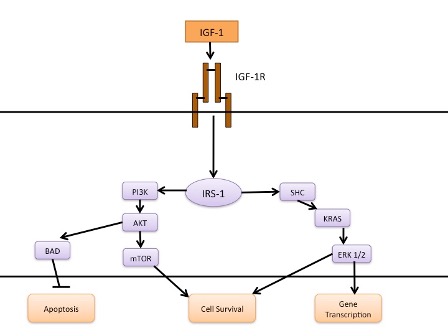

The IGF-1R is a transmembrane heterotetramer consisting of consisting of two extracellular α chains and two membrane-spanning β chains linked by several disulphide bonds (43). Ligand binding sites are present in the α subunits while the β subunits contain the juxtamembrane domain, tyrosine kinase domain and a carboxy terminal domain (44). Ligand binding to the α subunit activates the intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity of the β subunit which leads to autophosphorylation of tyrosine kinases in the juxtamembrane, tyrosine kinase and carboxy terminal domains. This autophosphorylation provides docking sites for substrates including the insulin receptor substrates (IRS-1, -2, -3, -4) and Shc. IRS-1 and Shc recruit the growth factor receptor bound protein 2 that associates with son of sevenless to activate the MAPK pathway. IRS-1 also activates PI3K via its regulatory subunit, p85, leading to activation of AKT which phosphorylates BAD and activates mTOR leading to inhibition of apoptosis and stimulation of proliferation. A summary of IGF-I signal transduction is given in Figure 3.

Mouse studies have delineated the relative contribution to growth of the GH-IGF system – deletion of Igf1 or Igf2 results in a 40% reduction in birth weight with a reduction of 55% where Igf1r is deleted (45). Deletion of Igf1 with Igf1r or Igf2 leads to a 70% reduction in birth weight and death from respiratory distress at birth (45) whereas the Igf2r appears to negatively regulate growth as deletion of this gene results in an increase in size to 130% of wild type. IGF-I is produced in both the liver and in peripheral tissues and thus can act in an autocrine and paracrine manner. It appears that autocrine/paracrine IGF-I is more important for growth than liver derived IGF-I as a hepatic specific deletion of Igf1 in mouse resulted in no impairment of growth despite a 75% reduction in serum IGF-I concentrations (46) while a triple liver specific deletion of Igf1/Igfals/Igfbp3 resulted in a 97.5% reduction in circulating IGF-I concentrations with a 6% decrease in body length (47).

Figure 3. IGF-I Signal Transduction. Binding of IGF-I leads to phosphorylation and activation of IRS-1 which, in turn, activates the PI3K and MAPK pathways.

DIAGNOSIS OF GROWTH HORMONE DEFICIENCY IN CHILDHOOD

The diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency in childhood is multifactorial process and includes 1) auxological assessment 2) biochemical tests of the GH-IGF-I axis and 3) radiological evaluation of the hypothalamus and pituitary (normally with MR imaging). Prior to evaluation of the GH-IGF-I axis in a short child other diagnosis such as familial short stature, hypothyroidism, Turner syndrome, chronic illness such as Crohn’s disease and skeletal dysplasias should be considered and evaluated appropriately. Patients to be evaluated for growth hormone deficiency include (48,49):

- Severe short stature (defined height >3 SD below mean)

- Height more than 1.5 SD below mid parental height

- Height >2 SD below mean with height velocity over 1 year >1 SD below the mean for chronological age or a decrease of more than 0.5 SD in height over 1 year in children aged >2 years

- In the absence of short stature – a height velocity more than 2 SD below mean over 1 year or >1.5 SD below mean sustained over 2 years

- Signs indicative of an intracranial lesion or history of brain tumor, cranial irradiation, or other organic pituitary abnormality.

- Radiological evidence of a pituitary abnormality

- Signs and/or symptoms of neonatal GHD

Etiology

Disorders of GH can be divided into those that cause growth hormone deficiency or growth hormone excess. In childhood growth hormone deficiency is rare with an incidence of 1 in 4000 while the incidence of childhood GH excess is not known but only around 200 cases have been reported in the literature (50). Causes of GH deficiency are listed in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Causes of Growth Hormone Deficiency

|

|

Cause

|

Examples

|

|

Idiopathic

|

|

|

Genetic

|

GHRHR mutations

GH1 mutations

|

|

Structural brain malformations

|

Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome

Rathke’s cyst

Agenesis of corpus callosum

Septo-optic dysplasia

Holoprosencephaly

|

|

Midline Tumors

|

Craniopharyngioma

Optic nerve Glioma

Germinoma

Pituitary adenoma

|

|

Cranial Irradiation

|

|

|

Traumatic Brain Injury

|

Road Traffic Accident

|

|

CNS infections

|

|

|

Inflammation and Auto-immunity

|

Sarcoidosis

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Hypophysitis

|

|

Psychosocial deprivation

|

|

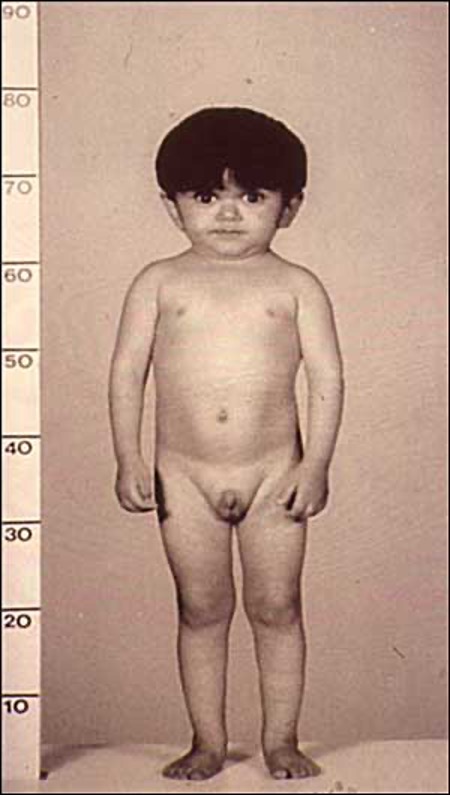

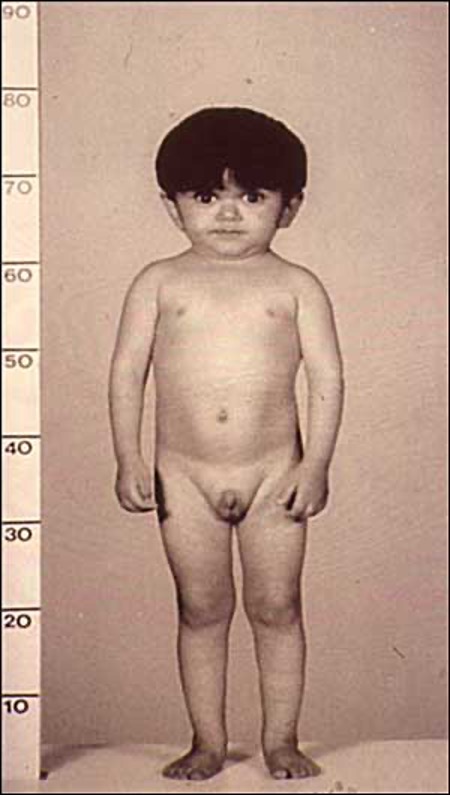

Clinical Presentation of GH Deficiency

GH deficiency can present either in isolation (isolated GHD - IGHD) or in combination with other pituitary hormone insufficiencies (multiple pituitary hormone deficiency - MPHD). In the neonatal period MPHD typically presents with reduced penile size, episodes of hypoglycemia, and prolonged unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. MPHD is associated with breech delivery, adverse incidents in pregnancy, and admission to the newborn intensive care unit (51). Children with severe growth hormone deficiency often appear young for their age and have midface hypoplasia and increased truncal adiposity (see Figure 4). The major clinical feature of GH deficiency is growth failure; typically, this occurs after the first year of life but may be apparent earlier in severe GHD. The earliest manifestations are a reduction in height velocity followed by a reduction in height standard deviation score (SDS) adjusted for mean parental height SDS. The child’s height SDS will ultimately fall below -2SD with the time taken to achieve this depending on the severity and duration of GHD.

Figure 4. Child with Laron syndrome. Short stature with typical facial appearance of GH insensitivity with midface hypoplasia, this finding is common to GH deficiency as well.

Biochemical Assessment of the GH-IGF-I Axis

Multiple assays have been developed to measure GH in serum. A consensus statement of the GH-IGF-I research society in 2000 recommended that assays used should use monoclonal antibodies to measure the 22kDa variant of human GH and that the reference preparation should be the WHO standard 88/624 (a recombinant human 22kDa GH at 3 IU = 1mg) (48,52).

