ABSTRACT

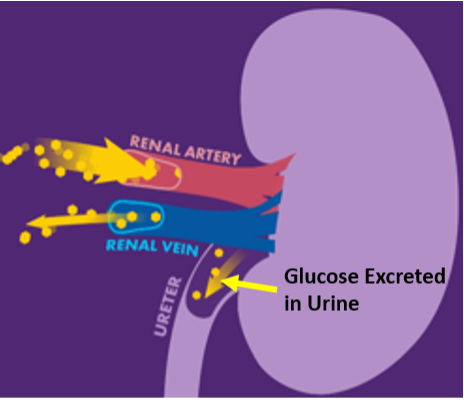

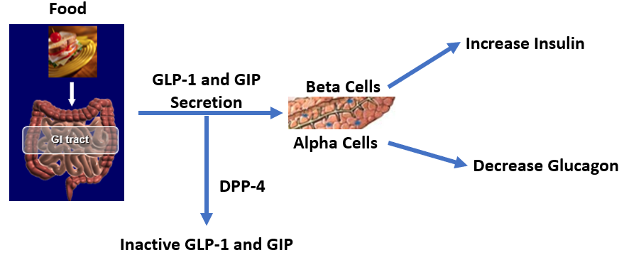

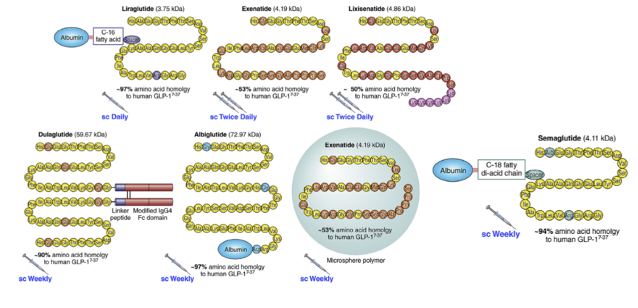

While lifestyle changes such as dietary modification and increased physical activity can be very effective in improving glycemic control, over the long-term most individuals with Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) will require medications to achieve and maintain glycemic control. The purpose of this chapter is to provide the healthcare practitioner with an overview of the existing oral and injectable (non-insulin) pharmacological options available for the treatment of patients with T2DM. Currently, there are ten classes of orally available pharmacological agents to treat T2DM: 1) sulfonylureas, 2) meglitinides, 3) metformin (a biguanide), 4) thiazolidinediones (TZDs), 5) alpha glucosidase inhibitors, 6) dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-4) inhibitors, 7) bile acid sequestrants, 8) dopamine agonists, 9) sodium-glucose transport protein 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and 10) oral glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. In addition, glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, dual GLP-1 receptor and GIP receptor agonists, and pramlintide can be administered by injection. Medications from these distinct classes of pharmaceutical agents may be used as treatment by themselves (monotherapy) or in a combination of 2 or more drugs from multiple classes with different mechanisms of action. A variety of fixed combinations of 2 agents are available in the US and in many other countries. In this chapter we discuss the administration, mechanism of action, effect on glycemic control, other benefits, side effects, and the contraindications of the use of these glucose lowering drugs.

INTRODUCTION

While lifestyle changes such as dietary modification and increased physical activity can be very effective in improving glycemic control, over the long-term most individuals with Type 2 diabetes (T2DM ) will require medications to achieve and maintain glycemic control (1). The purpose of this chapter is to provide the healthcare practitioner with detailed information on the existing oral and injectable (non-insulin) pharmacological options available for the treatment of patients with T2DM. The use of these drugs to treat diabetes during pregnancy, in children and adolescents, and for the prevention of diabetes are discussed in other Endotext chapters (2-4). For information on the management of T2DM and selecting amongst the available pharmacological agents see the chapter by Emily Schroeder in Endotext (5).

Currently, there are ten classes of orally available pharmacological agents to treat T2DM: 1) sulfonylureas, 2) meglitinides, 3) metformin (a biguanide), 4) thiazolidinediones (TZDs), 5) alpha glucosidase inhibitors, 6) dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-4) inhibitors, 7) bile acid sequestrants, 8) dopamine agonists, 9) sodium-glucose transport protein 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and 10) oral glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (Table 1) (6-8). In addition, glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, dual GLP-1 receptor and GIP receptor agonists, and pramlintide can be administered by injection (Table 2) (6-8).

|

Table 1. Currently Available (USA) Oral Hypoglycemic Drugs to Treat Type 2 Diabetes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

General Class Compound/Brand Name |

Generic Available |

Dose Range |

Cost |

|

1st Generation Sulfonylureas |

|||

|

Chlorpropamide/ Diabinese |

Yes |

100-750mg qd |

Low |

|

Tolazamide/ Tolinase |

Yes |

100mg qd to 500mg bid |

Low |

|

Tolbutamide/ Orinase |

Yes |

500mg qd to 1000mg tid with meals |

Low |

|

Acetohexamide/ Dymelor |

Yes |

250mg qd to 750mg bid |

Low |

|

2nd Generation Sulfonylureas |

|||

|

Glyburide (Glibenclamide)/ Diabeta, Glynase |

Yes |

2.5mg qd to 10mg bid |

Low |

|

Glipizide/ Glucotrol, Glucotrol XL |

Yes |

2.5mg qd to 20mg bid |

Low |

|

Glimepiride/ Amaryl |

Yes |

0.5mg to 8mg qd |

Low |

|

Gliclazide/ Diamicron |

Yes |

40mg qd to 160mg bid |

Low |

|

Meglitinides |

|||

|

Repaglinide/ Prandin |

Yes |

0.5mg to 4 mg with meals. Max 16mg/day |

Low |

|

Nateglinide/ Starlix |

Yes |

60-120mg tid with meals |

Low |

|

Biguanide |

|||

|

Metformin/ Glucophage, Glucophage XR |

Yes |

500-2500mg qd or tid depending upon preparation |

Low |

|

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) |

|||

|

Rosiglitazone/ Avandia |

Yes |

4-8mg qd |

High |

|

Pioglitazone/ Actos |

Yes |

15-45mg qd |

Low |

|

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors |

|||

|

Acarbose/ Precose |

Yes |

25-100mg tid with meals |

Low |

|

Miglitol/ Glyset |

Yes |

25-100mg tid with meals |

High |

|

Voglibose/ Basen, Voglib |

Yes |

0.2mg tid with meals |

|

|

Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-4) inhibitors |

|||

|

Alogliptin/ Nesina |

Yes |

25mg qd |

High |

|

Linagliptin/ Tradjenta |

No |

5mg qd |

High |

|

Sitagliptin/ Januvia |

No |

25-100mg qd |

High |

|

Saxagliptin/ Onglyza |

No |

2.5-5mg qd |

High |

|

Vildagliptin/ Galvus |

No |

50mg qd |

|

|

Bile Acid Sequestrant |

|||

|

Colesevelam/ Welchol |

No |

1875mg bid or 3.75-gram packet or bar qd |

High |

|

Dopamine Agonist |

|||

|

Bromocriptine/ Cycloset |

No |

0.8 - 4.8mg qAM |

High |

|

Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors |

|||

|

Canagliflozin/ Invokana |

No |

100-300mg qd |

High |

|

Dapagliflozin/ Farxiga |

No |

5-10mg qd |

High |

|

Empagliflozin/ Jardiance |

No |

10-25mg qd |

High |

|

Ertugliflozin/ Stelgatro |

No |

5-15mg qd |

High |

|

Oral glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists |

|||

|

Semaglutide/ Rybelsus |

No |

7-14mg qd |

High |

|

Table 2. Currently Available (USA) Injectable Hypoglycemic Drugs to Treat Type 2 Diabetes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

General Class Compound/Brand Name |

Generic Available |

Dose Range |

Cost |

|

GLP-1 Receptor Agonist |

|||

|

Exenatide/ Byetta |

No |

5-10mcg bid |

High |

|

Exenatide/ Bydureon |

No |

2mg once weekly |

High |

|

Liraglutide/ Victoza |

No |

0.6-1.8mg qd** |

High |

|

Albiglutide/ Tanzeum* |

No |

30-50mg once weekly |

High |

|

Dulaglutide/ Trulicity |

No |

0.75-4.5mg once weekly |

High |

|

Lixisenatide/ Adlyxin |

No |

10-20mcg qd |

High |

|

Semaglutide/ Ozempic |

No |

0.25-2.0mg once weekly |

High |

|

Dual GLP-1 Receptor/GIP Receptor Agonists |

|||

|

Tirzepatide/ Mounjaro |

No |

5mg-15mg once weekly |

High |

|

Amylin Mimetic |

|||

|

Pramlintide/ Symlin |

No |

15-120mcg tid with meals |

High |

*Withdrawn from market

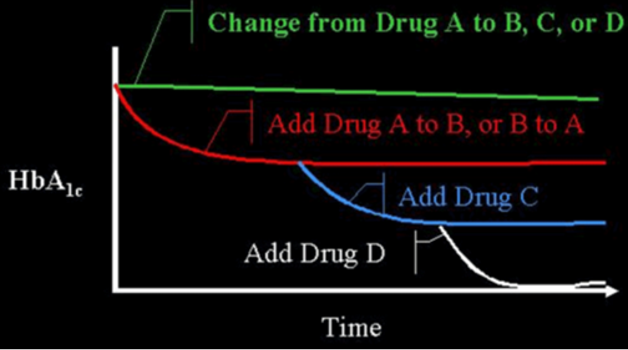

Medications from these distinct classes of pharmaceutical agents may be used as treatment by themselves (monotherapy) or in a combination of 2 or more drugs from multiple classes with different mechanisms of action (6-8). A variety of fixed combination of 2 agents are available in the US and in many other countries (examples shown in Table 3). There are even combinations that contains 3 drugs (Qternmet XR which contains dapagliflozin, saxagliptin, and metformin and Trijardy XR which contains empagliflozin, linagliptin, and metformin). Additionally, there are combinations of GLP-1 receptor agonists and insulin (Table 3). These combination products may be useful and attractive to the patient, as they provide multiple drugs in a single tablet or injection, offering convenience and increased compliance. In the US, they also enable patients to receive two medications for a single medical insurance co-payment. Most importantly, the addition of a second drug results in an additive improvement in glycemic control. When a patient is on drug A if drug B is added to drug A, there is an improvement in glycemic control. This concept can be extended by the addition of a third drug C, and even a fourth drug D (Figure 1).