Growth Hormone Stimulation Tests and GH Profiles

A number of growth hormone stimulation tests have been developed and can be divided into screening tests or definitive tests. Screening tests include exercise, fasting, levodopa, and clonidine and are characterized by low toxicity, ease of administration but low specificity. Definitive tests include the insulin tolerance test, glucagon, and arginine stimulation tests. Using the auxological criteria above a peak GH concentration below 10µg/L has traditionally been used to support the diagnosis of GHD. GHD is not a dichotomous state but exists as a continuum from severe GHD to normality and there is known to be an overlap in peak GH concentrations between normal children and those with GHD. For this reason, and due to the advent of more sensitive monoclonal antibodies based on the recombinant human GH reference standard, some units will use a more stringent cut-off for the diagnosis of GHD e.g., 7µg/L. Where the diagnosis is isolated idiopathic GHD two pharmacological tests are required. Only one provocative test of GH secretion is required in children with one or more of the following criteria:

- Central nervous system pathology affecting the pituitary or hypothalamus

- A history of cranial irradiation

- An identified pathological genetic variant known to be associated with GHD

- Multiple pituitary hormone deficiency

INSULIN TOLERANCE TEST

The gold standard test is considered to be the Insulin Tolerance Test. This test relies upon an intravenous dose of insulin to induce hypoglycemia with a subsequent rise in GH expected as part of the counter regulatory response to hypoglycemia (53). Cortisol secretion also rises in response to hypoglycemia and thus this test also assesses the hypothalomo- pituitary-adrenal axis. The patient is required to fast overnight and, in the morning, a reliable intravenous line is inserted following which an insulin dose of 0.1units/kg is administered. The dose is reduced to 0.05 units/kg in children under 4 and where there is known or likely multiple pituitary hormone deficiency. This test is generally not recommended for infants and in this group the dose of insulin would be reduced further to 0.01units/kg. After administration of insulin there is careful bedside monitoring of blood glucose concentration and once the blood glucose has reached <2.6 mmol/L (47 mg/dL) the patient eats a high carbohydrate meal. Administration of 10% glucose at 2ml/kg may be required in order to restore adequate blood glucose concentrations. This should be prepared in advance of the start of the test along with an appropriate dose of IV hydrocortisone (this should be given after hypoglycemia where there is known adrenal insufficiency or where hypoglycemia is more severe or prolonged than expected). 50% dextrose is recommended by some for the correction of hypoglycemia during the test but administration of such hyperosmolar solutions has been associated with adverse outcome (54) including cerebral edema. Due to the risks associated with this test it should only ever be performed in a center with appropriate experience.

GLUCAGON TEST

The glucagon test is one of a number of safer alternative GH provocation tests. Intramuscular administration of glucagon leads to an increase in GH due to a rise in insulin levels compensating for the increase in serum glucose (55). Maximum GH peak occurs 2-3 hours after injection of glucagon. Although less common than with the insulin tolerance test hypoglycemia can occur with the glucagon stimulation test where there is an excessive insulin response. There should therefore be blood glucose monitoring throughout the test and a meal consumed at the end of the test. Nausea and vomiting are other common side effects.

ARGININE STIMULATION TEST

Arginine administration stimulates the release of GH by inhibiting somatostatin release. Following an overnight fast arginine is administered intravenously at 0.5g/kg (maximum dose 30g) over 30 minutes. Unlike glucagon or insulin, arginine does not directly cause hypoglycemia and thus the arginine stimulation test may be safer, particularly for those patients with predisposition to hypoglycemia. Examples of patients where an arginine test would be suitable where the insulin or glucagon-based tests would not be suitable include patients with diabetes and a history of seizures or children with disorders of cerebral glucose uptake (GLUT2 deficiency) where the patient should be continuously ketotic. Arginine can be combined with L-dopa or GHRH. For combined tests, particularly the arginine-GHRH test it is important to have a test specific cut off for the diagnosis of GHD as with a powerful stimulus of GH secretion a higher cut off is required (a normal peak GH response for arginine-GHRH has been defined at 19-120 µg/L(56)). GHRH can be used on its own as a provocative agent but is greatly affected by variations in somatostatin tone leading to a highly variable response. In addition, false negative tests may occur in children with hypothalamic damage.

Oral agents used in GH stimulation tests include clonidine and L-Dopa. Both clonidine and L-Dopa act by increasing adrenergic tone to increase GHRH and decrease somatostatin levels. A fast of 6 hours is required prior to the test. Since clonidine is a drug used to lower blood pressure hypotension is a potential side effect. Drowsiness is also a frequent occurrence during this test.

INTERPRETATION

Significant problems exist with GH stimulation tests – peak GH varies according to the stimulus used (57), false positive results in normal pre-pubertal children are frequent (56), the tests have poor reproducibility and there is also variability in GH level with GH assay used (58). Peak GH is also reduced in obesity and for adults BMI specific cut-offs for the diagnosis of GHD have been developed (59).

Low GH levels to provocation tests frequently occur in the immediate peripubertal period. Given the known action of the sex steroids to augment endogenous GH secretion this has led some pediatric endocrinologists to prime children of peripubertal age but without clinical signs of puberty undergoing GH stimulation testing with exogenous sex steroids (diethylstilbestrol, ethinylestradiol and testosterone can be used). Around 50% of pediatric endocrinologists routinely use priming for GH stimulation tests(60). Some endocrinologists will prime boys >9 years and girls >8 years others will prime only those with a delayed puberty >13-14 years in boys and > 11 or 12 years in girls. In one study by Marin et al(61) where 61% of healthy prepubertal children failed to demonstrate a peak GH >7µg/L to three GH provocative tests (exercise, insulin and arginine) but after administration of estrogen 95% of these children demonstrated a peak GH >7 µg/L. Multiple other studies have confirmed this result in healthy peripubertal children with growth impairment (62). Thus, the argument in favor of priming is that it prevents false positive diagnoses of GHD in this group. The concerns about priming are that it only briefly augments the GH response which then returns to suboptimal levels which may be insufficient for normal growth. Thus priming may result in failure to treat children with transient peripubertal GH deficiency who would have benefitted from treatment (62).

24 hour or overnight 12-hour GH profiles with measurement of serum GH every 20 minutes have been proposed as an alternative assessment of GH secretion. The obvious disadvantages are the large number of samples required and costs, particularly of the overnight hospital admission. While a 24 hour GH profile has a high reproducibility there is also a large degree of inter individual variability limiting the usefulness of the procedure as a diagnostic test (63).

A diagnosis of GH neurosecretory dysfunction can be made where the patient presents with signs/symptoms of GHD with low IGF-I concentration, a normal peak GH level to pharmacological stimulation but absence of spontaneous GH peaks on 24 hour serum GH profile (64). This diagnosis has not been identified in adults and given the interindividual variability in 24-hour GH profiles caution should be made before coming to GH neurosecretory dysfunction as a diagnosis, particularly where there is no history of cranial irradiation.

Measurement of IGF-I and/or IGFBP-3

IGF-I and IGFBP-3 are, unlike GH, present at relatively constant concentrations in serum throughout the day and can therefore be measured by a simple blood test without the need for pharmacological stimulation. IGF-I is suppressed in states of poor nutrition and both IGF-I and IGFBP-3 concentrations vary with age and pubertal stage, thus normative ranges taking into account age, Tanner stage, and BMI have been recommended (52). The majority of IGF-I exists bound in the ternary IGF-I/IGFBP-3/ALS complex (thus free IGF-I is very low and difficult to measure) and assays therefore require a step to remove the IGF binding proteins before measurement of total IGF-I. Incomplete removal of IGF-I can potentially lead to false low IGF-I concentrations. Both IGF-I and IGFBP-3 have a low sensitivity (~50%) with a high specificity (97%) (65,66) and thus are of limited value in isolation. They do, however, form a vital component of the assessment of a child for GHD combined with auxological, other biochemical and radiological data.

Neuroimaging

Identifying abnormalities of the hypothalamo-pituitary axis provides powerful evidence for the diagnosis of GH deficiency in the short child. The most common abnormality identified in congenital GHD is the so-called pituitary stalk interruption syndrome consisting of a variable combination of anterior pituitary hypoplasia, ectopic posterior pituitary, and thinning or interruption of the pituitary stalk (67). Loss of the vascular pituitary stalk increases the risk of MPHD 27-fold but required gadolinium-DTPA administration to reliably distinguish presence/absence of vascular stalk (68). Other potential findings in congenital GHD include

- Septo-optic dysplasia – combination of absence of septum pellucidium, optic nerve hypoplasia and hypopituitarism. May be associated with an ectopic posterior pituitary and anterior pituitary hypoplasia.

- Abnormalities of the corpus callosum – agenesis, corpus callosum cysts

- Holoprosencephaly

- Eye abnormalities – microphthalmia or anophthalmia (GLI2 or OTX2 mutations)

- Absent olfactory bulbs (FGFR1, FRF8 and PROKR2 mutations)

- Pituitary hyperplasia (seen in patients with PROP1 mutations)

- Hypothalamic hamartoma (Pallister-Hall syndrome)

- Empty sella

- Absence of the internal carotid artery

- Arnold-Chiari malformations

- Arachnoid cysts

- Syringomyelia

In acquired GHD tumors affecting the hypothalamo-pituitary axis will frequently be identified – craniopharyngiomas, adenomas, and germinomas. Thickening of the pituitary stalk may be identified in Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

As well as a role in the diagnosis of GH deficiency MR imaging can also help predict which patients will require re-testing of growth hormone status at the end of growth. Young adults with MRI abnormalities have an increased risk of persisting GHD into adulthood (69).

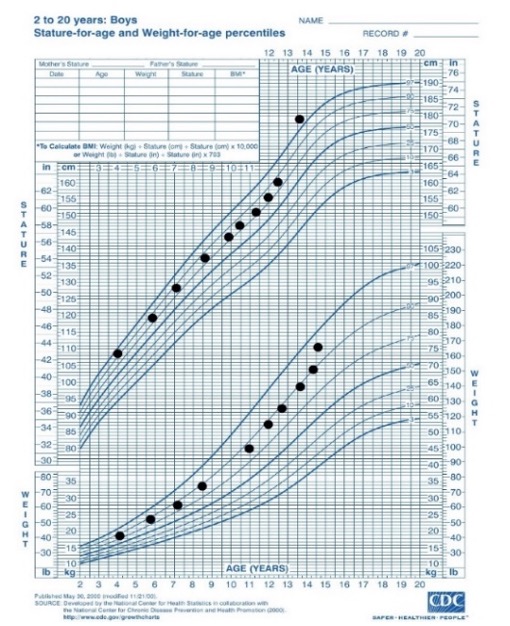

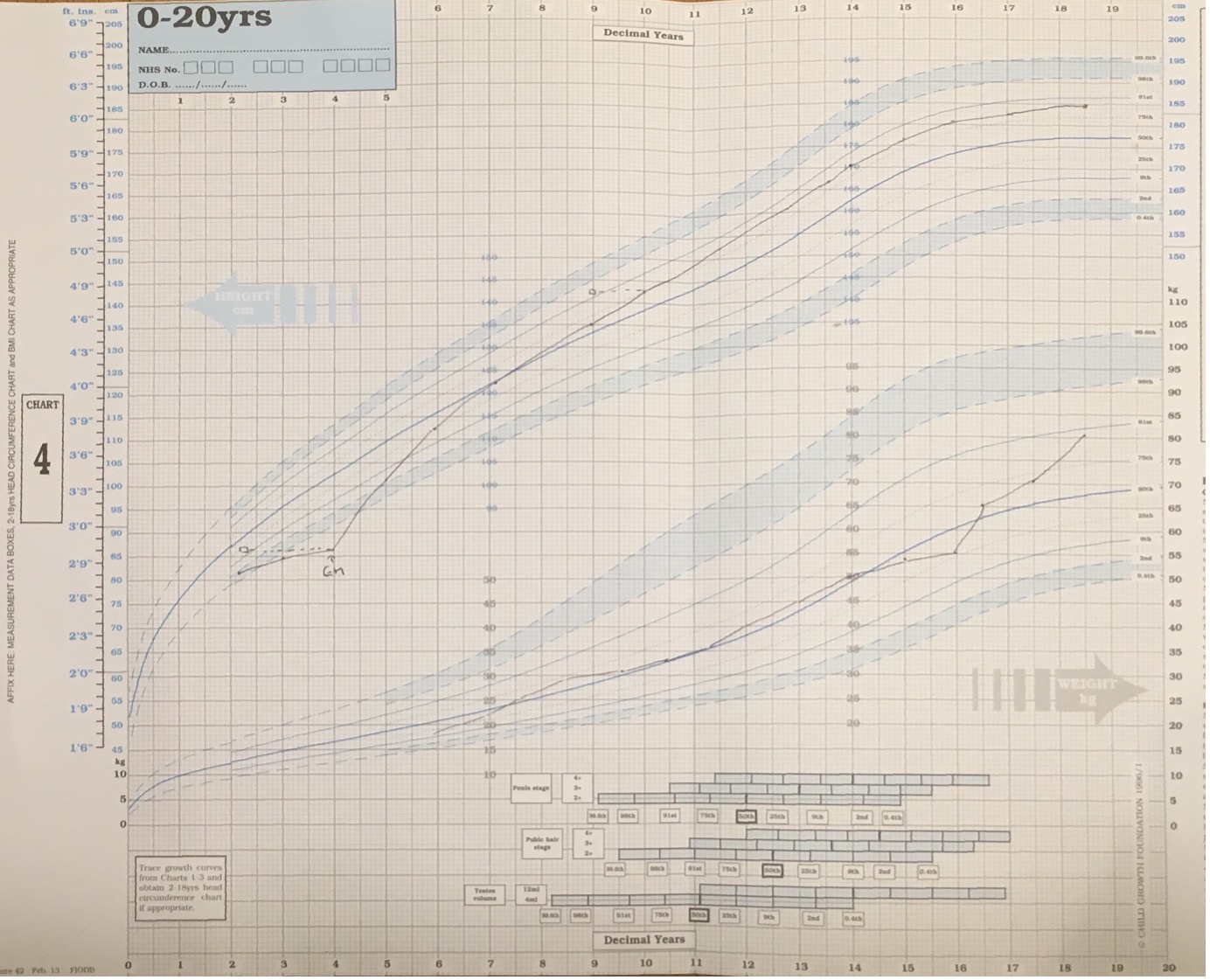

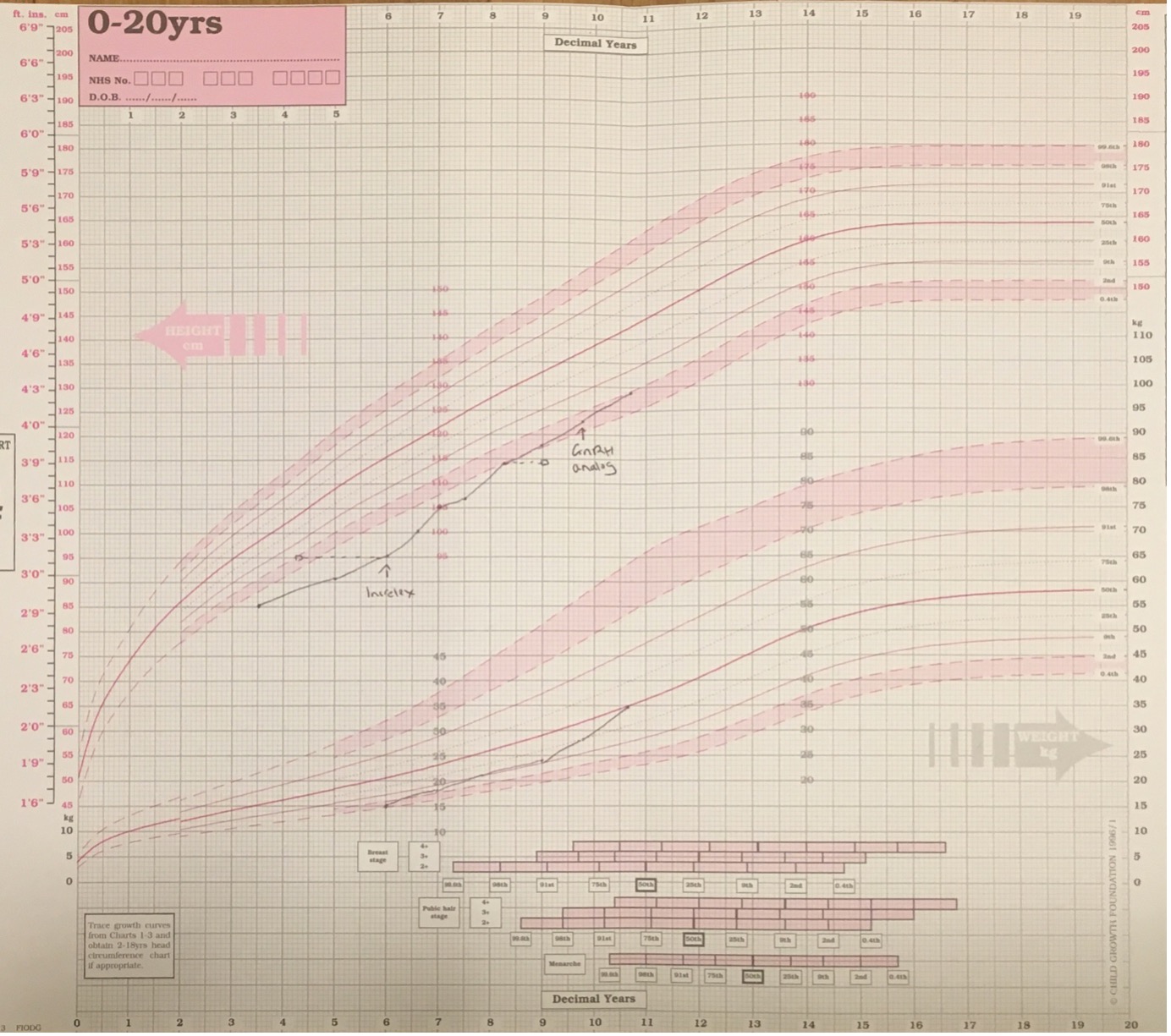

GH Therapy

All children diagnosed with GH deficiency should be treated with recombinant human growth hormone as soon as possible after the diagnosis is made. The aim of treatment is to normalize height – both to within the normal range for the population and to achieve a height within the child’s target range. GH is administered as a once daily subcutaneous injection in the evening. Starting dose is usually in the range of 25-35µg/kg/day with maximum dose being 50µg/kg/day. In children with more severe GHD (evidence by a lower peak GH level, more severe presentation, MRI abnormality) the response to GH is better and often height can be normalized with lower doses of GH e.g., 17-35 µg/kg/day (70). Prediction models (discussed below) are available and in GHD have been shown to reduce variability in response but do not improve height gain (71). Children receiving GH therapy should be seen every 3-6 months and the GH dose titrated to height velocity and height gain. Monitoring of IGF-I concentrations is recommended to avoid prolonged periods of supraphysiological IGF-I levels. In general, IGF-I should be measured at least annually but can be measured more frequently particularly where there has been a recent increase in dose. A reduction in dose would normally be considered were two consecutive IGF-I levels were above +2 SD. As a guide to dose adjustment a 20% alteration in dose leads, on average, to a 1 SD change in IGF-I concentration (72). Treatment is continued until the child is post-pubertal and growth is either completely ceased or is <2cm per year. A growth chart from a child with congenital GHD treated with recombinant human GH therapy is shown in Figure 5.

Currently there is no single accepted definition of poor response to GH treatment with suggestions including change in height SDS <0.3 or 0.5 during the first year of treatment, change in height velocity <+3cm/year during 1st year of treatment, change in height velocity <+1SD or a height velocity <-1 SD during the first year of therapy. Depending on the definition used 20-35% of patients display a poor response (73). It is important to discuss the possibility of a poor response with the family prior to staring therapy.

Figure 5. Growth Chart from child with GH deficiency. GH therapy is started at age 4 with height SDS -3.7 SD. There is a sustained improvement in height velocity leading to a final height of +1.5 SD.

Multiple long-acting preparations of growth hormone are at various stages of development (74). A phase three trial in adults with GHD have been completed and has demonstrated similar efficacy with a once weekly injection of a long-acting GH compared to conventional daily GH (75). Trials in children are currently ongoing.

Prediction of Response to GH Therapy and the d3-Growth Hormone Receptor Polymorphism

Initial work predicting the response to GH therapy was based on auxological and biochemical data, particularly from the Kabi International Growth Study (KIGS), a large surveillance study of over 62,000 patients treated with GH in childhood. Prediction models developed included models for idiopathic isolated GH deficiency (76) and early onset isolated GH deficiency (77). For the idiopathic isolated GH deficiency prediction model the model explained 61% of the variability on GH response. Factors included in the prediction model were peak GH during stimulation test, age at start of GH therapy, height SDS minus mean parental height SDS, growth hormone dose and weight SDS. Other prediction models derived from alternative datasets have also been produced for GHD (78,79).

Around 50% of the European population are homo- or heterozygous for a polymorphism of the GHR that leads to deletion of exon 3 and 22 amino acid residues near the N-terminal. In 2004 it was reported that GH signaling via the GHR with the d3 was increased and that children treated with GH under the SGA license or with idiopathic short stature showed an increased first year growth velocity where they were homo- or heterozygous for the d3 polymorphism (80). Since this original report there have been many studies assessing the effect on the d3 polymorphism on response to GH therapy in GH deficiency, Turner syndrome, SGA children and in children with idiopathic short stature. A meta-analysis of these studies in 2011 indicated that, compared to children homozygous for the full-length allele, children homozygous for the d3 polymorphism have an increase in 1st year height velocity SDS of 0.14 SD and children heterozygous for the d3 polymorphism has an increase of 0.09 SD (81). Thus, it appears that the d3 polymorphism has a modest effect mediating the response to GH therapy.