|

Table 3. Oral Pharmacological Fixed Combination Therapies to Treat Type 2 Diabetes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Drug 1 |

Drug 2 |

Brand Name |

Generic |

|

Glyburide |

Metformin |

Glucovance (discontinued by manufacturer: generic available) |

Yes |

|

Glipizide |

Metformin |

Metaglip (discontinued by manufacturer; generic available) |

Yes |

|

Glimepiride |

Pioglitazone |

Yes |

|

|

Glimepiride |

Rosiglitazone |

Yes |

|

|

Sitagliptin |

Metformin |

No |

|

|

Saxagliptin |

Metformin |

No |

|

|

Pioglitazone |

Metformin |

ACTOSplus Met; ACTOSplus Met XR |

Yes |

|

Repaglinide |

Metformin |

Yes |

|

|

Rosiglitazone |

Metformin |

Yes |

|

|

Linagliptin |

Metformin |

No |

|

|

Alogliptin |

Metformin |

Yes |

|

|

Alogliptin |

Pioglitazone |

No |

|

|

Canagliflozin |

Metformin |

No |

|

|

Dapagliflozin |

Metformin |

No |

|

|

Dapagliflozin |

Saxagliptin |

Qtern |

No |

|

Empagliflozin |

Linagliptin |

No |

|

|

Empagliflozin |

Metformin |

No |

|

|

Ertugliflozin |

Metformin |

Segluromet |

No |

|

Ertugliflozin |

Sitagliptin |

Steglujan |

No |

|

Lixisenatide |

Glargine Insulin |

Soliqua |

No |

|

Liraglutide |

Degludec Insulin |

Xultophy |

No |

Figure 1. Efficacy When Oral Agents are Used as Add-On Therapy. When a patient is on drug A and they are changed to drug B, C, or D, often no improvement in glucose control will be seen. However, if drug B is added to drug A, there is an improvement. This concept can often be extended by the addition of a third drug (C), or even a fourth drug (D). There is decreasing benefit for each additional drug as the baseline A1c level decreases. Note that there is limited data on the use of 4 drug combinations.

OVERVIEW OF DRUGS

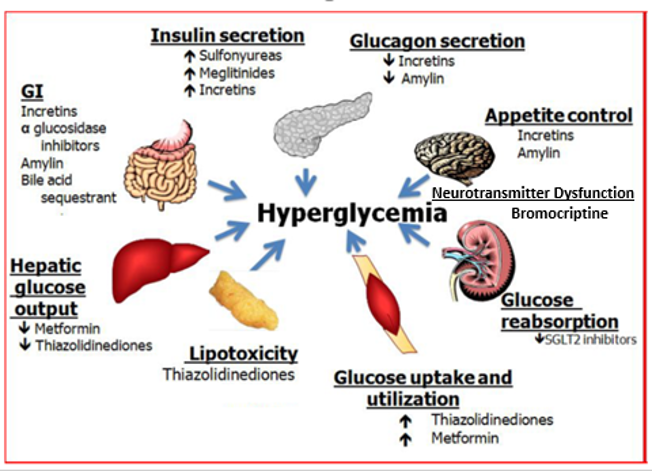

There are a number of different abnormalities that contribute to the hyperglycemia that occurs in patients with T2DM (9). Therefore, the drugs used to treat patients with T2DM can have a number of different mechanisms by which they lower glucose levels. Figure 2 shows the various sites of action of the pharmacological therapies for the treatment of T2DM.

Figure 2. Sites of Action of Pharmacological Therapies for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes.

A broad overview of the most commonly used drugs to treat T2DM is shown in Table 4 and the effect of drugs on blood lipid levels is shown in Table 5.

|

Table 4. Benefits and Side Effects of Commonly Used Drugs |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Drugs |

Ability to Lower Glucose |

Risk of Hypoglycemia |

Weight Change |

Effect on ASCVD |

Effect on Heart Failure |

Effect on Renal Disease |

|

2ndGeneration SU |

High |

Yes |

Increase |

Neutral |

Neutral |

Neutral |

|

Metformin |

High |

No |

Neutral- modest weight loss |

Potential Benefit |

Neutral |

Neutral |

|

TZDs |

High |

No |

Increase |

Potential Benefit (Pioglitazone) |

Increased |

Neutral |

|

DPP-4 inhibitors |

Intermediate |

No |

Neutral |

Neutral |

Potential Increase (saxagliptin and alogliptin) |

Neutral |

|

SGLT2 inhibitors |

Immediate |

No |

Decrease |

Potential Benefit |

Benefit |

Benefit- Reduced progression of renal failure |

|

GLP-1 receptor agonists |

High |

No |

Decrease |

Benefit |

Benefit |

Benefit- Reduced progression of renal failure

|

|

Table 5. Effect of Glucose Lowering Drugs on Lipid Levels* |

|

|---|---|

|

Metformin |

Modestly decrease triglycerides and LDL-C |

|

Sulfonylureas |

No effect |

|

DPP4 inhibitors |

Decrease postprandial triglycerides |

|

GLP1 analogues |

Decrease fasting and postprandial triglycerides |

|

Acarbose |

Decrease postprandial triglycerides |

|

Pioglitazone Rosiglitazone |

Decrease triglycerides and increase HDL-C. Small increase LDL-C but a decrease in small dense LDL |

|

SGLT2 inhibitors |

Small increase in LDL-C and HDL-C |

|

Colesevelam |

Decrease LDL-C. May increase triglycerides |

|

Bromocriptine-QR |

Decrease triglycerides |

|

Insulin |

No effect |

*These effects are beyond benefits of glucose lowering

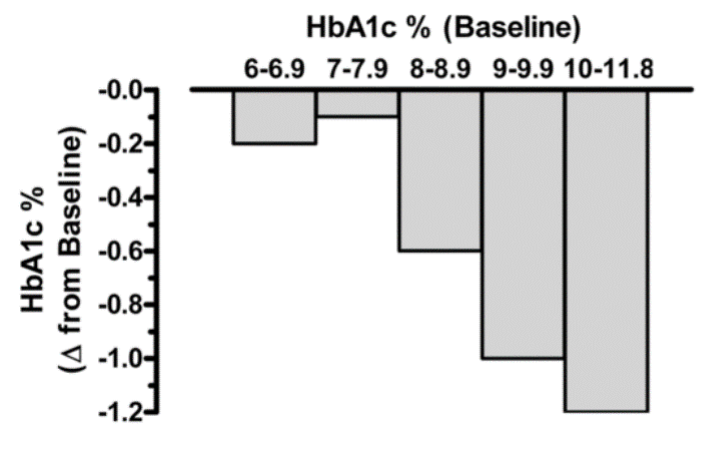

Bloomgarden et al reported results from a meta-regression analysis of 61 clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of the five major classes of oral anti-hyperglycemic agents (10). The results demonstrated that there is a strong direct correlation between baseline A1c level and the magnitude of the decrease in fasting glucose and A1c induced by these drugs (i.e., significantly greater reductions in both fasting plasma glucose and A1c were observed in groups with higher baseline A1c levels). Thus, expectations for the overall magnitude of effect from a given agent might be modest when treating patients whose baseline A1c is <7.5-8.0% while in patients with elevated A1c levels the effect of drug therapy may be more robust (figure 3). A separate meta-analysis of 59 clinical studies reached similar conclusions (11). These results indicate that comparing efficacies among different anti-diabetic medications is challenging, when the baseline HbA1c is different in the studies being compared.

Additionally, the population of patients studied can impact the efficacy of a particular class of drug. For example, patients with limited beta cell function will have a decreased response to sulfonylurea drugs as these agents work via stimulating insulin secretion by the beta cells while TZDs are most effective in patients with insulin resistance. Another example would be the decrease in efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors lowering A1c levels in patients with decreased renal function. A recent trial demonstrated that in individuals with a BMI > 30 pioglitazone reduced HbA1c levels better than sitagliptin while in individuals with a BMI < 30 sitagliptin was more effective (12). In individuals with an eGFR > 90 canagliflozin lowered HbA1c better than sitagliptin while in individuals with an eGFR between 60-90 sitagliptin was more effective (12). These results demonstrate that certain patient characteristics will influence the response to treatment with specific drugs indicating the ability to target drug therapy for the specific patient. Additionally, the variation in response of patients makes it difficult to compare the glucose lowering effects of different hypoglycemic drugs except in direct head-to-head comparison studies.