The PREDICT study was a large international observational study which assessed the contribution of single nucleotide polymorphisms in over 100 candidate genes to GH response in a cohort of children with GH deficiency or Turner syndrome (82,83). GH response was assessed by change in IGF-I concentrations over 1 month and by height velocity change over the first year of treatment. Carriage of 10 polymorphisms within 7 different genes, related in particular to cell signaling, were identified to be associated with change in IGF-I over the first month of GH treatment and height velocity over the first year of treatment. In addition to assessing association between genotype and response to GH therapy the PREDICT study also assessed the use of basal gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells to predict GH response. There were 1188 genes where the expression level was associated with low response and 865 genes where expression level was associated with a high response to GH therapy (83). Network analysis of the human interactome associated with these genes indicated that glucocorticoid, estrogen, and insulin receptor signaling, and protein ubiquitination pathways were most represented by the genes where association was linked to high or low response to GH therapy.

A recent genome wide association study examining GH responsiveness did not identify any significant SNPs in their primary analysis (the primary analysis utilized all diagnostic groups for GH treatment together) (84). They did identify 4 SNPs in a secondary analysis stratifying by diagnosis and limiting to European ancestry – the closest associate genes are UBE4B, LAPTM4B, COL1A1/NT5DC1 and CLEC7A/OLR1(84).

INHERITED DISORDERS OF THE GH-IGF-I AXIS

Genetic Disorders Causing Isolated Growth Hormone Deficiency

Initial reports suggested that only around 12% of cases of isolated growth hormone deficiency were associated with abnormalities of the hypothalamus or pituitary on MR imaging (85). More recent studies have indicated that up to 26% of cases of isolated GHD are associated with MR abnormalities (86), particularly anterior pituitary hypoplasia and ectopic posterior pituitary. Within the remaining cohort of patients with IGHD an increasing number of genetic causes have been identified.

IGHD TYPE 1

IGHD type 1a is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner and is due to homozygous deletions and nonsense mutations in the GH1 gene leading to a complete absence of the GH protein from serum. The clinical presentation is with severe growth hormone deficiency and growth failure from 6 months of life with height SDS >4.5 SD below mean. Typically patients respond well to initial therapy with GH but then develop anti-GH antibodies leading to a loss of efficacy (87). Treatment with IGF-I is an option for such patients.

IGHD type 1b is also autosomal recessive and caused by mutations in the GH1 gene – either mis-sense, splice site or nonsense or by mutations within the GHRHR (the gene encoding the GHRH receptor). The clinical phenotype in IGHD type 1b is milder than that of IGHD 1a with the presence of low but detectable levels of GH to stimulation tests. These patients show a good response to treatment with GH without the development of anti-GH antibodies.

The GHRHR is a 423 amino acid G-coupled protein receptor. It contains seven transmembrane domains encoded for by a 13-exon gene on chromosome 7p15. While human mutations leading to isolated GH deficiency have been found in the GHRHR gene, to date no such mutations have been identified in the gene encoding the ligand, GHRH. The initial link between a GHRHR mutation and impaired growth was in the little mouse, where Lin et al identified an amino acid substitution in codon 60 of the mouse GHRHR (88). The substitution of glycine for aspartic acid (D60G) prevented the binding of GHRH to the mutant receptor. Subsequent to the identification of the mutation in mouse a nonsense mutation (p.E72X) was identified in two patients in a consanguineous family of Indian ethnic origin (89). Since this initial report multiple families have been reported and splice site mutations, missense mutations, nonsense mutations, microdeletions and one mutation in the promoter (90). The clinical phenotype of an individual with a GHRHR mutation is that of autosomal recessive inheritance of IGHD, anterior pituitary hypoplasia (defined as pituitary height more than 2 SD below mean), GH concentrations are either undetectable or very low in response to provocation tests and IGF-I/IGFBP-3 levels are low. In contrast to patients with GH1 mutations midface hypoplasia, neonatal hypoglycemia and microphallus are less common. Intelligence is normal and affected individuals are fertile.

Expression of GHRHR is upregulated by the pituitary transcription factor POU1F1 and this results in somatotroph hypertrophy. Because of this effect on somatotrophs anterior pituitary hypoplasia is commonly seen on MR imaging but there have been reports of GHRHR mutations with normal pituitary morphology (91).

IGHD TYPE 2

IGHD Type 2 is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in the GH1 gene. The severity of GH deficiency is highly variable. While the name of the condition suggests only GH is affected, in practice loss of other pituitary hormones has been reported and patient must be followed up to identify these additional hormone deficiencies. Loss of TSH, ACTH, prolactin and gonadotrophins have all been reported (92).

IGHD type 2 is most commonly caused by mutations that affect splicing of GH1, particularly splicing of exon 3 (93). The most frequent mutations are within the first six bp of the exon 3 donor splice site (93) but mutations in the exon 3 splice enhancers and intron splice enhancers have also been reported (90). The exon 3 splice mutations lead to the exclusion of exon 3 and the production of a 17.5kDa isoform of GH lacking amino acids 31-71, responsible for connecting helix 1 and helix 2 of the mature GH molecule. This abnormal 17.5 kDa variant GH is retained within the endoplasmic reticulum, disrupts the Golgi apparatus and reduces the stability of the 22kDa GH isoform (94). In addition to GH trafficking of other hormones including ACTH is disrupted. A mouse model overexpressing the 17.5kDa isoform demonstrated anterior pituitary hypoplasia with invasion by activated macrophages. The loss of additional pituitary hormones is likely to result from the disrupted hormone trafficking as well as the pituitary inflammation and destruction. Children with IGHD type II may display anterior pituitary hypoplasia on MR imaging. Currently there is no specific treatment in man to ameliorate the effects of the 17.5kDa isoform. A small interfering RNA based therapy has been successful in the mouse model of IGHD type 2 (95) but the delivery system used involved inserting the short hairpin RNA as a transgene. Successful implementation of such a therapy in humans will require an alternative mode of delivery capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier. As well as the classical exon 3 splice site mutations IGHD type 2 is also caused by missense mutations. These have been reported to lead to impaired GH release (96) or to alter folding of GH (97).

IGHD TYPE 3

IGHD Type 3 is of x-linked recessive inheritance and the males described were both immunoglobulin and GH deficient. A single patient has been reported with a mutation in the BTK gene (resulting in exon skipping) with x-linked agammaglobulinemia and GH deficiency (98).

One family has been reported with isolated GHD caused by mutations in RNPC3 (99). The three affected sisters had compound heterozygous mutations in RNPC3 (p.P474T and p.R502X) and presented with classical severe isolated GHD with anterior pituitary hypoplasia on MR imaging. RNPC3 encodes a component of the minor spliceosome responsible for splicing of a small subset (<0.5%) of introns which are present in ~3% of human genes. Given that splicing is an essential basic process present in all tissues it is interesting that the phenotype seen is pituitary specific. The patients displayed relatively minor perturbations in splicing which is hypothesized to be tolerated in most tissues, but not in the developing pituitary. Response to GH treatment is reported to be excellent (100).

Genetic Disorders Leading to Abnormal Pituitary Development and Multiple Pituitary Hormone Deficiency

Mutations in an increasing number of genes lead to loss of multiple pituitary hormones including growth hormone (summarized in Table 2). A brief summary of each is given below – for an extensive review of pituitary development and it’s genetic control see Bancalari et al (101).

HESX1

The paired homeobox domain protein HESX1 is one of the earliest specific markers of the pituitary primordium and it acts as a transcriptional repressor. Mutations in HESX1 are associated with septo-optic dysplasia (102) and MPHD (103,104) which can be inherited in an autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant pattern. In addition to the MRI appearances associated with septo-optic dysplasia patients with HESX1 mutations can have an ectopic posterior pituitary (104).

OTX2

The OTX2 homeobox gene is a homologue of the Drosophila orthodenticle protein. It is expressed early in gastrulation and is involved in development of the central nervous system and eye. In humans OTX2 mutations have been identified in patients with anophthalmia or microphthalmia with isolated GHD or MPHD (105). On MR imaging an ectopic posterior pituitary and small anterior pituitary have been associated with OTX2 mutations.

SOX3

SOX3 is a single exon gene located on the X chromosome, is expressed widely throughout the ventral diencephalon and is involved in the development of Rathke’s pouch (106). In humans SOX3 duplications (107) or polyalanine expansion (108,109) have been associated with X-linked hypopituitarism with or without mental retardation. The pituitary phenotype is variable from isolated GHD to MPHD. MRI findings may include anterior pituitary hypoplasia, ectopic posterior pituitary, and corpus callosum abnormalities.

PITX2

PITX2 is a homeodomain transcription factor expressed in the rostral brain and oral ectoderm during development and throughout the anterior pituitary in adult life. Axenfeld-Riegler syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by ocular, dental and craniofacial abnormalities in addition to pituitary abnormalities. Mutations in PITX2 have been found in patients with Axenfeld-Riegler syndrome and GH deficiency (110).

LHX3 and LHX4

LHX3 and LHX4 encode LIM domain proteins expressed in Rathke’s pouch involved in transcriptional regulation. Homozygous loss of function mutations in LHX3 have been associated with hypopituitarism, sensorineural deafness and cervical abnormalities (rigid cervical spine and cervical spina bifida occulta) (111,112). The MRI appearance may be of a small or enlarged pituitary or a hypointense lesion compatible with a microadenoma. Mutations in LHX4 lead to a range of pituitary dysfunction from GHD to MPHD (113) with a pituitary phenotype including anterior pituitary hypoplasia, ectopic posterior pituitary and in one family there was pointed cerebellar tonsils suggestive of an Arnold Chiari Malformation (114).

GLI2

GLI2 is a mediator of Sonic Hedgehog signal transduction and is expressed in the oral ectoderm and ventral diencephalon. Heterozygous mutations in GLI2 lead to a variable combination of holoprosencephaly and hypopituitarism (115,116). Other clinical findings may include a cleft lip/palate, postaxial polydactyly and anophthalmia.

FGFR1, FGF8 and PROKR2

FGFR1, FGF8 and PROKR2 were previously known to be involved in the pathogenesis of Kallmann syndrome (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with anosmia). Screening of a cohort of 103 patients with hypopituitarism identified mutations in these Kallmann syndrome genes in eight patients (FGFR1 n=3, FGF8 n=1, PROKR2 n=4) (117). An EPP was identified in one patient with an FGFR1 mutation and a hypoplastic anterior pituitary in one patient with a PROKR2 mutation.

PROP1

Prophet of Pit-1 (PROP1) is a homeodomain transcription factor with expression limited to the anterior pituitary. It acts as a transcriptional repressor downregulating HESX1 and as an activator of POU1F1. PROP1 mutations are associated with GH, prolactin, TSH and LH/FSH deficiency with rare cases of ACTH deficiency. PROP1 mutations are the commonest genetic cause of hereditary MPHD accounting for ~50% of familial cases (117). MRI findings include both small and large anterior pituitary glands and even extension of the pituitary to form a large suprasellar mass which waxes and wanes before involuting (118). Gonadotrophin deficiency in patients with PROP1 mutations is highly variable and can present with micropenis and cryptorchidism to delayed pubertal onset potentially indicating a role of PROP1 in maintenance of gonadotrophin function.

POU1F1

The first genetic cause of multiple pituitary hormone deficiency, identified in 1992, was mutations in the POU1F1transcription factor (119). It is essential for the development of somatotrophs, lactotrophs, and thyrotrophs, consequently mutations in POU1F1 lead to deficiency of GH, TSH and prolactin. Anterior pituitary size is most often small but can be normal with normal stalk and normally sited posterior pituitary. The hormone deficiencies can present at any time from birth to adolescence.

IGSF1

Mutations in IGSF1 (immunoglobulin superfamily member 1) were identified initially as a cause of central hypothyroidism and macro-orchidism (120). IGSF1 is a membrane glycoprotein expressed in Rathke’s pouch. The identified mutations lead to aberrant protein trafficking and protein mislocalisation. In a small number of subjects mild or transient GHD has been identified (121,122). It is clear that the immunoglobulin superfamily of proteins may have a wider role in controlling pituitary hormone secretion with mutations in immunoglobulin superfamily member 10 associated with constitutional delay in growth and puberty (123).

ARNT2

A single family with a homozygous frameshift loss of function mutation in ARNT2 has been described. The affected individuals demonstrated multiple pituitary hormone deficiency including diabetes insipidus along with post-natal microcephaly, frontal and temporal lobe hypoplasia, seizures, developmental delay, visual impairment and congenital abnormalities of the urinary tract (124). ARNT2 is a HLH transcription factor which is known to dimerize with SIM1, a known regulator of neuronal differentiation.

TCF7L1

Transcription factor 7-like 1 is a regulator of WNT/β-catenin signaling and is expressed in the developing forebrain and pituitary. Two patients with heterozygous missense variants have been reported – one diagnosed with GHD and one with low IGF-I concentrations (124). MRI findings are listed in Table 2. In both families there were unaffected family members also carrying the variant. Given functional studies confirmed the deleterious nature of the variant this is likely to represent autosomal dominant inheritance with variable penetrance.

RAX

RAX encodes a transcription factor involved in eye and forebrain development. A child with a homozygous frameshift truncating mutation in RAX has been identified with a phenotype including anophthalmia, bilateral cleft lip and palate with congenital hypopituitarism (125).

LAMB2

Laminin b2 is a basement membrane protein with autosomal recessive mutations associated with congenital nephrotic syndrome, ocular abnormalities and developmental delay. One patient has been reported with isolated growth hormone deficiency, optic nerve hypoplasia, and a small anterior pituitary in association with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with a compound heterozygous missense mutation in LAMB2 (126).