Figure 3. Relationship between baseline A1c level and the observed reduction in A1c with oral anti-hyperglycemic medications. Irrespective of drug class, the baseline glycemic control markedly influences the overall magnitude of efficacy. Data from Bloomgarden et al, Table 1 (10).

A recent model-based meta-analysis was used to compare glycemic control between a large number of drugs adjusted for important differences between studies, including duration of treatment, baseline A1c, and drug dosages (13). In this analysis 229 studies with 121,914 patients were utilized. Table 6 shows the estimated decrease in A1c levels for different drugs in patients that are drug naïve with an A1c of 8% and a weight of 90kg after 26 weeks of treatment. If one averages the effect on A1c of the highest doses for each drug in a specific drug class the reductions in A1c for each class of drug are metformin 1.09%, sulfonylureas 1.0%, TZDs 0.95%, DPP-4 inhibitors 0.66%, SGLT2 inhibitors 0.83%, and GLP-1 receptor agonists 1.24%. These data and the individual data for each drug in table 6 provides a rough estimate of the efficacy of various drugs and drug classes in lowering A1c levels. One should note that within a drug class there may be differences in the ability of different drugs to lower A1c levels. This is particularly true with the GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs. For additional information there is a website that provides updated comparisons of various agents to treat patients with T2DM (https://www.comparediabetesdrugs.com/). This website shows the effect of glucose lowering drugs on A1c levels, change in weight, and hypoglycemia.

|

Table 6. Estimated Efficacy of Hypoglycemic Drugs Available in US (13) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Drug |

A1c % Decrease |

Drug |

A1c % Decrease |

|

Metformin 2000mg |

1.01 |

Dulaglutide 0.75 |

1.18 |

|

Metformin 2550mg |

1.09 |

Dulaglutide 1.5mg |

1.36 |

|

Glipizide 5-20mg |

0.86 |

Exenatide 10ug BID |

0.86 |

|

Glyburide 1.25-20mg |

1.17 |

Exenatide 2mg QW |

1.16 |

|

Glimepiride 1-8mg |

0.97 |

Exenatide 2mg QWS |

1.14 |

|

Pioglitazone 15mg |

0.62 |

Liraglutide 0.6mg |

0.88 |

|

Pioglitazone 30mg |

0.85 |

Liraglutide 1.2mg |

1.13 |

|

Pioglitazone 45mg |

0.98 |

Liraglutide 1.8mg |

1.25 |

|

Rosiglitazone 4mg |

0.67 |

Lixisenatide 10ug |

0.44 |

|

Rosiglitazone 8mg |

0.91 |

Lixisenatide 20ug |

0.66 |

|

Canagliflozin 100mg |

0.84 |

Semaglutide 0.5mg |

1.43 |

|

Canagliflozin 300mg |

1.01 |

Semaglutide 1.0mg |

1.77 |

|

Dapagliflozin 5mg |

0.65 |

Alogliptin 12.5mg |

0.58 |

|

Dapagliflozin 10mg |

0.73 |

Alogliptin 25mg |

0.66 |

|

Empagliflozin 10mg |

0.69 |

Linagliptin 5mg |

0.59 |

|

Empagliflozin 25mg |

0.77 |

Saxagliptin 2.5mg |

0.59 |

|

Ertugliflozin 5mg |

0.73 |

Saxagliptin 5mg |

0.67 |

|

Ertugliflozin 15mg |

0.81 |

Sitagliptin 100mg |

0.72 |

The decreases in A1c are modeled for drug naïve patients with an A1c of 8% and a weight of 90kg after 26 weeks of treatment.

The Glycemia Reduction Approaches in Diabetes: A Comparative Effectiveness (GRADE) Study randomized approximately 5,000 patients with relatively recent onset of T2DM (4.2 years) on metformin therapy to sulfonylureas, DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, or insulin (14). The primary outcome was the time to primary failure defined as an A1c ≥ 7% over an anticipated mean observation period of 5 years The results as expected demonstrated that the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide was more effective than the sulfonylurea glimepiride and the DPP4 inhibitor sitagliptin in maintaining the A1c < 7% (GLP1 receptor agonist better than sulfonylurea better than DPP-4 inhibitor) (15). Liraglutide and glargine insulin were similarly effective in lowering A1c levels (15). Significantly the majority of patients regardless of drug assignment did not have an A1c level less than 7% (Glargine 67.4%, Glimepiride 72.4%, Liraglutide 68.2%, Sitagliptin 77.4%) demonstrating the progressive nature of diabetes and the difficulty in maintaining good glycemic control. It should be noted that the SGLT2 inhibitors and TZD drugs were not included in this study. The incidences of microvascular complications (renal disease and neuropathy) and death were not different among the four treatment groups (16). There was a suggestion of a decrease in cardiovascular disease in the liraglutide treated group (16,17).

SULFONYLUREAS

Introduction

Sulfonylureas were developed in the 1950s and have been widely used in the treatment of patients with T2DM (18,19). First generation sulfonylureas (acetohexamide, chlorpropamide, tolazamide, and tolbutamide) possess a lower binding affinity for the ATP-sensitive potassium channel, their molecular target (vide infra), and thus require higher doses to achieve efficacy (see table 1) (18,19). These first-generation sulfonylureas are currently rarely used. Subsequently, in the 1980s 2nd generation sulfonylureas including glyburide (glibenclamide), glipizide, gliclazide, and glimepiride were developed and are now widely used (18). The 2nd generation sulfonylureas are much more potent compounds (~100-fold). Sulfonylureas can be used as monotherapy or in combination with any other class of oral diabetic medications except meglitinides because they lower glucose levels by a similar mechanism of action (18,20).

Key characteristics of the different sulfonylureas are shown in Table 7 (18). Of clinical importance is the duration of action, which varies with the rate of hepatic metabolism and the hypoglycemic activity of drug metabolites. Drugs with a long duration of action are more likely to cause severe and prolonged hypoglycemia whereas short acting drugs need to be given multiple times per day (18). Additionally, drugs that are metabolized to active agents (for example glyburide) are also more likely to cause hypoglycemia (18). Most sulfonylureas are metabolized in the liver and are to some extent excreted by the kidney; therefore, hepatic and/or renal impairment increases the risk of hypoglycemia (18).

|

Table 7. Key Characteristics of Sulfonylureas |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Drug |

Duration of action |

Metabolites |

Excretion |

|

Tolbutamide |

6–12 h |

Inactive |

Kidney |

|

Chlorpropamide |

60 h |

Active or unchanged |

Kidney |

|

Tolazamide |

12–24 h |

Inactive |

Kidney |

|

Glipizide |

12–24 h |

Inactive |

Kidney 80% Feces 20% |

|

Glipizide ER |

>24 h |

Inactive |

Kidney 80% Feces 20% |

|

Glyburide |

16–24 h |

Inactive or weakly active |

Kidney 50% |

|

Micronized glyburide |

12-24 h |

Inactive or weakly active |

Kidney 50% Feces 50% |

|

Glimepiride |

24 h |

Inactive or weakly active |

Kidney 60% Feces 40% |

Administration

Sulfonylureas should be taken 30 minutes before meals starting with a low dose with an increase in dosage until desired glycemic control has been achieved. In patients with a high risk of severe hypoglycemia a very low-dose can be the initial therapy while in patients with very high A1c levels one can initiate therapy at a higher dose.

The recommended starting dose of glipizide is 5 mg approximately 30 minutes before breakfast. Geriatric patients or those with liver or renal disease or other risk factors for severe hypoglycemia can be started on 2.5 mg. Patients with very high A1c levels may be started on a higher dose. Based on the glucose response the dose can be increased weekly by 2.5-5 mg. If a once-a-day dose is not satisfactory or the patient requires more than 15 mg per day one can give the drug before breakfast and dinner. The maximum daily dose is 40 mg per day.

The usual starting dose of extended-release glipizide is 5 mg per day with breakfast. Those patients who are at high risk of hypoglycemia may be started at a lower dose. The dose can be increased based on glucose or A1c measurements. The maximum dose is 20 mg per day.

The usual starting dose of glyburide is 2.5 to 5 mg daily with breakfast or the first main meal. Patients at high risk for hypoglycemia should be started on 1.25 mg per day. The dose should be increased weekly by 2.5 mg based on the glucose response. The maximum dose per day is 20 mg.

The usual starting dose of micronized glyburide is 1.5 to 3 mg daily with breakfast or the first main meal. Patients at high risk for hypoglycemia should be started on 0.75 mg per day. The dose should be increased weekly by 1.5 mg based on the glucose response. The maximum dose per day is 12 mg.

The recommended starting dose of glimepiride is 1 or 2 mg once daily. Patients at increased risk for hypoglycemia should be started on 1 mg once daily. The dose should be increased every 1-2 weeks in increments of 1 or 2 mg based upon the patient’s glycemic response. The maximum dose is 8 mg per day.