TBC1D32

TBC1 Domain Family member 32 is thought to be a ciliary protein and a cause of oral facial digital syndrome type IX (127). Two families with biallelic mutations in TBC1D32 and hypopituitarism have been reported (128). For the first family there were two affected siblings and they had panhypopituitarism with an absent anterior pituitary, ectopic posterior pituitary and retinal dystrophy while in a third family the affected proband had anterior pituitary hypoplasia, growth hormone deficiency and developmental delay (128). Facial dysmorphism was present with prominent forehead, low set posteriorly rotated ears, hypertelorism and a flat nasal bridge. Autosomal recessive mutations in another ciliopathy related gene IFT172 have been reported to cause GHD with an ectopic posterior pituitary (129).

MAGEL2 and L1CAM

MAGEL2 and L1CAM mutations have been identified in patients with a combination of hypopituitarism and arthrogryposis (130). MAGEL2 mutations cause Schaaf-Yang syndrome which is similar to Prader-Willi Syndrome with hypotonic, obesity, developmental delay, contractures and dysmorphism. GHD, diabetes insipidus and ACTH deficiency have been reported in 4 patients. In one patient with L1 syndrome due to a L1CAM mutation arthrogryposis was present with GHD.

EIF2S3

EIF2S3 encodes a protein involved in the initiation of protein synthesis with mutations associated with developmental delay and microcephaly. In three patients’ mutations in EIF2S3 have been associated with GHD and central hypothyroidism (131). Inheritance is X-linked.

FOXA2

FOXA2 is a transcription factor involved in pituitary and pancreatic B-cell development and de novo heterozygous mutations cause a phenotype of congenital hypopituitarism with congenital hyperinsulinism (132).

OTHER MUTATIONS

In addition to the above mutations in CDON (133) (nonsense heterozygous), GPR161(134) (homozygous missense) and ROBO1(135) (heterozygous frameshift, nonsense and missense) have been associated with pituitary stalk interruption syndrome.

|

Table 2. Genetic Defects of Pituitary Development and their Phenotype

|

|

Gene

|

Pituitary Deficiencies

|

MRI phenotype

|

Inheritance

|

Other phenotypic features

|

|

ARNT2

|

GH, TSH, ACTH, LH, FSH, ADH

|

Absent PP, ectopic PP, thin stalk, thin corpus callosum, delayed myelination

|

AR

|

Hip dysplasia, hydronephrosis, vesico-ureteric reflux, neuropathic bladder, microcephaly, prominent forehead, deep set eyes, retrognathia

|

|

CDON

|

GH, TSH, ACTH

|

Small anterior pituitary, ectopic posterior pituitary, absent stalk

|

AD

|

|

|

EIF2S3

|

GH, TSH

|

Small anterior pituitary, white matter loss,

|

X-linked recessive

|

Developmental delay and microcephaly, glucose dysregulation (hyperinsulinemia hypoglycemia and post-prandial hyperglycemia)

|

|

GPR161

|

GH, TSH, ADH

|

Small anterior pituitary, ectopic posterior pituitary

|

AR

|

Congenital ptosis, alopecia, syndactyly, nail hypoplasia

|

|

FGFR1

|

GH, TSH, LH, FSH and ACTH

|

Normal or small anterior pituitary, corpus callosum agenesis

|

AD

|

ASD and VSD, brachydactyly, brachycephaly, preauricular skin tags, ocular abnormalities, seizures

|

|

FGF8

|

GH, TSH, ACTH, ADH

|

Absent corpus callosum, optic nerve hypoplasia

|

AD or AR

|

Holoprosencephaly, Moebius syndrome, craniofacial defects, high arched palate, maxillary hypoplasia, microcephaly, spastic diplegia

|

|

FOXA2

|

GH, TSH, ACTH

|

Small shallow sella turcica, anterior pituitary hypoplasia, absent stalk

|

AR

|

Congenital hyperinsulinism

|

|

GLI2

|

GH, TSH and ACTH with variable gonadotrophin deficiency

|

Anterior pituitary hypoplasia

|

AD

|

Holoprosencephaly, cleft lip and palate, anophthalmia, postaxial polydactyly, imperforate anus, laryngeal cleft, renal agenesis

|

|

GLI3

|

GH, TSH, LH, FSH, ACTH

|

Anterior pituitary hypoplasia

|

AD

|

Pallister-Hall syndrome Postaxial polydactyly, hamartoblastoma

|

|

HESX1

|

Isolated GHD through to panhypopituitarism with TSH, LH, FSH, ACTH, prolactin and ADH deficiency

|

Optic nerve hypoplasia, absence of the septum pellucidum, ectopic posterior pituitary, anterior pituitary hypoplasia

|

AR and AD

|

Developmental delay

|

|

IFT172

|

GHD

|

Ectopic posterior pituitary, anterior pituitary hypoplasia

|

AR

|

Retinopathy, metaphyseal dysplasia, and hypertension with renal failure

|

|

IGSF1

|

GH (transient/partial), TSH, prolactin

|

Normal in the majority of cases. Frontoparietal hygroma, hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, and small stalk lesion reported.

|

X-linked recessive

|

Macro-orchidism, delay in puberty

|

|

L1CAM

|

GHD

|

Generalized white matter loss and thin corpus callosum

|

X-linked recessive

|

Arthrogryposis, hydrocephalus, VSD, developmental delay, scoliosis, astigmatism

|

|

LAMB2

|

GHD

|

Small anterior pituitary, optic nerve hypoplasia

|

AR

|

Congenital nephrotic syndrome, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, developmental delay

|

|

LHX3

|

GH, TSH, LH, FSH, prolactin

|

Small, normal or enlarged anterior pituitary

|

AR

|

Short neck with limited rotation

|

|

LHX4

|

GH, TSH and ACTH deficiency

|

Small anterior pituitary, ectopic posterior pituitary, cerebellar abnormalities, corpus callosum hypoplasia

|

AD

|

|

|

MAGEL2

|

GHD, ACTH, ADH

|

Small posterior pituitary, thin corpus callosum and optic nerve hypoplasia

|

Heterozygous mutations on paternal allele

|

hypotonia, obesity, developmental delay, contractures and dysmorphism

|

|

OTX2

|

GH, TSH, LH, FSH and ACTH

|

Normal or small AP, pituitary stalk agenesis, ectopic posterior pituitary, Chiari I malformation

|

AR or AD

|

Microcephaly, bilateral anophthalmia, developmental delay, cleft palate

|

|

POU1F1

|

GH, TSH, prolactin

|

Small or normally sized anterior pituitary

|

AR and AD

|

|

|

PROKR2

|

GH, TSH, ACTH

|

Hypoplastic corpus callosum, normal or small anterior pituitary

|

AD

|

Club foot, syrinx spinal cord, microcephaly, epilepsy

|

|

PROP1

|

GH, TSH, LH, FSH, prolactin, evolving ACTH deficiency

|

Small, normal or enlarged anterior pituitary – may evolve over time

|

AR

|

|

|

RAX

|

GH, TSH, LH, FSH, ACTH, ADH

|

Absent sella turcica and pituitary

|

AR

|

Anophthalmia, bilateral cleft lip and palate

|

|

ROBO1

|

GH, TSH

|

Small or absent anterior pituitary, ectopic or absent posterior pituitary, interrupted or absent stalk

|

AD

|

Strabismus, ptosis

|

|

SOX3

|

GH, TSH, LH, FSH, ACTH. Most commonly isolated GHD

|

Anterior pituitary and infundibular hypoplasia, ectopic posterior pituitary, corpus callosum abnormalities including cysts

|

X-linked recessive

|

Learning difficulties

|

|

SOX2

|

LH, FSH variable GH deficiency

|

Anterior pituitary hypoplasia, optic nerve hypoplasia, septo-optic dysplasia, hypothalamic hamartoma

|

AR

|

Microphthalmia, anophthalmia, micropenis, sensorineural deafness, gastro-intestinal tract defects.

|

|

TBC1D32

|

Isolated GHD to panhypopituitarism

|

Absent or hypoplastic anterior pituitary, ectopic posterior pituitary

|

AR

|

Retinal dystrophy, developmental delay, facial dysmorphism (prominent forehead, low set posteriorly rotated ears, hypertelorism and a flat nasal bridge).

|

|

TCFL7

|

GH

|

Absent posterior pituitary, anterior pituitary hypoplasia, optic nerve hypoplasia, parital agenesis of corpus callosum, thin anterior commissure

|

AD

|

|

Bioinactive GH

Short stature associated with normal to high levels of growth hormone with low serum IGF-I concentrations “bioinactive GH” was first described in 1978 (136). This disorder is associated with a good clinical response to GH therapy and multiple subsequent cases have been reported in the literature (90). These multiple case reports contained no information on the genetic cause of the disorder. The first demonstration of the mechanism responsible for bioinactive GH came in 1997 (137) when Takashi and co-workers described a heterozygous glycine to aspartic acid substitution at amino acid 112 of the GH molecule resulting in impaired binding of the mutant GH to GHR. Reported mutations such as the R77C mutation (138,139) have also been found in normally statured relatives and functional work has failed to identify any difference between wild type and R77C GH on GHR binding, activation of the JAK/STAT pathway, secretion studies or ability to induce cell proliferation (140,141). The clinical scenario of normal to high GH concentrations with low IGF-I levels is not uncommon and a diagnosis of bioinactive GH should not be made unless a mutation is identified where there is a demonstration that the function of the variant GH is impaired.