The recommended starting dose of gliclazide is 40 - 80mg once daily. Patients at increased risk for hypoglycemia should be started on 40 mg once daily. The dose should be increased every 1-2 weeks in increments of 40 or 80 mg based upon the patient’s glycemic response. The maximum dose is 160mg twice a day.

Mechanism of Action

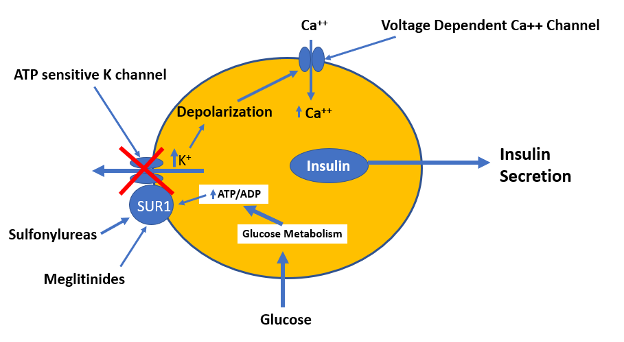

Sulfonylureas are insulin secretagogues and lower blood glucose levels by directly stimulating glucose independent insulin secretion by the pancreatic beta cells (18,20). Through the concerted efforts of GLUT2 (the high Km glucose transporter), glucokinase (the enzyme that phosphorylates glucose), and glucose metabolism, pancreatic beta cells sense blood glucose levels and secrete the appropriate amount of insulin in response (21,22). Glucose metabolism leads to ATP generation and increases the intracellular ratio of ATP/ADP, which results in the closure of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel on the plasma membrane (18,21,23). Closure of this channel depolarizes the membrane and triggers the opening of voltage-sensitive calcium channels, leading to the rapid influx of calcium (18,24). Increased intracellular calcium causes an alteration in the cytoskeleton and stimulates translocation of insulin-containing secretory granules to the plasma membrane and the secretion of insulin (Figure 4) (18).

Figure 4. Mechanism by which glucose, sulfonylureas, and meglitinides stimulate insulin secretion by the beta cells.

The KATP channel is comprised of two subunits, both of which are required for the channel to be functional (24). One subunit contains the cytoplasmic binding sites for both sulfonylureas and ATP, and is designated as the sulfonylurea receptor type 1 (SUR1). The other subunit is the potassium channel, which acts as the pore-forming subunit (24). Either an increase in the ATP/ADP ratio or ligand binding by sulfonylureas or meglitinides to SUR1 results in the closure of the KATP channel and insulin secretion (19,24). Studies comparing sulfonylureas and non-sulfonylurea insulin secretagogues have identified several distinct binding sites on the SUR1 that cause channel closure. Some sites exhibit high affinity for sulfonylureas, while other sites exhibit high affinity for meglitinides.

In addition to binding to SUR1, sulfonylureas also bind to Epac2, a protein activated by cAMP (18). Sulfonylurea-stimulated insulin secretion was reduced both in vitro and in vivo in mice lacking Epac2, indicating that Epac2 also plays a role in sulfonylurea induced insulin secretion (25).

In addition to inducing insulin secretion sulfonylureas have other effects that could play a role in lowering blood glucose levels (18). Specifically, sulfonylureas have been shown to decrease hepatic insulin clearance, inhibit glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha-cells (this may be secondary to increasing insulin secretion), and enhance insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues (this may be partially due to lowering glucose levels and reducing glucotoxicity) (18). The contribution and importance of these additional effects in mediating the glucose lowering effects of sulfonylureas is uncertain.

Glycemic Efficacy

When used at maximally effective doses, results from well-controlled clinical trials have not indicated a marked superiority of one 2nd generation sulfonylurea over another in improving glycemic control (26). Similarly, 2nd generation sulfonylureas exhibit similar clinical efficacy compared to the 1st generation agents (26). Sulfonylureas do not have a linear dose-response relationship and the majority of the A1C reduction occurs at half maximum dosage. The effect of sulfonylureas as monotherapy or when added to metformin therapy on A1c levels varies but typically results in reductions in A1c of approximately 0.50-1.5% (13,19,20,27,28). If A1c levels are very high decreases in the range of 1.5- 2.0% may be seen (19,20,26). Patients with a short duration of diabetes with residual beta cell function (high C-peptide levels) are likely to be most responsive to sulfonylurea therapy (26). Overtime many patients on sulfonylureas require additional therapies (secondary failure). In the ADOPT study, after 5 years 34% of the patients on glyburide monotherapy had fasting glucose levels > 180 mg/dl (i.e., secondary failure) (29). Similarly, in the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), only 34% of patients attained an A1c <7 % at 6 years treated with sulfonylureas (glyburide or chlorpropamide) and this number declined to 24 % at 9 years (18). This lack of durability of sulfonylurea therapy is likely to due to beta cell exhaustion. In addition, the weight gain induced by sulfonylurea therapy may also adversely affect glycemic control.

The results of the GRADE study, which compared glargine insulin, glimepiride, liraglutide, and sitagliptin added to metformin, were discussed earlier in the section entitled “OVERVIEW OF DRUGS”.

Other Effects

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Based on the University Group Diabetes Project (UGDP) sulfonylureas carry a “black box” warning regarding cardiovascular disease (30,31). However, the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group (UKPDS) studied a large number of newly diagnosed patients with T2DM at risk for cardiovascular disease. In this study improved glycemic control with sulfonylureas reduced cardiovascular disease by approximately 16%, which just missed being statistically significant (p=0.052) (32). In the UKPDS, A1c was reduced by approximately 0.9% and the 16% reduction in cardiovascular disease was in the range predicted based on epidemiological studies. Thus, the reduction in cardiovascular events was likely due to improvements in glycemic control and not a direct benefit of sulfonylurea treatment. In support of this conjecture is that in the UKPDS, insulin treatment resulted in a similar decrease in A1c levels and reduction in cardiovascular events (32). Additionally, a large randomized cardiovascular outcome study (Carolina Study) reported that linagliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor, and glimepiride, a sulfonylurea, had similar effects on cardiovascular events (hazard ratio 0.98) (33). Taken together these results suggest that sulfonylureas have a neutral effect on cardiovascular disease.

Side Effects

HYPOGLYCEMIA

The major side effect of sulfonylurea treatment is hypoglycemia, which is more likely to occur and is more severe with long- acting sulfonylureas (18,19). In the UKPDS severe hypoglycemia, defined by need for third-party assistance, occurred each year in 0.4–0.6/100 patients treated with a sulfonylurea while non-severe hypoglycemia was seen in 7.9/100 persons treated with a sulfonylurea (34). Other studies have found even higher rates of severe hypoglycemia with 20–40% of patients receiving sulfonylureas having hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia (requiring third-party assistance) occurring in 1–7% of patients (20,34). With continuous glucose monitoring 30% of well controlled patients with T2DM had episodes of hypoglycemia that were often asymptomatic and nocturnal (35). Of great concern these hypoglycemic events were associated with EKG changes, particularly QTc prolongation (35). Other studies have also observed a very high rate of hypoglycemia in patients with T2DM treated with sulfonylureas when monitored using continuous glucose monitoring (36).

Hypoglycemia typically occurs after periods of fasting or exercise. In light of this hypoglycemic risk, initiation of treatment with sulfonylureas should be at the lowest recommended dose and the dose slowly increased in patients with modestly elevated A1c levels. Older patients (> age 65) and patients with hepatic or renal disease are more likely to experience frequent and severe hypoglycemic reactions, particularly if the goals of therapy aim for inappropriately tight glycemic control (18). Many clinicians avoid the use of long acting sulfonylureas (glyburide) in these high-risk patients as glyburide has a higher risk of hypoglycemia compared to other sulfonylureas (37).

WEIGHT GAIN

In the UKPDS, sulfonylurea treatment caused a net weight gain of approximately 3 kg, which occurred during the first 3-4 years of treatment and then stabilized (19,32). Other studies have similarly observed weight gain with sulfonylurea treatment (26).

FIRST GENERATION SIDE EFFECTS

Chlorpropamide can induce hyponatremia and water retention due to inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) (18). In addition, tolbutamide and chlorpropamide, in certain susceptible individuals, is associated with alcohol-induced flushing (18). Because of an increased risk of side effects 1st generation sulfonylureas are seldom used.

RARE SIDE EFFECTS

Intrahepatic cholestasis and allergic skin reactions, including photosensitivity and erythroderma may rarely occur (Package insert).

Contraindications and Drug Interactions

Sulfonylureas are best avoided in patients with a sulfa allergy who experienced prior severe allergic reactions (Package insert). Otherwise, cross-reactivity between antibacterial and nonantibacterial sulfonamide agents is rare.

In renal failure, the dose of the sulfonylurea agent will require adjustment based on glucose monitoring to avoid hypoglycemia (18). Because it is metabolized primarily in the liver without the formation of active metabolites, glipizide is the preferred sulfonylurea in patients with renal disease (38).

In the elderly, long acting sulfonylureas, such as glyburide, glimepiride and chlorpropamide are not recommended (39).

Sulfonylureas can cause hemolytic anemia in patients with glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency and therefore should be used with caution in such patients (Package insert).

Certain drugs may enhance the glucose-lowering effects of sulfonylureas by inhibition of their hepatic metabolism (antifungals and monoamine oxidase inhibitors), displacing them from binding to plasma proteins (coumarins, NSAIDs, and sulfonamides), or inhibiting their excretion (probenecid) (20).

Summary

While the ability of sulfonylureas to improve glycemic control is robust, the risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain reduce the desirability of this drug class. Additionally, the shorter durability of effectiveness is also a limiting factor. In patients at high risk for the occurrence of severe hypoglycemic reactions or in patients who are obese, using drugs other than sulfonylureas to treat T2DM is indicated if possible. Similarly, in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, or at high risk for cardiovascular disease or renal disease other hypoglycemic drugs have important advantages. Nevertheless, because sulfonylureas are generic drugs and very inexpensive, they continue to be used and play a role in the management of patients with T2DM.

|

Table 8. Summary of the Advantages and Disadvantages of Sulfonylureas |

|

|---|---|

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Inexpensive |

Hypoglycemia |

|

Rapid acting |

Weight gain |

|

Once a day administration possible |

Limited durability |

|

Long history of use |

Need to titrate dose |

MEGLINATIDES

Introduction

The meglitinides are non-sulfonylurea insulin secretagogues characterized by a very rapid onset and abbreviated duration of action (20,40). Repaglinide (Prandin), a benzoic acid derivative introduced in 1998, was the first member of the meglitinide class. Nateglinide (Starlix) is a derivative of the amino acid D-phenylalanine and was introduced to the market in 2001. Unlike sulfonylureas, repaglinide and nateglinide stimulation of insulin secretion is dependent on the presence of glucose (40,41). As glucose levels decrease, insulin secretion decreases, which reduces the risk of hypoglycemia compared with sulfonylureas.

Meglitinides are rapidly absorbed with maximum serum concentrations generally attained within 1 hour and then quickly metabolized by the liver cytochrome CYP3A4 and CYP2C8 pathways, producing inactive metabolites, resulting in a plasma half-life of around 1 h (20). This rapid onset and short duration of action results in the ability of this class of drugs to predominantly reduce postprandial glucose levels (40). Because of the rapid onset and short duration of action meglitinides are given 1-30 minutes prior to meals. The drug should not be administered if the patient is going to skip the meal.

The pharmacokinetics of meglitinides differ with nateglinide having a faster onset and shorter duration of action than repaglinide (41). Nateglinide stimulates early insulin release faster and to a greater extent than repaglinide with insulin levels returning to baseline levels more rapidly (40,41).

Administration

The recommended starting dose of nateglinide is 120 mg three times per day before meals (1-30 minutes). In patients who are near their glycemic goal when treatment is initiated the recommended starting dose of nateglinide is 60 mg three times per day before meals. The maximum dose of nateglinide is 120 mg three times per day before meals.

The recommended starting dose of repaglinide for patients whose A1c is less than 8% is 0.5 mg before each meal (1-30 minutes). For patients whose A1c is 8% or greater the starting dose is 1 or 2 mg orally before each meal. The patient’s dose should be doubled up to 4mg with each meal until satisfactory glycemic control is achieved (should wait one week between increasing dose). The maximum daily dose is 16 mg per day.

Mechanism of Action

Meglitinides bind to a different site on SUR1 in β cells that is separate from the sulfonylurea binding site (Figure 4) (20,40). The effect of meglitinide binding is similar to the effect of sulfonylureas with binding resulting in the closure of the KATP channel leading to cell depolarization and calcium influx resulting in insulin secretion (20,40,41). However, the relatively rapid onset and short duration of action of meglitinides suits their use as prandial glucose-lowering agents (20,40).

Glycemic Efficacy

Studies have shown that A1c reductions are similar to, or slightly less, than those observed with sulfonylurea or metformin treatment when meglitinides are used as monotherapy (20,40). In studies comparing repaglinide monotherapy with sulfonylurea or metformin therapy the decrease in A1c was similar (40,42). In contrast, a study comparing nateglinide with metformin demonstrated that metformin was more effective in lowering A1c levels (43). In a randomized trial comparing repaglinide and nateglinide in patients with T2DM previously treated with diet and exercise, repaglinide was more effective in lowering A1c levels (1.57% vs. 1.04%) (44). While postprandial glucose levels were similar repaglinide was more effective in reducing fasting glucose levels, probably due to its longer duration of action. These clinical findings can be incorporated into clinical decision making. For example, if the main issue for the patient is postprandial hyperglycemia, and fasting glucoses are near normal, an agent, such as nateglinide, that has a limited effect on the fasting glucose would be ideal. However, if one needs reductions in both fasting and postprandial glucose levels a longer acting agent such as repaglinide is a better choice.

Other Effects

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

The Navigator study was a double-blind, randomized clinical trial in 9,306 individuals with impaired glucose tolerance and either cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk factors who received nateglinide (up to 60 mg three times daily) or placebo (45). After 5 years, nateglinide administration did not alter the incidence of cardiovascular outcomes suggesting that meglitinides do not have adverse or beneficial cardiovascular effects. The effect of meglitinides on cardiovascular disease has not been studies in patients with T2DM.

Side Effects

Similar to sulfonylureas, meglitinides can cause hypoglycemia but the risk of severe hypoglycemia is less (20,40,42). The incidence of hypoglycemia is lower with nateglinide than for repaglinide and nateglinide is less likely to cause severe hypoglycemia (20). In one study, the occurrence of symptomatic hypoglycemia was 2% for nateglinide and 7% for repaglinide (41). Weight gain is also a common side effect of meglitinides (approximately 1-3 kg) with nateglinide leading to less weight gain than repaglinide (20,41).

Contraindications and Drug Interactions

Because meglitinides are metabolized by the liver these drugs should be used cautiously in patients with impaired liver function (Package insert).

Drugs that inhibit CYP3A4 (for example ketoconazole, itraconazole and erythromycin) or CYP2C8 (for example trimethoprim, gemfibrozil and montelukast) can result in the increased activity of meglitinides enhancing the risk of hypoglycemia and should be avoided if possible (42).

Summary

Meglitinides can be useful drugs when there is a need to specifically lower postprandial glucose levels (i.e., patients with fasting glucose in desired range but elevated post meal glucose levels). Additionally, because of their short duration of action meglitinides can be useful in patients who eat erratically as this class of drugs can be given only before meals and the duration of action will match the postprandial increase in glucose. The risk of severe hypoglycemia and weight gain is less than sulfonylureas but still must be considered in patients treated with meglitinides. The development of drugs that do not cause weight gain or severe hypoglycemia and lower postprandial glucose levels have resulted in the limited use of meglitinides.

|

Table 9. Summary of the Advantages and Disadvantages of Meglitinides |

|

|---|---|

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Decrease postprandial glucose |

Hypoglycemia |

|

Flexible dosing |

Weight gain |

|

Relatively inexpensive |

Frequent dosing |

|

Short action allowing for missing meals |

Need to titrate dose |

METFORMIN

Introduction

Metformin (Glucophage) is a synthetic analog of the natural product guanidine (20). Since its initial clinical use over 50 years ago, metformin has surpassed the sulfonylureas as the most widely prescribed oral agent for T2DM throughout the world because of its proven efficacy on glycemic control as monotherapy and in combination with many other available agents (20). The widespread acceptance of metformin evolved after the realization that lactic acidosis was not a major problem in individuals with normal renal function. Phenformin, a structural analog of metformin, was previously withdrawn from the market in many countries due its propensity to induce lactic acidosis (20).

Administration

The usual starting dose of metformin is 500 mg twice a day with meals. After 1-2 weeks the dose can be increased to 1500 mg per day (750 mg twice a day or 500 mg in AM and 1000 mg in PM). After another 1-2 weeks the dose can be increased to 1000 mg twice a day. The slow increase in dosage is to reduce GI side effects and the dose should not be increased if GI side effects are occurring. The maximum dose is 2550 mg per day which can be given as 850 mg three times per day with meals but most patients are treated with 1000 mg twice a day with breakfast and dinner.

The usual starting dose of metformin extended release is 500 mg with the evening meal (largest meal). The dose can be increased by 500 mg weekly depending upon tolerability. The maximum dose is 2000 mg with the evening meal.

Note the dose of metformin may need to be adjusted based on renal function (discussed below).

Metformin should be temporarily discontinued when patients are unable to eat or drink. Metformin is seldom used in hospitalized patients.

Mechanism of Action

Metformin decreases hepatic glucose production and improves hepatic insulin sensitivity but has only a modest impact on peripheral insulin-mediated glucose uptake (i.e., insulin resistance), which is likely due to a reduction in hyperglycemia, triglycerides, and free fatty acid levels (46,47). Hyperinsulinemia is reduced and the decrease in hepatic glucose production results in a decrease in fasting glucose levels (20). In addition, metformin also increases intestinal glucose utilization and stimulates GLP-1 secretion (46,47). Insulin secretion is not increased (20). The cellular and molecular mechanisms that account for these changes are not definitively understood.