A homozygous missense mutation (C53S) in the GH1 gene was reported in a Serbian patient with height SDS of -3.6 at 9 years of age (142). Altered affinity for the GH receptor was demonstrated in functional studies, presumably due to alteration of the disulphide bond between Cys-53 and Cys-65 in the GH molecule.

Laron Syndrome

Laron syndrome, caused by loss of function mutations in the GHR gene(143), was first described in 1966 (144). Since then more than 250 patients have been described in the literature with over 70 missense, nonsense, indels and splice mutations within the GHR gene (145). The majority of mutations describe are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner but autosomal dominant inheritance has been described in a small number of cases (146). Patients present with severe short stature having been born with normal birth size. The facial phenotype is similar to severe GH deficiency with frontal bossing and midface hypoplasia. Intellect, development and head circumference are normal. IGF-I, IGFBP-3 and ALS concentrations are low in serum with normal to raised baseline GH levels with raised peak stimulated GH level. Typical adult height is around -5 SD. Measurement of GHBP in serum is useful as, when markedly low, indicates absence of the extracellular component of the GHR. Since mutations can occur in the transmembrane or intracellular domains, the presence of GHBP in serum does not exclude a diagnosis of Laron syndrome. The standard diagnostic test is an IGF-I generation test. Specificity of this test is around 77-91% and when applied to a population with low prevalence of GH insensitivity the positive predictive value of the test is likely to be low (147). In addition, there is a limited normative data for the IGF-I generation test. Buckway at al reported the results of IGF-I generation tests in normal subjects and subjects with GH deficiency, Laron syndrome and idiopathic short stature (148). Sensitivity of the IGF-I generation test in this population (who all had the same E180 splice mutation in the GHR, was 77% (the cut off for a normal result on this test was an increase in IGF-I to >15ng/mL post-GH stimulation (149)). Diagnosis of Laron syndrome therefore relies upon integration of clinical and biochemical findings and selecting patients for further genetic studies.

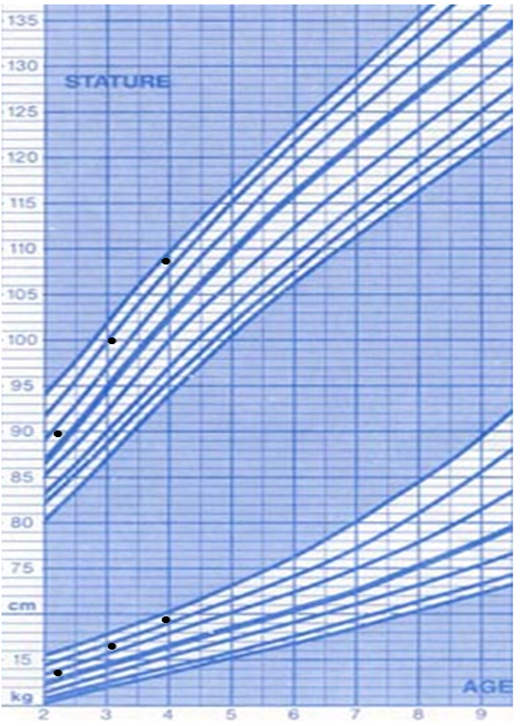

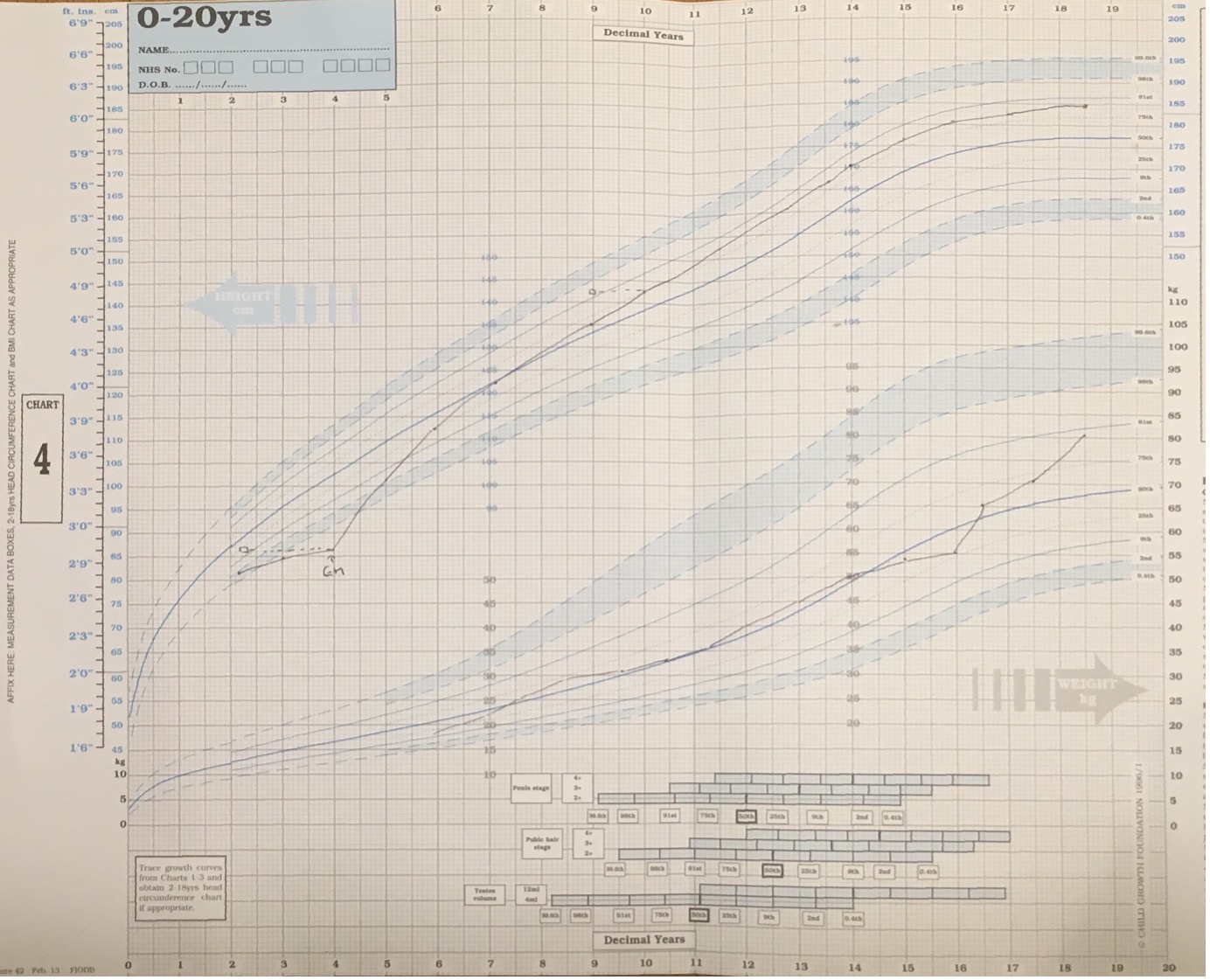

Recombinant human IGF-I therapy provides limited benefit in improving height. In an observational study containing 28 patients with Laron syndrome the results of treatment with 120 mg/kg/day IGF-I for a mean duration of 5 years increased height SDS from -6.1 SD to -5.1 SD (150). In the first year of treatment there was a marked increase in height velocity from 2.8 to 8.7 cm but height velocity markedly decreased after the first year of treatment. In a separate report of 21 individuals with GH insensitivity – 5 of whom had Laron syndrome there was an increase in height SDS from baseline of +1.9 SD with treatment of 120 mcg/kg/day IGF-I for a mean of 10.5 years (151). The treatment effect is markedly lower than that of GH in children with severe congenital GH deficiency (an example of a growth chart of a child with Laron syndrome treated with IGF-I is given in Figure 6). While GH therapy stimulates both hepatic and local IGF-I production, subcutaneous injections of IGF-I do not simulate this local IGF-I production. In addition, GH therapy normalizes not only IGF-I levels but levels of IGFBP-3 and ALS whereas in GH insensitive subjects treated with IGF-I there is no increase in IGFBP-3 or ALS concentrations. Thus, it would be expected that the injected IGF-I would have a much lower half life than endogenous IGF-I. A combined therapy of IGF-I with IGFBP-3 disappointingly was less effective in improving height (152).