LIVER

There are several lines of evidence indicating that the liver plays an important role in metformin’s ability to improve glycemic control (46). In humans and rodents, metformin is concentrated in the liver and blocking the uptake of metformin into the liver in mice prevents the ability of metformin to lower blood glucose levels (46,47). As noted above tracer studies in humans show that metformin lowers hepatic glucose production and increases hepatic insulin sensitivity (46). There are a number of proposed mechanisms by which metformin alters hepatic metabolism (46).

- Metformin inhibits mitochondrial ATP production by inhibition of Complex I of the respiratory chain and/or inhibiting mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase, which is required to carry reducing equivalents from the cytoplasm into the mitochondria for re-oxidation (46,47). The decrease in ATP production could decrease hepatic gluconeogenesis (47). This also leads to an increase in AMP.

- Metformin increases hepatic AMP levels and AMP is a potent allosteric inhibitor of fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase, a key enzyme in gluconeogenesis (47). In addition, high AMP levels inhibit adenylate cyclase reducing cyclic AMP formation in response to glucagon, which also decreases glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis (i.e., decreases glucagon activity) (47). The increase in AMP also activates AMP-activated protein kinase.

- Metformin activates AMP-activated protein kinase, which activates catabolic pathways leading to decreased gluconeogenesis, decreased fatty acid synthesis, and increased fatty acid oxidation (46,47). The changes in fatty acid metabolism are thought to account for the improvement in hepatic insulin sensitivity and the decrease in serum triglyceride levels (46).

- Metformin inhibits glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase increasing the cytosolic redox state resulting in a decreased conversion of glycerol and lactate to glucose (48).

INTESTINE

Several lines of evidence indicate that the intestine plays an important role in explaining metformin’s ability to lower blood glucose levels. First, a decrease in hepatic glucose production can only partially account for the decrease in blood glucose (46). Second, in humans with loss-of-function variants in SLC22A1, which decrease the uptake of metformin into the liver, the ability of metformin to lower A1c levels is not impaired (46). Finally, a delayed-release metformin that is retained in the gut, with minimal systemic absorption, is as effective at lowering blood glucose as the standard metformin formulation in patients with T2DM (46,49). There are a number of proposed mechanisms for how the intestine accounts for the beneficial effects of metformin.

- Metformin increases anaerobic glucose metabolism in the intestine resulting in increased intestinal glucose utilization and decreased glucose uptake into the circulation (46). This is likely due to the inhibition of mitochondrial ATP production described above. The increased utilization of glucose by anaerobic metabolism could contribute to metformin induced weight loss.

- Metformin increases GLP-1 secretion, which could increase insulin secretion and decrease glucagon secretion (46). The increase in GLP-1 could also contribute to the weight loss or weight neutral effects of metformin.

- Metformin alters the intestinal microbiome, which could alter glucose metabolism (46,50).

It is clear that there are multiple potential mechanisms by which metformin can improve glucose metabolism and further studies are required to elucidate the relative importance and contribution of these proposed mechanisms and others yet to be identified.

Glycemic Efficacy

Metformin is often used as the initial therapy in patients with diabetes in conjunction with lifestyle changes (6,7). The typical reduction in A1c with metformin therapy is in the range of 1 to 2.0% (20,51). The decrease in A1c induced by metformin is independent of age, weight, and diabetes duration as long as some residual β-cell function remains (20). One retrospective study has reported that African-Americans have a greater decrease in A1c with metformin compared to Caucasians (52). The effect of immediate release and extended release metformin on A1c levels is similar (53). In head-to-head trials, metformin has been shown to produce equivalent reductions in A1c as sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones but is more potent than DPP-4 inhibitors (51).

The durability of glycemic control with metformin is more prolonged than with sulfonylureas but shorter than with TZDs (29). After 5 years of monotherapy, 15% of individuals on rosiglitazone therapy, 21% of individuals on metformin therapy, and 34% of individuals on glyburide (glibenclamide) therapy had fasting glucose levels above the acceptable range (29). The ability to maintain an A1c <7% was 57 months with rosiglitazone, 45 months with metformin, and 33 months with glyburide (glibenclamide) (29).

In addition to the ability to improve glycemic control in monotherapy, metformin in combination with sulfonylureas, meglinitides, TZDs, DPP-4 inhibitors, SGLT-2 inhibitors, insulin, and GLP-1 receptor agonists lowers A1c levels and often allows for patients to achieve their A1c goals (51). As shown in Table 3 there are a large number of combination tablets that include metformin with other glucose lowering drugs.

Hypoglycemia does not occur with metformin monotherapy (51). Hypoglycemia may occur with metformin during concomitant use with other glucose-lowering agents such as sulfonylureas and insulin.

Other Effects

WEIGHT

Metformin is weight neutral or can sometimes result in a modest weight loss (up to 4 kg) (51). When used in combination with sulfonylureas or insulin it blunts the weight gain induced by these agents.

LIPIDS

Metformin decreases serum triglyceride levels and LDL-C levels without altering HDL-C (54,55). In a meta-analysis of 37 trials with 2,891 patients, metformin decreased triglycerides by 11.4mg/dl when compared with control treatment (p=0.003) (54). In an analysis of 24 trials with 1,867 patients, metformin decreased LDL-C by 8.4mg/dl compared to control treatment (p<0.001) (54). In contrast, metformin did not significantly alter HDL-C levels (54). It should be noted that in the Diabetes Prevention Program 3,234 individuals with impaired glucose metabolism were randomized to placebo, intensive lifestyle, or metformin therapy (56). In the metformin therapy group no significant changes were noted in triglyceride, LDL-C, or HDL-C levels compared to the placebo group. Thus, metformin may have small effects on lipid levels.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

In the UKPDS, metformin, while producing a similar improvement in glycemic control as insulin or sulfonylureas, markedly reduced cardiovascular disease by approximately 40% (57). In the ten-year follow-up the patients randomized to metformin in the UKPDS continued to show a reduction in MI and all-cause mortality (58). Two other small randomized controlled trials have also demonstrated cardiovascular benefits with metformin therapy. A study by Kooy et al compared the effect of adding metformin or placebo in overweight or obese patients already on insulin therapy (59). After a mean follow-up of 4.3 years this study observed a reduction in macrovascular events (HR 0.61 CI- 0.40-0.94, p=0.02), which was partially accounted for by metformin’s beneficial effects on weight. In this study the difference in A1c between the metformin and placebo group was only 0.3%. Hong et al randomized non-obese patients with coronary artery disease to glipizide vs. metformin therapy for three years (60). A1c levels were similar, but there was a marked reduction in cardiovascular events in the metformin treated group (HR 0.54 CI 0.30- 0.90, p=0.026). These results suggest that metformin may reduce cardiovascular disease and that this effect is not due to improving glucose control. Metformin decreases weight or prevents weight gain and lowers lipid levels and these or other non-glucose effects may account for the beneficial effects on cardiovascular disease. Larger cardiovascular outcome studies are required to definitively demonstrate a beneficial effect of metformin on cardiovascular disease.

POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME (PCOS)

In patients with PCOS metformin lowers serum androgen levels, increases ovulations, and improves menstrual frequency (61). Metformin may also be associated with weight loss in some women with PCOS (61). Metformin combined with clomiphene may be the best combination in obese women with PCOS to improve fertility (61). For a detailed discussion of the treatment of PCOS see the chapter on polycystic ovary syndrome in Endotext (61).

CANCER

Multiple epidemiological studies have demonstrated an association between metformin treatment and a reduced cancer incidence and mortality (62,63). Treatment with metformin has been associated with a decreased risk of breast, colon, liver, pancreas, prostate, endometrium and lung cancer and marked reductions in cancer-specific mortality for colon, lung and early-stage prostate cancer and improvements in survival for breast, colon, endometrial, ovarian, liver, lung, prostate and pancreatic cancer (62,63). A wide variety of different mechanisms have been proposed that could account for metformin’s anti-tumor effects providing biological plausibility (63). However, data from large randomized controlled trials have not yet definitively demonstrated whether metformin can prevent the development of cancer or is useful in the treatment of cancer (62-65). Further studies are required to elucidate the potential role of metformin in oncology.

Side Effects

GASTROINTESTINAL

The most common side effects of metformin are diarrhea, nausea, and/or abdominal discomfort, which can occur in up to 50% of patients (20,51). These side effects are usually mild and disappear with continued drug administration. The GI side effects are dose-related and slow titration to allow for tolerance can reduce the occurrence of these symptoms (51). Administrating metformin three times a day with meals instead of twice a day may also reduce GI side effects. A small number of patients cannot tolerate the drug, even at low doses (51). Extended-release metformin [metformin XR]) causes fewer GI symptoms and can be used in patients who do not tolerate immediate release metformin (51).

Studies have shown that reduced function of plasma membrane monoamine transporter or organic cation transporter 1 leads to an increase in metformin GI side effects (66,67). Use of drugs that inhibit organic cation transporter 1 activity (including tricyclic antidepressants, citalopram, proton-pump inhibitors, verapamil, diltiazem, doxazosin, spironolactone, clopidogrel, rosiglitazone, quinine, tramadol and codeine) increased intolerance to metformin (66).