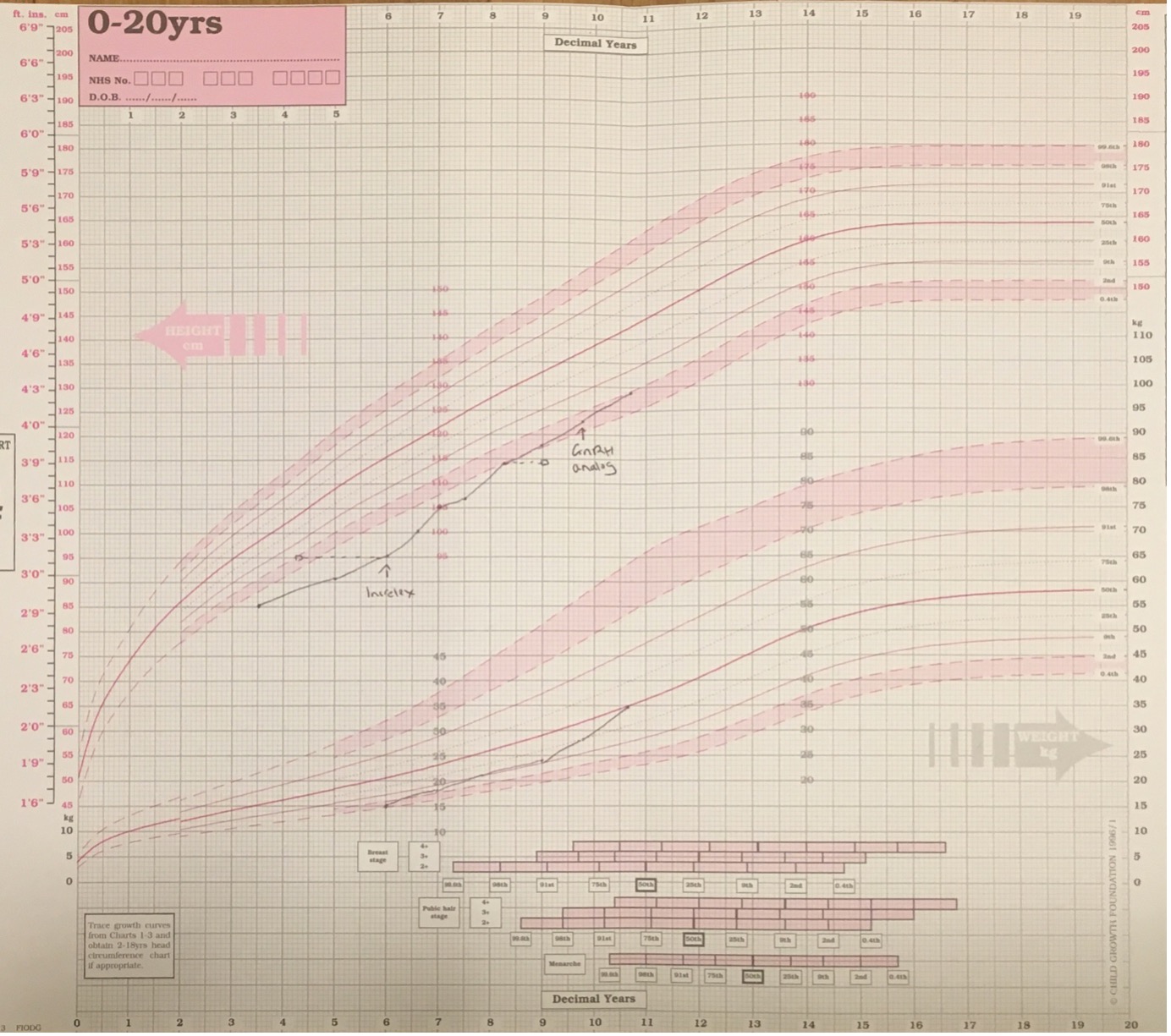

Figure 6. Growth chart of girl with Laron syndrome treated with recombinant human IGF-I (Increlex) from age of 5.8 years when height SDS was -4.2 SD. There is an increase in height velocity over the first year of treatment which is reduced in subsequent years of therapy. Height SDS improves to -2.1 SD by 10.25 years but this has been associated with the onset of puberty at 9 years (treatment with the GnRH analogue Zoladex was introduced at 9.8 years). Current height lies within parental target range. M denotes maternal height and F denotes adjusted paternal height.

STAT5b Mutations

The signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) family contains seven proteins (STAT1, -2, -3, -4, -5a, -5b and -6). Mutations in STAT1(153) and STAT3 are associated with immune deficiency and a mutation in STAT5b was described in a patient with growth hormone insensitivity and immune deficiency (154). The initial report was of a homozygous missense mutation in exon 15, encoding the critical SH2 domain leading to aberrant folding and aggregation of the protein. Six other mutations have been described including a nonsense mutation in exon 5 (155), two distinct nucleotide insertions (156,157) in exons 9 and 10 containing the DNA binding domain, a missense variant within the SH2 domain (158), a four nucleotide deletion in exon 5 (159) and a single nucleotide deletion in the Linker domain (160).

Until recently all the mutations identified were homozygous and the disorder is predominantly inherited in an autosomal recessive manner but dominant negative mutations have now been reported (161). There is some evidence of a mild effect of the heterozygous state as height SDS in parents of affected children is consistently below mean height for the population with range from -0.3 SD to -2.8 SD. Birth weight appears to be within normal limits but postnatal height is severely impaired with height SDS range of -3 to -9.9 (158). Growth is comparable to children with Laron syndrome. Bone age and puberty is commonly delayed perhaps reflecting in part the chronic state of ill health. A prominent forehead, depressed nasal bridge and high-pitched voice are seen in some patients. The biochemical findings are compatible with growth hormone insensitivity with normal to high basal growth hormone concentrations and a raised stimulated peak GH level. Of note, 1 subject had a low stimulated peak GH concentration of 6.6 mcg/. Serum IGF-I, IGFBP-3 and ALS concentrations were consistently low in all subjects, remaining low at end of an IGF-I stimulation test.

Clinical differentiation of patients with STAT5b mutations form those with Laron syndrome can be made with the immunodeficiency. All but one of the reported cases has presented with chronic pulmonary disease, particularly lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, with the other child having severe hemorrhagic varicella. Two patients have died from their lung disease and a further patient has required lung transplantation. Patients with STAT5b mutations also have raised serum prolactin levels which can also be helpful with diagnosis.

Acid Labile Subunit Deficiency

The human IGFALS gene is located on chromosome 16p13.3 and ALS deficiency is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern with homozygous and compound heterozygous mutations identified including missense, nonsense, deletions, duplications and insertions. The mutations are spread throughout the IGFALS gene which contains 2 exons and encodes a protein of 605 amino acids (162). The majority of the mutations are located in the 20 central leucine rich domains. The clinical phenotype, first described in 2004 (163), is of very low serum concentrations of IGF-I, IGFBP-3 and ALS with a moderate degree of short stature (-2 to -3SD).

Limited data is available on size at birth but weight appears to be within the lower half of the normal range (-0.2 to -1.9 SD) with only one individual reported to be SGA with a birth weight of -2.2 SD. The data on birth length is even more limited but all individuals measured were within normal range at -1.5 to +1.0 SD. Data on height during childhood is more abundant and hemorrhagic it is clear that postnatal growth is affected in the majority of individuals carrying ALS mutations. Mean prepubertal height in 17 patients was reported as -2.61 SD (range -3.9 to -1.06 SD) with final adult height of -2.15 SD (range -0.5 to -4.2 SD). There is a preponderance of males in the literature (88% reported cases) which may represent the increased likelihood of males with short stature to present to health care providers. In male’s pubertal onset is commonly delayed (6/11 with onset puberty >14 years and 3/11 onset >15 years). Serum IGF-I and IGFBP-3 standard deviation scores are very low (-3.3 to -11.2 SD for IGF-I and -3.6 to -18.5 for IGFBP-3), with undetectable ALS concentrations in all but one case (164). Levels of GH are increased with a mean peak GH of 46µg/L.

The relatively modest growth impairment in ALS deficiency is likely to be due to the preservation of the local production and action of IGF-I with deficiency of hepatic derived IGF-I. The diagnosis should be suggested by the presence of very low concentrations of IGF-I and, in particular, IGFBP-3 in the presence of moderate growth impairment. Although measurement of ALS is not routinely available this would also be a useful diagnostic tool.

Response to treatment with GH therapy has been poor and one child treated with recombinant human IGF-I did not improve height after 1 year of treatment.

IGF-I Gene Mutations

Deletions and mutations within the IGF1 gene are an extremely rare cause of GH insensitivity. The first patient was reported in 1996 (3) and there have been four subsequent affected families reported (165-168). The first patient described had a homozygous deletion of exons 3 and 5 of the IGF1 gene leading to frameshift and generation of a premature termination codon. He had undetectable levels of serum IGF-I with normal concentrations of IGFBP-3 and ALS with raised baseline and spontaneous GH peak levels. He was born small for gestational age at 1.4 kg at term and displayed profound post-natal growth impairment with sensorineural hearing loss, microcephaly and developmental delay.

One subsequent report identified a similar phenotype of growth impairment, developmental delay, microcephaly and hearing impairment with a homozygous missense variant in exon 6 of IGF-1(167). The patient also had low IGF-I concentrations and high GH levels. Subsequent studies have identified this variant in individuals with normal height and there may be an alternative cause for this child’s growth impairment.