LACTIC ACIDOSIS

A very rare complication of metformin therapy is lactic acidosis (51). This complication was much more common with phenformin therapy, the initial biguanide, and the risk with metformin is estimated to be 20 times less (51). The estimated incidence of metformin-associated lactic acidosis is 3–10 per 100,000 person-years (51). This is a potentially lethal complication of metformin therapy that typically occurs when renal dysfunction results in very high blood metformin levels, which inhibit mitochondrial function resulting in the overproduction of lactate (51). In addition to renal disorders other risk factors for metformin associated lactic acidosis include sepsis, cardiogenic shock, hepatic impairment, congestive heart failure, and alcoholism (51). In some circumstances the lactic acidosis observed in patients treated with metformin may not be due to metformin but rather to underlying clinical disorders such as severe sepsis.

VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY

Studies have demonstrated that vitamin B12 malabsorption is a side effect of metformin therapy (51). A randomized controlled trial showed that metformin 850 mg three times per day for over 4 years resulted in a 19% decrease in B12 levels compared to placebo (68). Moreover, 9.9% of patients treated with metformin developed vitamin B12 deficiency (<150 pmol/l) vs. only 2.7% in the placebo group (68). The Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study also demonstrated an increased risk of B12 deficiency with long term metformin use (69). It is now recommended that periodic testing of vitamin B12 levels should be considered in patients on long-term metformin therapy, particularly in the setting of anemia or neuropathy (70).

OVULATION AND PREGNANCY

As discussed above in the polycystic ovary section, treatment of premenopausal women with PCOS with metformin may induce ovulation and thereby result in unplanned pregnancies. In premenopausal anovulatory women started on metformin one needs to discuss the need for contraception.

Contraindications and Drug Interactions

Metformin is contraindicated in patients with advanced kidney or liver disease, acute unstable congestive heart failure, conditions marked by decreased perfusion or hemodynamic instability, major alcohol abuse, or conditions characterized by acidosis (51). Metformin therapy should be suspended during serious illness or surgical procedures. Metformin is seldom used in hospitalized patients.

RENAL DISEASE

A major contraindication to the use of metformin is renal disease (51). Metformin is not metabolized and is excreted intact by the kidneys and therefore kidney function is a major determinant of blood metformin levels. eGFR should be obtained prior to initiating therapy. In patients with renal dysfunction or at risk for developing renal dysfunction eGFR should be obtained more frequently. In patients with a eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 metformin therapy is contraindicated (51). In patients with an eGFR between 30-60mL/min/1.73 m2 metformin can be used but one should consider using lower doses (51). In patients with eGFR < 45mL/min/1.73 m2 the author typically uses ½ the maximal dose of metformin. In patients with labile renal disease, especially if frequent deteriorations in kidney function occur, metformin is best avoided.

IODINATED CONTRAST STUDIES

FDA guidelines indicate that metformin use should be withheld before iodinated contrast procedures if a) the eGFR is 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2, b) in the setting of liver disease, alcoholism, or heart failure, or c) if intra-arterial contrast is used. The eGFR should be checked 48 hours later and metformin restarted if renal function remains stable.

DRUG INTERACTIONS

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, such as topiramate or acetazolamide, can decrease serum bicarbonate levels and induce a non-anion gap, hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. Concomitant use of these drugs with metformin may increase the risk for lactic acidosis (Package Insert).

Certain drugs, such as ranolazine, vandetanib, dolutegravir, and cimetidine, may interfere with common renal tubular transport systems that are involved in the renal elimination of metformin and therefore can increase systemic exposure to metformin and may increase the risk for lactic acidosis (Package Insert).

Summary

Metformin is a commonly used as the first drug for the treatment of diabetes because of excellent efficacy, an outstanding safety profile, low cost, and a long history of use without significant problems.

|

Table 10. Summary of the Advantages and Disadvantages of Metformin |

|

|---|---|

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Inexpensive |

GI side effects |

|

No hypoglycemia |

B12 deficiency |

|

Once a day administration possible |

Lactic acidosis (very rare) |

|

Long history of use |

Need to monitor renal function |

|

No weight gain and maybe weight loss |

|

|

May decrease cardiovascular disease |

|

THIAZOLIDINEDIONES (TZDS)

Introduction

Troglitazone (Rezulin), pioglitazone (Actos), and rosiglitazone (Avandia) are members of the thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of insulin sensitizing compounds that activate PPAR gamma (20,71). Troglitazone was withdrawn from the US, European, and Japanese markets in 2000 due to an idiosyncratic hepatic reaction leading to hepatic failure and death in some patients (20,71). This idiosyncratic hepatic reaction has not occurred with pioglitazone or rosiglitazone (71). TZDs decrease insulin resistance and thereby enhance the biological response to endogenously produced insulin, as well as exogenous insulin (71).

Administration

Initiate pioglitazone at 15 mg or 30 mg once a day with or without food. Use 15 mg in patients where there is concern of fluid retention. If there is inadequate glycemic control, the dose can be increased in 15 mg increments up to a maximum of 45 mg once daily.

Initiate rosiglitazone at 4 mg once a day with or without food. If there is inadequate glycemic control, the dose can be increased to a maximum of 8 mg once daily.

Because the maximum effect of TZDs on glycemic control may take 10-14 weeks one should wait 12 weeks before deciding whether to increase the dose of TZDs.

Mechanism of Action

The primary effect of pioglitazone and rosiglitazone is the reduction of insulin resistance resulting in an improvement of insulin sensitivity (20,71,72). Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are selective agonists for the PPAR gamma receptor, a member of the super-family of nuclear hormone receptors that function as ligand-activated transcription factors (71,72). In the absence of ligand, PPARs bind as hetero-dimers with the 9-cis retinoic acid receptor (RXR) and a multi-component co-repressor complex to a specific response element (PPRE) within the promoter region of their target genes (71,72). Once PPAR gamma is activated by ligand, the co-repressor complex dissociates allowing the PPAR-RXR heterodimer to associate with a multi-component co-activator complex resulting in an increased rate of gene transcription (71,72). Additionally, PPAR gamma can repress target gene expression by negative feedback on other signal transduction pathways, such as the nuclear factor kB (NF-kB) signaling pathway, in a DNA binding independent manner (71). The target genes of PPAR gamma include those involved in the regulation of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism and inflammation (71,72).

PPAR gamma is highly expressed in adipose tissue while its expression in skeletal muscle is low (71,72). In the liver PPAR gamma expression is low but increases in obesity and thus in obese individuals it is possible that TZDs directly affect the liver (73). It is likely that the primary effects of TZDs are on adipose tissue, followed by secondary benefits on other target tissues of insulin (71). TZDs promote fatty acid uptake and storage in adipose tissue resulting in a decrease in circulating fatty acids and a decrease in fat accumulation in liver, muscle, and pancreas leading to the protection of these tissues from the harmful metabolic effects of higher levels of fatty acids (20,71). This decrease in fat accumulation in liver and muscle leads to an improvement in insulin action and the decrease in the pancreas may improve insulin secretion. Additionally, PPAR gamma agonists increase the expression and circulating levels of adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived protein with insulin sensitizing activity (71). A decrease in the gene expression of other adipokines involved in induction of insulin resistance, such as TNF-alpha, resistin, etc. are likely to also contribute to the improvement in insulin resistance that occurs with TZDs (71). Finally, the activation of PPAR gamma in other tissues may contribute to the beneficial effects of TZDs.

Glycemic Efficacy

Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone decrease A1c levels to a similar degree as metformin and sulfonylurea therapy (typically a 1.0-1.5% decrease in A1c) (20,71). The decreases in fasting plasma glucose were observed as early as the second week of therapy but maximal decreases occurred after 10-14 weeks (20,74). This differs from other hypoglycemic drugs where the maximal effect occurs more rapidly. TZDs lower both fasting and postprandial glucose levels (71). TZDs are more effective in improving glycemic control in patients with marked insulin resistance (75).

TZDs are effective in combination with other hypoglycemic drugs including insulin (20,41,74). TZDs do not cause hypoglycemia when used as monotherapy or in combination with metformin (20,41). In combination with insulin or insulin secretagogues, TZDs can potentiate hypoglycemia. If hypoglycemia occurs one needs to adjust the dose of insulin or insulin secretagogues.

The durability of glycemic control with TZDs is more prolonged than with either sulfonylureas or metformin (18). After 5 years of monotherapy, 15% of individuals on rosiglitazone, 21% of individuals on metformin, and 34% of individuals on glyburide (glibenclamide) had fasting glucose levels above the acceptable range (18). The ability to maintain an A1c <7% was 57 months with rosiglitazone, 45 months with metformin, and 33 months with glyburide (glibenclamide) (18). Similar results were observed when pioglitazone therapy was compared to sulfonylurea therapy (76). After 2-years of therapy 47.8% of pioglitazone-treated patients and only 37.0% of sulfonylurea-treated patients maintained an A1c <8%. Studies have shown that TZDs improve and preserve beta cell function, which may account for their better durability (77-79).

Other Beneficial Effects

PROTEINURIA

A meta-analysis of 15 studies (5 with rosiglitazone and 10 with pioglitazone) involving 2,860 patients demonstrated that TZDs decreased urinary albumin excretion in patients without albuminuria, in patients with microalbuminuria, and in patients with proteinuria (80).

BLOOD PRESSURE

TZDs modestly lower BP. In a review of 37 studies TZDs lowered systolic BP by 4.70 mm Hg and diastolic BP by 3.79 mm Hg (81).

LIPIDS

The effect of TZDs on lipids depends on which agent is used. Rosiglitazone increases serum LDL cholesterol levels, increases HDL cholesterol levels, and only decreases serum triglycerides if the baseline triglyceride levels are high [66]. In contrast, pioglitazone has less impact on LDL cholesterol levels, but increases HDL cholesterol levels, and decreases serum triglyceride levels (82). In the PROactive study, a large randomized cardiovascular outcome study, pioglitazone decreased triglyceride levels by approximately 10%, increased HDL-C levels by approximately 10%, and increased LDL-C by 1-4% (83). It should be noted that reductions in the small dense LDL subfraction and an increase in the large buoyant LDL subfraction are seen with both TZDs (82). Treatment with pioglitazone for 12 weeks resulted in a significant increase in the ability of HDL to facilitate the efflux of cholesterol from cells (84).

In a randomized head-to-head trial, it was shown that pioglitazone decreased serum triglyceride levels and increased serum HDL cholesterol levels to a greater degree than rosiglitazone treatment (85,86). Additionally, pioglitazone increased LDL cholesterol levels less than rosiglitazone. In contrast to the differences in lipid parameters, both rosiglitazone and pioglitazone decreased A1c and C-reactive protein to a similar extent. The mechanism by which pioglitazone induces more favorable changes in lipid levels than rosiglitazone is unclear, but differential actions of ligands for nuclear hormone receptors are well described.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Studies with pioglitazone have suggested a beneficial effect on cardiovascular disease. The PROactive study was a randomized controlled trial that examined the effect of pioglitazone vs. placebo over a 3-year period in patients with T2DM and pre-existing macrovascular disease (87). With regard to the primary endpoint (a composite of all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction including silent MI, stroke, acute coronary syndrome, endovascular or surgical intervention in the coronary or leg arteries, and amputation above the ankle), there was a 10% reduction in events in the pioglitazone group but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.095). It should be noted that both leg revascularization and leg amputations are not typical primary end points in cardiovascular disease trials and these could be affected by pioglitazone induced edema. When one focuses on standard cardiovascular disease endpoints, the pioglitazone treated group did demonstrate a 16% reduction in the main secondary endpoint (composite of all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and stroke) that was statistically significant (p=0.027). In the pioglitazone treated group, blood pressure, A1c, triglyceride, and HDL cholesterol levels were all improved compared to the placebo group making it very likely that the mechanism by which pioglitazone decreased vascular events was multifactorial.

The IRIS trial was a multicenter, double-blind trial that randomly assigned 3,876 patients with insulin resistance but without diabetes and a recent ischemic stroke or TIA to treatment with either pioglitazone or placebo (88). After 4.8 years, the primary outcome of fatal or nonfatal stroke or myocardial infarction occurred in 9.0% of the pioglitazone group and 11.8% of the placebo group (hazard ratio 0.76; P=0.007). All components of the primary outcome were reduced in the pioglitazone treated group. Additionally, in the subgroup of patients with “prediabetes” pioglitazone therapy also reduced cardiovascular events (89). Fasting glucose, fasting triglycerides, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure were lower while HDL cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels were higher in the pioglitazone group than in the placebo group. Although this study excluded patients with diabetes the results are consistent with and support the results of a protective effect of pioglitazone observed in the PROactive study.

In contrast to the above results, a study compared the effect of pioglitazone vs. sulfonylurea on cardiovascular disease and did not observe a reduction in events with pioglitazone treatment (TOSCA.IT) (90). Patients with T2DM (n= 3,028), inadequately controlled with metformin monotherapy (2-3 g per day), were randomized to pioglitazone or sulfonylurea and followed for a median of 57 months. Only 11% of the participants had a previous cardiovascular event. The primary outcome was a composite of first occurrence of all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, or urgent coronary revascularization and occurred in 6.8% of the patients treated with pioglitazone and 7.2% of the patients treated with a sulfonylurea (HR 0.96; NS). Limitations of this study are the small number of events likely due to low-risk population studied and the relatively small number of participants. Additionally, 28% of the subjects randomized to pioglitazone prematurely discontinued the medication. Thus, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, it should be noted that when patients in this study were analyzed based on the risk of developing cardiovascular disease those at high risk had a marked reduction in events when treated with pioglitazone compared to the sulfonylurea (91).

Further support for the beneficial effects of pioglitazone on atherosclerosis is provided by studies that have examined the effect of pioglitazone on carotid intima-medial thickness. Both the Chicago and Pioneer studies demonstrated favorable effects on carotid intima-medial thickness in patients treated with pioglitazone compared to patients treated with sulfonylureas (92,93). Additionally, in patients with “prediabetes” pioglitazone also slowed the progression of carotid intima-medial thickness (94). Similarly, Periscope, a study that measured atheroma volume by intravascular ultrasonography, also demonstrated less atherosclerosis in the pioglitazone treated group compared to patients treated with sulfonylureas (95).

There are a large number of potential mechanisms by which pioglitazone might reduce cardiovascular disease (Table 11) (79). In addition to altering risk factors pioglitazone has direct anti-atherogenic effects on the arterial wall that could reduce cardiovascular disease (79).

|

Table 11. Effect of Pioglitazone on Cardiovascular Risk Factors |

|

|---|---|

|

Cardiovascular Risk Factor |

Effect of Pioglitazone |

|

Visceral Obesity |

Decreases |

|

Hypertension |

Lowers BP |

|

High Triglycerides |

Lower TG |

|

Low HDL cholesterol |

Increases HDL cholesterol |

|

Small dense LDL |

Converts small LDL to large LDL |

|

Endothelial dysfunction |

Improves |

|

Hyperglycemia |

Lowers A1c |

|

Inflammation |

Lowers CRP |

|

PAI-1 |

Lower PAI-1 |

|

Insulin resistance |

Reduces |

|

Hyperinsulinemia |

Lowers insulin levels |

While the data from a variety of different types of studies strongly suggests that pioglitazone is anti-atherogenic, the results with rosiglitazone are different. Several meta-analyses of small and short-duration rosiglitazone trials suggested that rosiglitazone was associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes (96,97). However, the final results of the RECORD study, a randomized trial that was specifically designed to compare the effect of rosiglitazone vs. either metformin or sulfonylurea therapy as a second oral drug in those receiving either metformin or a sulfonylurea on cardiovascular events, have been published and did not reveal a difference in cardiovascular disease death, myocardial infarctions, or stroke (98,99). Similarly, an analysis of patients on rosiglitazone in the BARI 2D trial also did not suggest an increase or decrease in cardiovascular events in the patients treated with rosiglitazone (100).

Thus, while the available data indicate that pioglitazone is anti-atherogenic, the data for rosiglitazone suggests a neutral effect. Whether these differences between pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are accounted for by their differential effects on lipid levels or other factors is unknown.

METABOLIC DYSFUNCTION ASSOCIATED STEATOTIC LIVER DISEASE (MASLD) AND METABOLIC DYSFUNCTION ASSOCIATED STEATOHEPATITIS (MASH)

Studies have shown that pioglitazone has beneficial effects on MASLD and MASH (101). In an early study 55 patients with impaired glucose tolerance or T2DM and liver biopsy-confirmed MASH were randomized to pioglitazone 45 mg/day or placebo (102). After 6 months of therapy liver enzymes improved and hepatic fat decreased, measured by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Moreover, histologic findings improved including steatosis (P=0.003), ballooning necrosis (P=0.02), and inflammation (P=0.008). However, fibrosis was unchanged. A more recent study randomized 101 patients with prediabetes or T2DM and biopsy-proven MASH to pioglitazone 45 mg/day or placebo for 18 months (103). The primary outcome was a reduction of at least 2 points in the MASLD activity score in 2 histologic categories without worsening of fibrosis. Pioglitazone treatment resulted in 58% of patients achieving the primary outcome vs. only 17% of the placebo group (p<0.001) and 51% had resolution of MASH compared to 19% of the placebo group (p<0.001). Moreover, pioglitazone treatment improved the fibrosis score.

A meta-analysis of 8 randomized controlled trials (5 using pioglitazone and 3 using rosiglitazone) with 516 patients with biopsy-proven MASH reported that TZD treatment was associated with improved advanced fibrosis (OR, 3.15; P = .01), fibrosis of any stage (OR, 1.66; P = .01), and MASH resolution (OR, 3.22; P < .001) (104). Similar results were observed in patients with and without diabetes. Pioglitazone was more effective in improving MASH than rosiglitazone.

These studies demonstrate that pioglitazone has beneficial effects on MASLD and MASH. Whether this will result in improved clinical outcomes will require additional studies. TZDs are not FDA approved for the treatment of MASLD or MASH.

POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME

TZDs by improving insulin sensitivity decrease circulating androgen levels, improve ovulation rates, and improve glucose tolerance in patients with PCOS (61). Small trials have shown some benefit of TZDs for the treatment of infertility, usually in conjunction with clomiphene (61). Concerns regarding toxicity have limited the use of TZDs for the treatment of PCOS but if a patient has diabetes and TZDs are chosen for treating the diabetes one can anticipate beneficial effects on the PCOS.

Side Effects

WEIGHT GAIN